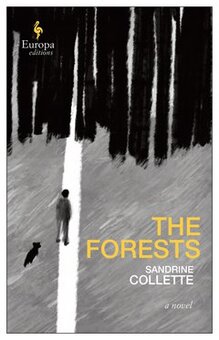

The Forests by Sandrine Collette translated by

Alison Anderson

His student life now devoid of meaning, Corentin sets off on foot to the village he grew up in, two hundred miles away. He doesn’t know what he’ll find there, if anything, but it’s his only chance.

I wasn’t sure how to read this novel, let alone review it. Spanning several decades, it starts as one thing and turns into something else. In retrospect, the themes are consistent with those of the two other novels I’ve read by this author, courtesy of Alison Anderson’s translation and publisher Europa editions.

The Forests starts with a pregnant woman, locked up by her deceased husband’s grandmothers to prevent her getting an abortion. As you might expect, this doesn’t provide the ideal circumstances for bonding with her unwanted son. When she neglects her baby, I detected echoes of Nothing but Dust, a startlingly honest account of the harshness of life on the Patagonian steppe and the impact of a mother’s inability to love herself or her sons, which was one of my favourite reads of 2018.

However, when Corentin turns five, his mother dumps him on one of those grandmothers and exits the story. Although not particularly demonstrative, the elderly woman provides his first experience of love. Even so, I found it hard to believe that someone so neglected in infancy would make it to university, as Corentin does.

Next the novel moves into the territory of Just after the Wave, a cli-fi story about the plight of a young boy and two of his siblings after a tsunami has destroyed the known world. I’d forgotten, until I looked back at my review, that this novel is also about abandonment and couples breeding like rabbits. But, as far as I could make out, Corentin’s attachment issues didn’t affect his response to the crisis. He could’ve been anyone.

I did enjoy the second half of The Forests when Corentin is rebuilding his life, but overall I found it uneven and less engrossing, and less psychological, than her other two books.

The Bones of Barry Knight by Emma Musty

Meanwhile, Saleema and her friend are making the best of their childhood, despite the deprivations of the refugee camp. Ana, a journalist, and Omar, Amanda’s former partner in both senses of the word, are separately reviewing their heritage. Sol is tentatively learning to live again after his girlfriend’s death in a hit-and-run accident for which he holds Barry responsible.

Despite a potential surfeit of POV characters, I found it easy to engage with this novel and the weight of the issues it addresses never drags down the story. The author’s expertise as an activist ensures we’re in safe hands (without being preached at) and, when the tragedy unites her cast, she delivers a satisfying twist. Having enjoyed the author’s debut, The Exile and the Mapmaker, I’m delighted that her second novel is a contender for my books of the year. Thanks to publishers Legend Press for my advance proof copy.

I don’t have the experience to write with such depth about the refugee situation, but it does sometimes feature in my 99-word stories. One of these – my 100th short-story publication – was recently published in an anthology, Poetry and Settled Status For All, edited by Ambrose Musiyuwa, a response to the plight of migrants and refugees during the pandemic. I’ll be reading my prose poem along with other contributors to the collection at an online event next week. Do join us if you can. Click the link for more information and to register – it’s free!

Poems for a challenging world 7pm (UK time) on Monday, 21 March

I was already aware of pi day when Charli posted the prompt for this week’s flash fiction challenge: free pies. While my TikTok on the topic is characteristically silly – click on the dozy-looking face to watch it – my 99-word story returns us to the serious slant in the novel, The Bones of Barry Knight.

Encased in melt-in-the-mouth pastry, the fruity filling tasted of home. Even as Mama urged us to nibble like hamsters, our sticky hands reached for more.

We hadn’t heard of the rock star who brought this feast to the refugee camp but we vowed, when finally granted asylum, we’d be his biggest fans. We changed our minds later, holding each other’s hair back from our faces in the stinking latrines. No water to wash away the vomit or slake our thirst, we cried in chorus. Mamma was right, the pies were too rich for starving stomachs. He should’ve brought rice.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed