| On the first day of every year, Aaliya has begun to translate one of the great works of literature into Arabic. What began as a personal challenge has become an obsession, with her thirty-seven translations stacked in boxes in the never-occupied maid’s room of her Beirut apartment, seen by no eyes other than her own. Unloved by her family, married at sixteen and liberated from that marriage three years later, her one female friend long dead and her one male friend disappeared, now she’s retired from her job at the bookshop these translations, along with the city in which she’s spent her entire life, are all that give her life meaning, all that keep her sane. Or do they? With her blue-dyed hair, with her emotional outbursts and fierce defence of her solitude, she seems on the brink of severing her ties to reality, increasingly alienated from all but the life of the mind. |

As a literary critic, she’s not in favour of an insistence on causality in modern novels (or even psychology, p96), although she understands the desire. She also wants a moratorium on epiphanies (p148), although it could be said that she’s given one at the end of the novel that features her life.

What has her reading taught her about life? I loved her ruminations on the craziness of war (p252):

At the heart of most antagonisms are irreconcilable similarities. Hundred-year wars were fought over whether Jesus was human in divine form or divine in human form. Belief is murderous.

and on what are sometimes referred to as “first world problems” (p52-3):

My books show me what it’s like to live in a reliable country where you flick on a switch and a bulb is guaranteed to shine and remain on, where you know that cars stop at red lights and those traffic lights will not cease working a couple of times a day. How does it feel when a plumber shows up at the designated time, when he shows up at all? How does it feel to assume that when someone says she’ll do something by a certain date, she in fact does it?

… When things turn out as you expect more often than not, do you feel more in control of your destiny? Do you take more responsibility for your life? If that’s the case, why do Americans always behave as if they’re victims?

Early in the novel, Aaliya echoes The Nearest Thing to Life in her reflections at the funeral of her former husband (p16):

Death is the only vantage point from which a life can be truly measured. From my vantage point, as I watched men I didn’t recognise carry my ex-husband’s coffin away, I measured his life and found it wanting.

Yet later she suggests something similar about her own (p159):

Giants of literature, philosophy, and the arts have influenced my life, but what have I done with this life? I remain a speck in a tumultuous universe that has little concern for me. I am no more than dust, a mote – dust to dust. I am a blade of grass upon which the stormtrooper’s boot stomps.

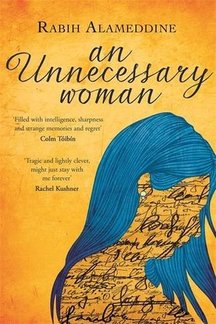

Despite the cultural differences, her stoicism in the face of loneliness is reminiscent of Tess in Academy Street. An Unnecessary Woman is published by Little Brown, who provided my review copy. For another novel about reading, see – or listen to – my review of Reader for Hire

RSS Feed

RSS Feed