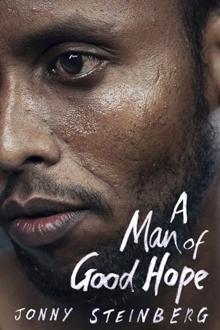

In my review of The Surfacing, I commented that I would have appreciated a little more context of the Franklin expedition. One of the advantages of non-fiction is the potential for setting the human story within a wider sociopolitical framework. From A Man of Good Hope, I’ve come to a slightly better understanding of the importance of lineage and clan to Somali society and the explosion of violence in post-apartheid South Africa against refugees from other parts of Africa, touched on in the novel, Zebra Crossing. Although relatively comfortable living with his wife and child in Addis Ababa, Asad is determined to make it to South Africa, with its reputation for both justice and wealth. It’s a cruel disappointment when, establishing a small shop in a township, he and his fellow Somalis come under repeated attack from their neighbours and customers. Steinberg sees the disturbing xenophobia among his less affluent fellow South Africans as “a product of citizenship, the claiming of a new birthright” (p270).

Even though Asad receives little schooling, he shows the humbling respect for education often found amongst those who can’t take such things for granted. He marries twice, both unlikely unions, the first still in his teens as revenge for an insult that quickly turns to love. I was interested to read about the impact of FGM from the male point of view, in complicating the consummation of the marriage, and, although painful to read about, I would have liked to know more.

Initially I found the inclusion of the author’s context intrusive and a distraction from the main story. But I came to appreciate his gentle reflections on the ethics of his enterprise both from the point of view of Asad’s relative powerlessness and the potential disturbance in having his own distressing experiences reflected back to him in print. (In fact, Asad declined to read the entire book before publication, seeing it more as a commercial transaction.) The book is categorised as biography, but could also be classed as memoir, in its reliance on memory that not only has the potential for unreliability (although backed up by Steinberg’s research) but is influenced by the context in which those memories are produced. For example, when interviewed for possible asylum in America, like the Russian immigrants hoping for reparations in A Replacement Life, he does not tell the whole truth but plays the role the necessary to get where he needs to be:

For the fuel that burned inside him and that made him Asad Hirsi Abdullahi was drained from the story he related … The story he crafted whittled away at the flesh of his being, leaving only a stick figure, hapless refugee (p300)

If he has to do something similar to secure his book deal, at least he has a biographer who is alert to the possibility. In contrast, once settled in America, he shows his appreciation of his good fortune with classic immigrant zeal, perhaps most movingly manifest around the birth of his daughter:

there is a whole machine in this city waiting for the ladies to go into labour. You pick up the phone and it comes to you. Before I had hung up, I said to myself: When I get a job, I want to pay taxes in this country.

… Where is home? Somalia? I cannot even go to Somalia. How can you call a place you cannot go to “home”? Home is where the social security is, brother. Home is where the social workers knock on the door because they do not want you to kill your baby by mistake. (p318)

His gratitude for a welfare system which some recipients might consider interfering, is particularly poignant given that this was a significant gap in his own childhood.

Thanks to Jonathan Cape for my review copy. It’s been a positive experience for me to read and review some non-fiction, although I’ll be back to fiction with my next post with a double review of two novels about families.

Meanwhile, allow me to share my short story on the refugee experience, Elementary Mechanics and my response to Charli Mills’ latest flash fiction challenge on a moment of being, my far from adequate homage to Asad and others like him:

They came for mobile top-ups and single cigarettes. When times were hard, we slipped them something extra. They were our neighbours; how could we not trust them?

They came with guns and machetes. They seized our stock and smashed or burned what they could not carry. We were foreigners; how could they bear to let us take their money?

They came once more with smiles but no apologies. The next shop was three hours’ walk away; how could they do without us?

We stood at the counter, sweating, shaking. No, we said, this is not how life should be.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed