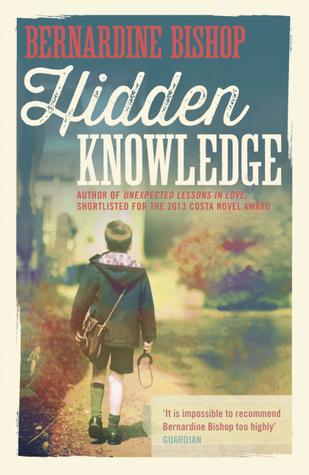

Bernadine Bishop, who died in 2013, has an interesting history: the youngest witness in the Lady Chatterley trial, she published two novels in her twenties, taught for ten years in a London comprehensive, before retraining as a psychotherapist. On retirement in 2010, she returned to writing fiction, with her first later novel, Unexpected Lessons in Love, which drew on her experience as a mother undergoing cancer treatment, shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award in 2013. If you’ve followed my series on fictional therapists, you’ll appreciate that I was intrigued when I read that Hidden Knowledge stems from her experience as a therapist.

The voice is light and mildly humorous, if perhaps a little old-fashioned, heavy on dialogue and reminiscent of the work of Barbara Pym. This was perfect for portraying the first-world dilemmas of a woman like Julia (p70):

The trouble with being single, she thought she made up her face in front of the mirror, was that you had to have so much social life. She drove to her dinner-party, became fairly engaged in some of the conversation, did not meet a possible man, and drove home, sober.

but felt rather light for the serious issue of child abuse. There is an extremely poignant section where, via an omniscient narrator, we see how the priest was implicated in Mark’s death. But, otherwise, the author gives Roger an easy time: while he fears the bullying he might expect in prison, and is grateful that his comatose brother will never learn of his offence, his sister and brother’s partner, while condemning the act itself, display none of the repulsion one might expect.

Roger, like both Julia and Tony, has had experience of therapy, but unfortunately this occurs off the page. I thought a therapist as character might have enabled a deeper, and more satisfying, exploration of clerical abuse and our reactions to it. Just as, in the late 1950s, Julia’s decision to have a child without a partner would have been so controversial as to require an entire novel, the sexual abuse of minors by those in positions of authority is too heavy an issue not to be the central subject of a contemporary novel in which it appears. The best example of this I’ve come across to date is John Boyne’s A History of Loneliness.

That aside, the loneliness of a middle-aged widow, in the character of Betty, is beautifully explored. Initially, Betty appears much older than her sixty years as she begins to recognise that filling her days with activities is no cure for loneliness. Without benefit of a therapist other than the author, she has a quiet dignity similar to that of Tess Lohan in Academy Street in her gradual discovery of the pleasures of her single state. The true heroine of the novel, she also faces up to the reality of her son’s death, so that I thought it somewhat harsh of Bernadine Bishop to allow her daughter and future grandchild to invade her privacy in the later chapters. But perhaps Betty has only herself to blame for not telling Julia her true feelings?

Thanks to Sceptre books for my review copy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed