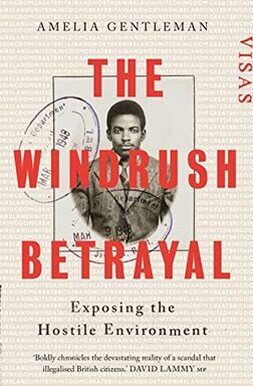

The Windrush Betrayal by Amelia Gentleman

Having followed the excellent Guardian articles, and being a reluctant non-fiction reader, I hesitated to fork out for the hardback. But independent journalism needs our support and, despite the rage-inducing subject matter, it’s so well written (personal, but without making it about the author, as I’ve sometimes found in journalist-penned books) it made for worthwhile garden reading during this recent week of September summer weather. And with the issue creeping into my very contemporary WIP – although I’ll have to doctor the dates slightly – it was a necessary read.

The cruelties are reminiscent of 1930s Germany: people lost their jobs (employers understandably reluctant to risk the £20,000 fine for employing an illegal immigrant); their homes (as landlords faced similar penalties); access to state benefits they had paid for via national insurance contributions. Some had their bank accounts frozen; some were denied healthcare; some, like Paulette, were whisked off to detention centres with little warning and forced to swap their clothes for prison-style uniform.

Victims faced further hurdles when attempting to correct what seemed to be an administrative error. A decade of austerity left government departments stripped to the minimum, charities underfunded and no access to legal aid for immigration cases. Anyone who surmounted the hurdles to speak to a real person got the typical call-centre script. The onus was placed on the individual to prove their status, even when accessing relevant data – such as tax records – would be so much simpler for the bureaucrats. Could you produce three pieces of evidence for each year you’ve lived in the country you call home?

The Kafkaesque nightmare is revealed in the crazy rationalisations in a letter sent to one man outlining why his case had been refused (p57):

you have been working within the United Kingdom illegally … You have therefore shown that you are resourceful … making an independent life for yourself in a foreign country. The skills and experience you have gained … should stand you in good stead for obtaining gainful employment and your return to Jamaica.

Some were so demoralised by the bullying, and fearing the humiliation of forced repatriation, they returned voluntarily to countries where they had no family, friends or prospect of work. Meanwhile, the landing cards that proved they had entered the country legally as children, stored by the Home Office for decades, were destroyed.

It’s both encouraging and depressing that the publicity generated by Amelia Gentleman’s investigations led to a government U-turn: with the standard oleaginous apologies, the resignation of the minister responsible (rehabilitated to another senior post in the next reshuffle) and the relevant documents being couriered to people’s doors. A compensation fund was promised, albeit with a cap of £500 for legal bills (around a fifth of the minimum needed) and a mere £1000 payment for those coerced into returning to unfamiliar lands (p287). At the time of writing – the book was published by Guardian Faber in June 2019 – many affected were still awaiting both compensation and individual apology.

Is any compensation sufficient for years wasted fighting for your basic rights? Some have died in the process – or soon afterwards, including Paulette Wilson earlier this summer – or been worn down by the stress. Given that most of those betrayed are around my age, I sometimes bristled at the author’s occasional reference to them as elderly. But the fact is that, like my grandparents’ generation, harsh circumstances make sixty-something old.

With Brexit and the continuing anti-immigration fervour – incidentally, the hostile environment policies failed in their objective to save taxpayers’ money (p286) – something similar could easily happen again. Now rebranded as the compliance policy, the underlying attitude to undocumented residents has not changed. First they came for the …

Act of Grace by Anna Krien

Nasim has lost both parents to the barbarity of Saddam Hussein, and suffered horrifically herself, but she manages to transform Toohey’s mistake into an opportunity, albeit at significant cost.

Meanwhile, Toohey’s son, Gerry, grows up anxious and somewhat aloof from his peers, nurturing a dream of visiting cowboy country in Western USA. Of course, it’s not as he expected but, learning about the disadvantage experienced by Native Americans, his travels catalyse his personal growth.

With her father disabled by early-onset dementia, Robbie is more interested in the injustices meted out to Australia’s indigenous peoples. Leading an art project among the Anangu of Uluru proves a challenge, and perhaps the chance for reconciliation with the hidden history of her own heritage.

With fine writing, important topics and apparently meticulous research, I loved this novel until about halfway through. While these praise-worthy elements never faltered, the sheer quantity of material meant my enthusiasm waned. Although the four threads interconnect, and at just over 300 pages it isn’t overly long, I think it would have worked better as two or even three separate novels. Such a shame as these are fascinating stories, especially the parts set in Australia and Iraq. Thanks to publishers Serpent’s Tail for my review copy.

| Also tangentially related to this novel, my short story, “Shall I show you what it’s like out there?” about a young man returning from Iraq – set in a hospital A&E department long before the pandemic – has recently been published by Blue Lake Review. Shall I read you the opening? | |

| The mouse infestation Toohey confronts on a chicken farm in Act of Grace, seems a good jumping off point for my response to this week’s flash fiction challenge. But my thoughts went to the various development projects I was privileged to visit decades ago in India, including an ashram in rural Gujarat supporting indigenous tribal people or Adivasi. Unfortunately, my BOTS is more light-hearted and Euro-centred so doesn’t do justice to that work. |

I felt honoured, in the rural areas, to be invited into people’s homes, conversing through smiles and gesture. But I needed to keep my wits about me: the poorer people were, the more generous their hospitality, and I didn’t want them going hungry because a white woman had come to visit. A simple shack, the bathroom a field, the kitchen a pot on an outdoor fire, yet their few possessions gleamed. I didn’t worry about hygiene until, hearing a xylophone tinkling, I saw mice scurrying along the shelf stacked with aluminium plates and tumblers, and my hosts just laughed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed