| After escaping a fire in Paris that might have killed her bullying estranged husband, Helen rents a large and dilapidated house on the edge of the Yorkshire Dales, hoping for peace and seclusion. But she hasn’t bargained for the curiosity of the villagers, including Gil, a recently-retired journalist with time on his hands. After an Internet search throws up some disturbing information, Gil persuades Helen to tell him her story, which unfolds in a six-hour overnight conversation, reminding me of the mammoth therapy session in The Other Side of You. |

They said war reporters were the surgeons of the newspaper world. It was the adrenaline surge of having other people’s life stories in your hands, she supposed. Her response had always been the same: if reporters were the surgeons, then photographers were the snipers; high maintenance, aloof, riddled by doubt and driven by certainty.

I was drawn to this novel by a Guardian review by Samantha Ellis and by its association with my favourite Brontë novel, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. I was so sure I’d like it, I chose it for my book club read. As I turned the pages, I wondered what the hell a group of psychology and psychotherapy types who enjoy understated literary fiction with complex characters, would find to say about a middle-of-the-road plot with competent, but not inspiring, prose (and an irritating tendency towards single-sentence paragraphs). It turned out that this was probably the book we’ve agreed on most, inspiring most members to read The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

One of the things I liked in Anne Brontë’s novel was how Helen’s husband had punished her through his corruption of their son. This strand is much weaker in The Woman Who Ran, where the boy appears as the ghostly presence of an Iraqi child who was the subject of one of Helen’s prize-winning photographs, although her husband’s envy of her symbolic child (as in her work) was extremely convincing.

I received my copy of The Woman Who Ran from the publishers, HarperCollins.

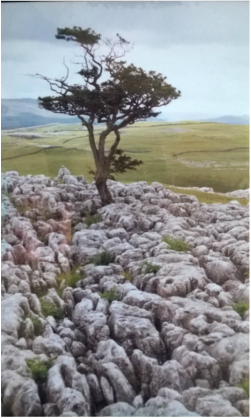

I enjoyed identifying the setting; if you know Yorkshire it’s not far from the asylum in The Ballroom, nor is it far from one of the finest examples of limestone pavement you could hope to see. With today’s (yes, I’m quick off the mark!) flash fiction prompt on the subject of erosion, I ought to have had a bash at describing the topography.

Above Malham Cove

After fifteen years, I was thrilled to bump into Jennifer. “You haven’t changed a bit!” As soon as the words left my mouth, I regretted them. She was still the happy-go-lucky woman I remembered. She couldn’t say the same for me.

Eric placed a proprietary hand on my backside. “Come on! We’ll be late.”

What could we be late for? We were on a weekend break. With a wooden smile, I made my apologies. At least Jenny couldn’t see the bruises beneath my clothes. The me she’d known would not have been cowed by any man.

As you see, I’ve chickened out (or played to my strengths) and let the title speak for the geology, while exploring the erosion of character and confidence in an echo of Helen’s experience in The Woman Who Ran. As the catalyst for the narrator’s discovery of her sorry situation, I’ve drawn on an unexpected, though in real life entirely pleasant, encounter with a woman I used to work with rather longer than fifteen years ago at a library event I did for my debut novel, Sugar and Snails, in Newcastle last week. Though Charli didn’t quite manage to read my mind and give me a squirrel last week, I do enjoy the way we can make disparate bits of our worlds join up.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed