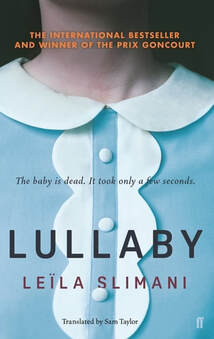

Lullaby by Leïla Slimani translated by Sam Taylor

We backtrack to Myriam, a French-Moroccan lawyer, falling out of love with childcare and, along with her husband, interviewing prospective nannies so that she can return to work. Louise seems perfect, able to soothe and entertain the children, as well as cooking meals for the parents and keeping the apartment spick and span.

Louise has problems, however, and, a widow with no friends and seemingly estranged from her own daughter, begins to perceive herself as a member of this young family. Initially, this suited Paul and Myriam, as they could rely on Louise to work late, and even took her on holiday to Greece. But some of her behaviours are unacceptable, such as putting make-up on their daughter, and others are plain weird. But when the relationship has become so crucial to their family’s functioning, how can they let her go?

Despite the attention-grabbing opening, I found this a quiet novel about the fragile dynamics of the employer-employee relationship when the task is emotionally difficult to delegate and the workplace is the family home. An easy read, but forgettable, which doesn’t fully deliver on why Louise went so far, unless a late reference to a hospital admission “for mood disorders” was meant to explain it. Having been underwhelmed by another of the author’s novels, Adèle, about a young mother’s addiction to somewhat joyless extramarital sex, I probably wouldn’t have read this if hadn’t been chosen for my book group – and reading on Kindle doesn’t always help.

If you’re interested in the themes of childcare, murder and mental health you might enjoy Our Fathers by Rebecca Wait about toxic masculinity and coercive control, or Little Bandaged Days by Kyra Wilder, about a socially isolated young mother’s descent into madness.

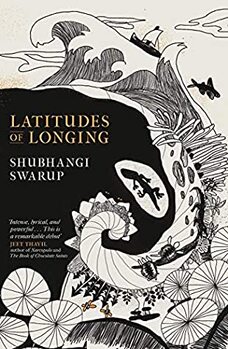

Latitudes of Longing by Shubhangi Swarup

Mary, a widow, with her own sad history of poverty, violence and loss, is recruited as a nanny. When the child outgrows her, she learns of the whereabouts of the son she abandoned years before. Plato – a name he assumed for his interest in philosophy – is imprisoned in Myanmar for the temerity of student agitation against the oppressive regime. After ten years of captivity, punctuated by periods of torture and solitary confinement, his mother is there waiting when – seemingly as the result of a chance encounter between the dictator and a Buddhist monk – political prisoners are released.

Late in the novel, Thapa, the drug smuggler who reunites mother and daughter, poses the rhetorical question of what makes a story a story. For me it’s psychology, but this novel is shaped more by history and location, the baton passing between characters as they journey through decades in a region defined less by national boundaries than by the geological fault line in the core of the earth. And sometimes they fall through the cracks.

As did this reader, I’m afraid, and would have appreciated more history and less of the spiritual stuff. It’s hard to admit that I ‘enjoyed’ the chapters on Plato’s imprisonment the most, even as I flinched at the cruelties he endured. And no-one’s to blame that I struggled with the sordidness of contemporary Kathmandu, which stood in stark contrast to my mostly pleasant memories of the time I spent there in the 1980s. We all bring our biases to do the stories we’re told.

A bestseller in India, I read this debut in the form of an advance proof copy from British publishers riverrun.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed