With emotionally distant parents and a father demanding nothing less than excellence from his offspring, Miri has grown up as a fighter, afraid to show her vulnerable side. Like the country of her heritage, she’s proud, unwilling to succumb to the demands of her captors, possibly thereby exacerbating the punishment she receives. She argues, refuses to take responsibility for the country’s problems, even though, through the eyes of her all-American husband, the gap between rich and poor is shown to be obscene. As with Melanie Finn’s novel, Shame, there is a question of whether the violence is inevitable, and whether those who do nothing to resolve the grinding poverty are complicit in its continuation.

Yet Miri pays dearly for her parents’ ostentatious displays of wealth in an impoverished land. In the before, as she puts it, she’s been comfortable in her body – breastfeeding, running, making love – just as she’s been comfortable in the lawless country of her roots. When her abused body becomes a torment, her only chance of survival is in dissociating from it and the woman she used to be. In her feral, untamed, state she perceives herself as dead, no-one, referring to the wife and mother of the past in the third person.

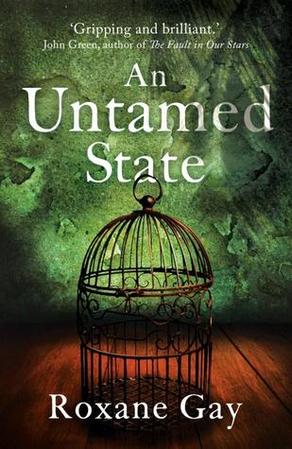

On release, her anguish continues, even intensifies, as, psychologically, she’s still in her cage. She cannot give voice to what she’s gone through; indeed, she can hardly speak at all. Touch is unbearable, even from her husband and child, or the doctors who desperately need to treat her wounds. Her family, while sympathetic, can’t understand how she doesn’t recognise she’s free. Finally, it’s on the remote farm with the mother-in-law who never really liked her that healing can begin.

Lorraine’s unflappability was a godsend, but it did make me wonder what would have happened to Miri had she not pitched up at the farm. As a study in both the experience of terror and its aftermath, An Untamed State brought home to me more than anything else I’ve come across recently how poorly modern society accommodates those who’ve lost their way. When the gulf between the damaged and undamaged is as great as that between rich and poor, it’s little wonder that our attempts to assist the vulnerable are often inadequate. Refugees seeking asylum in the rich countries of the West are expected to find the words, and the courage, to give an account of their unspeakable persecution in a rational manner. Those driven mad by the gap between how things are and how they should be are diagnosed and medicated and instructed to get dressed. The concept of asylum for the mentally disturbed, originating as a humane form of refuge from the demands of the world, has sadly fallen into disrepute.

I wasn’t totally taken with the end of the novel, which fast-forwards over a number of years taking in a return visit to Haiti after the 2010 earthquake (the subject of another novel I reviewed, God Loves Haiti), less because of the content than nostalgia for the earlier chapters which were so vividly immediate. It’s hard to believe that this is a debut novel, leaving me in awe of this writer’s brilliance. I urge you to read it. Thanks to Corsair for my proof copy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed