The perspective on corruption is chilling, to quote one of the minor characters, Lou, the moral voice of the novel (p234-5):

My apologies if that sounds preachy; the novel as a whole is much more subtle in its approach and all the more effective for that. And, while a serious novel, it’s not without humour, as in the legacy of following a previous marketing consultant’s advice too closely in the bank’s headquarters (p56-57):

‘All our meeting rooms are named after countries,’ Berkshire says as the lift silently makes its way up and up and up. ‘Reminds everyone that we’re global. That they’re part of something bigger.’

‘Good idea,’ says Baxter.

‘No, not really. Just makes everyone want to go on holiday. Amazing how many people actually go on holiday to the same place as the meeting room they spend most of their time in …’

Yet, even in the hospital, when he clearly despises his former self, James still perceives relationships through the advertising executive’s prism, mentally segmenting the staff and patients in terms of what he might sell them.

I found James’ psychotic experiences extremely convincing, articulating the physical, as well as the mental, torment which is often overlooked. There was also a clever, if slightly concrete, illustration of the defence of projection of the unwanted parts of ourselves in his use of the toy animals and figurines. His depiction of the hospital ward also, sadly, rings true, especially that the relationships patients have with each other are more significant than any of them might have with the staff, and the importance of adhering to the unwritten rules (p61):

Get dressed. Dressing gown and pyjamas are the costume of the unwell. We are not unwell, we are just in here, working towards getting back out there. Getting dressed, being involved, will get you noticed by them and can help reduce your stay. Moping around in your nightwear will only help convince them you’re in here for the long haul.

… They like us placid. So placid we are. Not that they trust us to be placid of our own volition of course. They fill us full of pills and potions that turn us into the walking dead to ensure that we are placid.

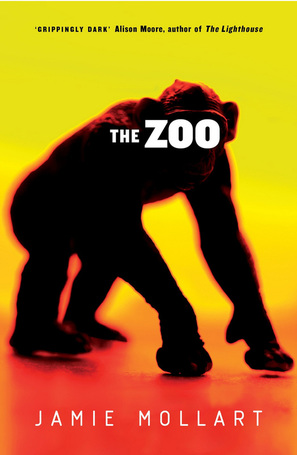

I did wonder, however, from the references to ‘orderlies’ and doctors in white coats, in what kind of hospital the author had done his research. But that’s a minor criticism of a powerful debut novel, and it’s testament to Jamie Mollart’s writing that I’m able to produce a (hopefully half-decent) review almost a month after I finished reading it.

I knew that Jamie was a fellow East Midlands writer and member of Nottingham Writers’ Studio when I read his novel, but I wrote this review before meeting him for the first time at the library event last week. It was an honour to share a platform with him and a pleasure to hear him read from his first chapter. I only wish I’d got a photo of the moment we realised we’d both brought along a copy of the other’s novel to be signed – another wonderful first for me!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed