Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

These two recent reads are about marriages under severe strain. In the first, set in the southern USA, a woman turns to a mutual friend when her husband is sentenced to twelve years’ in prison for the crime of being black in the vicinity of a sexual assault. In the second, set in the UK, a family is in crisis as a result of the husband and father’s combat PTSD.

6 Comments

Humour is a tricky business, especially around serious subjects. Get it right, and you can entertain while inciting rage at injustice. Get it wrong, and you risk becoming the target of rage. So what did I make of these two comic novels? The first set in Blitz-blasted London, the second in contemporary Atlanta, which draws you most and are you able to guess which I’d prefer?

I recently read two novels set in England almost a century apart about young women returning to their parents after their marriages break down. Unfortunately for both of them, their childhood homes are stepping stones to something more terrifying than the confidence lost from relationship failures: in the first, Grace spends months on the streets; in the second, Clara is confined to a dismal mental institution.

These two novels about female friends from two different cultures and at different stages of their lives expose the power imbalance between even privileged and highly educated women and the men in their lives. The first is a thoughtful novel about middle-aged women in London; the second a lighter story about young adults in Saudi Arabia.

Where once it was religion that kept the poor downtrodden, now it’s capitalism as expressed in the Great American Dream, that we can all be winners if we set our minds to it. Both these novels transport the modern mind to a time and place where characters are conscious that not everything that happens is under their control. But that doesn’t stop them from trying to appease the superpowers or exercise free will. In the first, we meet a group of thirteenth century pilgrims sacrificing earthly pleasures for an easier eternity; in the second, a young woman in modern secular India grapples with the ancient Hindu concept of fate.

The titles themselves are reason enough to pair these recently published American novels. What I didn’t expect when I picked them from my TBR shelf is that they’d both feature the painful shock, especially among women, of Donald Trump’s election to president. The first zooms in on alienation, perceived inadequacy and a painful discovery of one’s own propensity to violence. The second forefronts the anxiety engendered by the climate crisis and rampant capitalism. I wonder if either of these authors is considering a sequel about their characters’ relationships with the coronavirus pandemic!

Strange bedfellows these two translations: the first an historical novel from France; the second a contemporary slipstream novel from South Korea. My excuse for linking them is an issue that was on my mind the day I finished the first and started the second, thanks to a non-fiction book I had ordered. Although women being blamed for sexual abuse and harassment is only a minor issue in these novels, it’s so important I make no apology for ushering it into the limelight.

I’ve recently read two historical novels about morality with surprising echoes of our current pandemic. The first is a fun story set in 17th-century London about a young woman concerned about losing the respect of her relatives when she turns to prostitution after becoming homeless during the Great Plague. The second is set in a copper mining community in 1850s South Africa, where lives are lost because the owners put profit before people.

Is there discrimination against women writers? (Is there even more discrimination against older women writers?) Probably but, there being even worse things to get hung up about right now, I’ll gloss over the fact that these two novels about under-appreciated female writers – one in 1960s Iceland, the other in 21st-century New York – come from fairly successful female authors. With a couple of caveats, either or both would make great lockdown reads.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a mother in fear of penury will sacrifice a daughter in marriage to a man she does not love. Jane Austen famously satirised such mothers two centuries ago; Janice Hadlow’s debut novel gives Mrs Bennet’s unloved middle daughter Mary a makeover in similar style. Angie Cruz, while perhaps not intentionally channelling Pride and Prejudice, draws on the painful mother-daughter dynamic in her Women’s Prize longlisted novel about 1960s migration to New York from the Dominican Republic.

My two most recent reads are of novels that map cultural changes within two very different communities. The first is set in rural Ireland during the BSE crisis at the end of the twenty-first century, as more and more people turn their backs on a traditional form of butchering. The second starts and finishes in the two decades before the first begins, in the community of recent migrants to the UK from Bangladesh. While both include scenes of violence, the second is overall a cosy story of adaptation and resilience, while the first is a literary novel of linguistic and psychological depth.

How do boys become men and what happens to those whose journeys go wrong? The first of these novels, set in Scotland, looks at what boys learn from their fathers when the son of a bully goes on to murder his family, apart from his younger son. The second is about a traditional coming-of-age ceremony in South Africa and the physical, psychological and social consequences of a botched circumcision.

I’ve read a lot of excellent historical novels by female authors, but they don’t always (and this isn’t necessarily a criticism) forefront the female experience. For Women’s History Month I’ve plucked from my shelves, real and virtual, a few that particularly highlight the lives of women in days gone by. Firstly, I’m recommending 8 novels fictionalising famous and relatively unknown women; secondly I’ve selected 8 (from potentially hundreds) exploring historical happenings through a female perspective. All are from female authors who might yet become historical figures themselves!

Allow me to introduce you to a pair of novels about literally and metaphorically staying afloat in choppy waters. The first is a cli-fi translated novel about abandoned children; the second a historical debut about a woman at sea in a man’s world. Both are page-turners, so read on!

History with meddlesome jinns and fairies: The Ninth Child & The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree29/2/2020 My two final reviews for February are of historical novels with touches of culturally-appropriate magic realism. They also feature the losses and gains of relocating from a major city to a rural area in a period of rapid social change. The first is about public health and engineering in nineteenth century Scotland; the second is set between the late twentieth century and the present in post-revolutionary Iran.

As these might be the only non-fiction books I read this year, I was keen to link them. So following on from two novels about dislocation, I’m delighted to share reviews about the opposite. Unfortunately I got myself lost in the first, aimed at readers with a more solid grounding in Greek and Roman antiquities, but managed to navigate better through the second, which is about literally and metaphorically finding and losing our way.

That’s right, both novels are about daughters: the first a debut about the claustrophobic bond between mothers and daughters exacerbated by the claustrophobic island setting; the second a translation from Hebrew set in late 19th-century Russia about the consequences of a father teaching his younger daughter his unusual trade. Of course there might be other connections but, as you’ll see if you read to the end, right now, I’ve got fictional daughters on the brain.

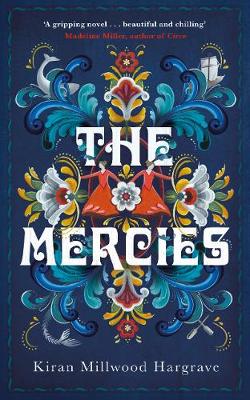

In what circumstances is it acceptable for women to abandon their traditional roles? What are the consequences if they should do so ill-advisedly? Although these two novels are set in different times and cultures to my own, they raised questions for me as to how far we can safely step out of line. The first novel pays homage to the forgotten women of Ethiopia who took up arms when the country was invaded by Mussolini’s troops. In the second, set in seventeenth century north Norway, the women have no choice but to do the jobs previously carried out by their menfolk when a storm at sea wipes out most of the male population, only for some to find themselves accused of witchcraft a few years later.

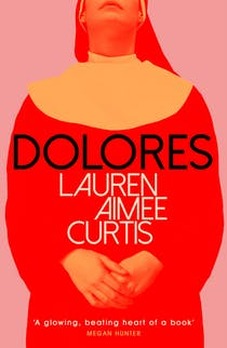

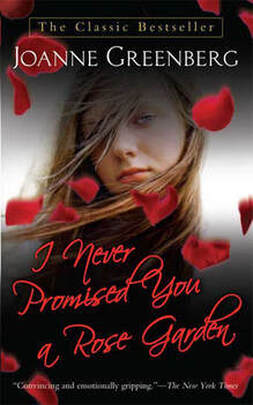

In these two novels, a teenage girl needs a safe place to retreat from the world, but the sanctuary she’s chosen won’t easily let her go. In the first, a convent provides shelter to a girl fearful of the consequences of an unplanned pregnancy; in the second, a psychiatric hospital offers a welcome respite from the strain of appearing sane. It’s pure coincidence that the main characters’ names – Dolores and Deborah – begin with the same letter and that both remind me of my forthcoming novel, Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home.

|

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed