| There’s no rain in California. The swimming pools that graced the homes of the beautiful people are nothing but rubbish tips, no-one can wash and drinking water is rationed. Just beyond Los Angeles, civilisation lies buried under mountains of moving sand. Most people have been evacuated to the camps out East; those who remain take their chances in this lawless environment. It’s not only the sun that is harsh. |

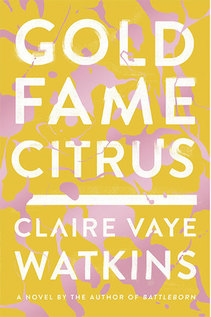

A cli-fi novel somewhat reminiscent, with the quasi-messiah, of Station Eleven, Gold Fame Citrus (named for the treasures that drew people to south-west America) is an engaging debut from Quercus books, to whom thanks for my review copy. Now and then, I didn’t quite get the Americanisms and cultural references, but enjoyed it all the same. With the intense heat, it also put me in the mind – albeit a potentially unreliable mind, given it’s a long time since I read it – of the classic dystopian novel, On the Beach.

| This reminder of Neville Shute gives me an opportunity to segue across to another Australian writer, this one actually alive, my blogging friend Irene Waters, who is asking for beach memories as part of her community memoir project, Times Past. Having survived meals in restaurants and washday blues, I thought I’d pitch in once more. |

For our family picnics on the beach, we’d pile in the car and drive a little further north to where the sand went on for miles. We did the usual stuff: building sandcastles; paddling in the shallows; queueing for ice cream and enduring cricket matches which catalysed my lifetime’s loathing for the game. With the breeze blowing away any heat, and protective strategies like shade and sun cream and covering up beyond the 60s British brain, we’d burn before we knew it; the price to pay, it seemed, for a day at the seaside. This picture of me and my dad, drying off after a rare dip in the sea, is on another beach further south, a real beauty spot, unfortunately in the lee of a nuclear power station, and thus possibly radioactive.

Exploring Europe in late adolescence, spreading out a sleeping bag in a secluded part of the beach stretched my money a little further. It took me a while to realise, however, that the perpetual feeling of tight and itchy skin was the result of washing in seawater.

Now I live about as far from the coast as it’s possible to get in Britain which, admittedly, on our small island, isn’t very far. When I want to commune with nature, I tend to prefer to take to the hills, although I’m still fond of the British coastline. To mark my fiftieth birthday, I was able to combine both, walking over the course of a couple of weeks from the west coast to the east, a celebration of friendship as much as scenery, after which I began writing what became my debut novel, Sugar and Snails. There’s a suggested trip to the beach in that, but it never comes to fruition; nor, despite the title, is there an awful lot of beach in my short story The Beach Where He Found It. But there’s a little more beachiness in my next novel, Underneath, scheduled for publication in May next year.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed