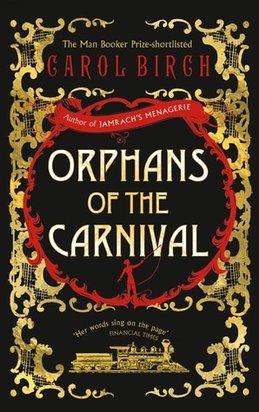

Based on the true story of a 19th-century stage performer, Orphans of the Carnival explores both the downside of celebrity – “gazed [at] so much they hadn’t really seen her at all” (p127) – and the isolation of being different, when “everyone loved her because she made them so glad they were themselves and not her” (p122). So accustomed to being one-of-a-kind she rejects her manager’s (and husband-to-be’s) insinuation of a common thread between his experience and hers, when he says “If it was possible to die of ridicule, I would have died in childhood” (p144).

I would have liked the author to have made more of these psychological themes but, although we are never in doubt of her extreme vulnerability (alternatingly praised and pilloried by the press, dependent on her various managers for her physical safety and, apart from her stage appearances, not daring to appear in public unless veiled), until her tragic death, the novel doesn’t have as much jeopardy as I’d have liked. That might partly explain the author’s decision to interrupt Julia’s story at intervals with that of 1980s South Londoner Rose, a rather irritating character who attributes consciousness to objects and fills her flat with bric-a-brac salvaged from skips. But Rose’s eccentricity serves to highlight another disturbing angle on difference, and the display of human remains, when the two accounts finally intersect.

Carol Birch’s eleventh novel touches on identity, acceptance and the search for independence through her portrayal of the career of an unusual and intriguing young woman. Thanks to Canongate for my review copy.

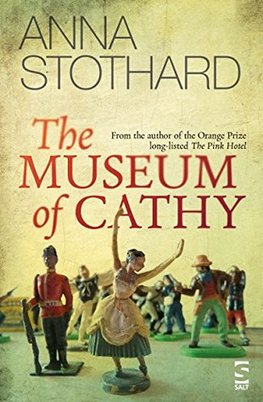

When Cathy receives a Kissing Beetle – so-called because of their habit of biting sleeping humans in the soft tissue around the lips and eyes – preserved in resin that morning in the post, she knows that Daniel is once more on her trail. He’s sent her other objects while he’s been in prison, all of which she’s kept, but she hasn’t heard from him for over four years. She lived with him in a dilapidated holiday chalet on the Essex coast from the age of nineteen until she fled in the night a few years later. Nice-guy Tom knows nothing about him.

Cathy’s attachment to the flotsam and jetsam of her past reminded me of the objectmemories in Anna Smaill’s novel, The Chimes. For Cathy, keeping these objects in order is a form of control. As the novel progresses, we understand more of her past disorder, not only her lonely feral childhood with neglectful parents but her friendship with Daniel’s younger brother, Jack, some of whose treasures are now in her collection. Daniel also seeks control, perhaps at Cathy’s expense.

When Daniel turns up at the museum party, Cathy can’t resist taking him upstairs to her office where they can talk in private. While I know that victims of domestic violence often return to their abusers, and this reckless behaviour did make sense as more of Cathy’s character emerged, I wasn’t so convinced when the plot spirited her away from the safety of the party. But it did ratchet up the tension as the couple review their relationship and the unspoken grief that binds them together.

Overall, I found Anna Stothard’s fourth novel to be an engaging and thought-provoking exploration of memory, guilt, abuse and the attempt to control the uncontrollable. Thanks to Salt for my review copy.

For more musings and links on fictional museums and collectables, see my review of The Lost Time Accidents.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed