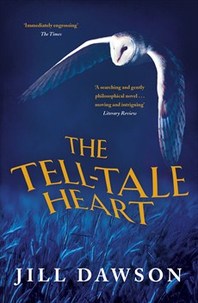

Patrick Robson, a history professor with thirty-odd years of over-straining both his literal and metaphorical heart, wakes up in hospital following major surgery with his ex-wife at his bedside. Two hundred years apart, two teenage boys experience their sexual awakening under the wide skies of the Fenlands, and discover how the odds are stacked against those not born into wealth in cash or land. What connects the three main characters is that Drew Beamish was carrying a donor card when he was killed in a motorcycling accident, and Patrick has received his heart, while Willie Beamiss, only just escaping hanging or deportation for rioting, is one of Drew’s ancestors, and commemorated in the local museum.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed