The Mere Wife by Maria Dahvana Headley

Willa is also a survivor, although her wars have been fought in the social sphere. The daughter-in-law of Herot’s founder, she also has a young son. The boys are seven when Gren, unbeknownst to his mother, sneaks down the mountain to play with Dylan. When Willa discovers claw marks on the piano and windows, she calls the police[2].

Despite both mothers’ best intentions – Dana making a home deep inside the mountain; Willa dismissing her son’s talk of Gren as an imaginary friend – the bond strengthens between the boys. But the battleground between the adults is quickly bloodied: Willa losing a husband; Dana an arm.

Of course, the story can’t end well, but its telling is delightful: beautiful language; credible fantasy; a gloriously bitchy Greek chorus of society widows and wives. Published by Scribe, this exploration of the light and dark sides of mothering, and how the threat of losing what we cherish can make monsters of all of us, has earned its place on my favourites shelf.

[1] Although within sight and sound of the suburbs, mother and son set traps and forage for food as if they were deep in the Siberian taiga.

[2] I might not have mentioned it if it wasn't season, but she insists on them coming out on Christmas Day. Willa's already outed herself as a Christmas martyr (p54):

She ordered the goose from a retailer that gave the goose's entire family tree. It's a heritage bird. She ordered heirloom onions and grains for stuffing. There was a ten-page photo spread in her mind, her Christmas dinner as photographed for the masses. Tagged, envied. Now the goose looks yellowish and nervous.

If that's your thing, you can find eight more far from perfect fictional Christmases on Annecdotal.

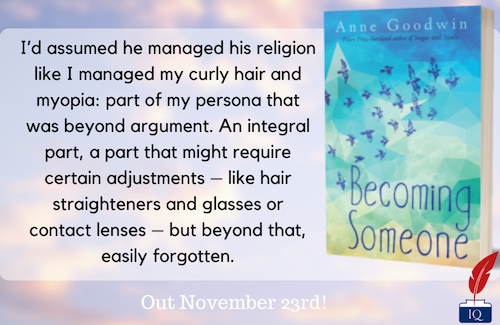

| There are a range of mothers – fierce, feeble, fearsome, failing – in my short story collection, on the theme of identity, Becoming Someone, but I’ve picked out Reuben’s mother from “Rebekah’s Foreskin” for special mention in her attempt to protect her far-from-monstrous child. |

The River Capture by Mary Costello

Ruth Mulvey, a social worker in Dublin of around Luke’s age, has grown up three miles away, although the two have never met until she shows up at his house looking to place a homeless dog. There’s an instant connection and, over the ensuing thirty days, a tentative drawing closer, although Ruth has reservations about Luke’s recent sexual relationships with men as well as women.

There’s a promise that time and trust will demolish that obstacle to their future happiness, until a revelation from Ellen proves a far firmer barrier. Staunchly loyal to family, having nursed another aunt through terminal cancer, Luke cannot countenance continuing a relationship that will cause Ellen pain. Yet, in losing Ruth, he risks losing his mind.

Ellen’s tragedy contains echoes of Mary Costello’s debut, Academy Street, about the Irish exodus to America, but Luke’s preoccupations and identifications are with Stephen Dedalus, Leopold Bloom and their creator, James Joyce. It’s likely my own unfamiliarity with Ulysses will have compromised my enjoyment of the novel, but I did relish the lyrical scene-setting chapters as Luke goes about his humdrum existence, reminiscing and cutting off painting the house.

In the second half, as Luke struggles to accommodate his aunt’s shocking disclosure, I found the style (of question and answer I believe to be borrowed from Joyce) too distancing, although I did appreciate his grandiose ruminations as a form of manic defence. Although he doesn’t descend as far into madness as I expected, his loss of ties to reality (which Freud claims are love and work) makes this credible. Thanks to publishers Canongate for my review copy.

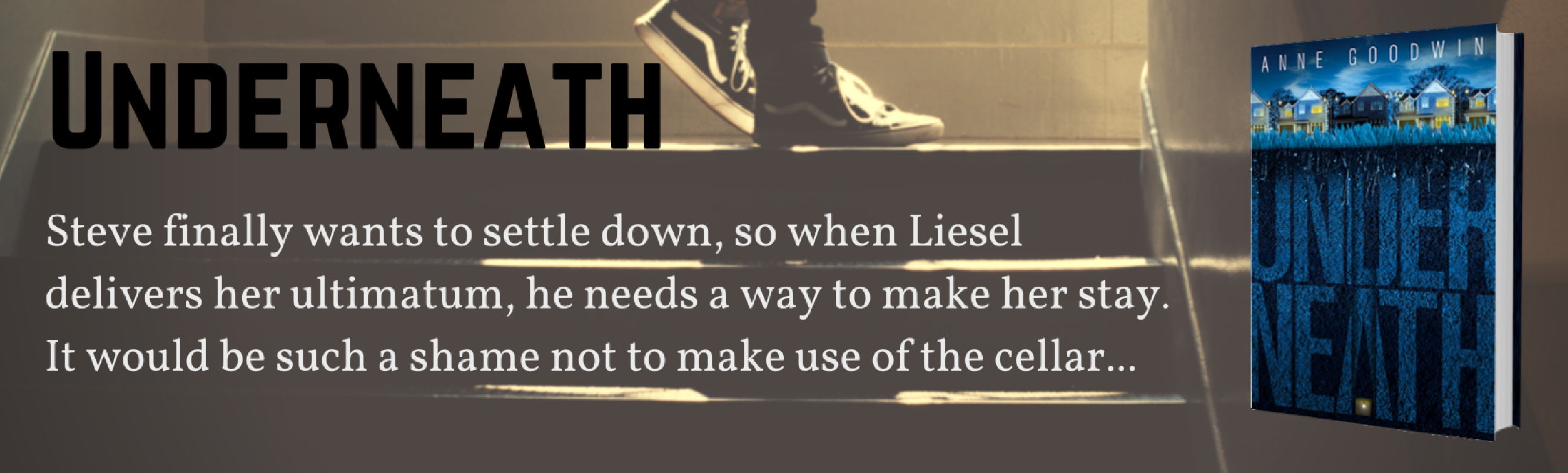

If you’re drawn to stories about men unravelling when a relationship goes sour, you might like my novel, Underneath. Although, be warned, my character is a lot more disturbed and disturbing than Luke!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed