The opening of Lucky Us seemed promising:

My father’s wife died. My mother said we should drive down to his place and see what might be in it for us.

She tapped my nose with her grapefruit spoon. “It’s like this,” she said. “Father loves us more, but he’s got another family, a wife, and a girl a little older than you. Her family had all the money. Wipe your face.”

Oh, how that mother had me hooked! She seemed much more resourceful in accommodating to the duplicate family than the poor woman I’d left contemplating the cracks in the ceiling in a recent flash. Would the narrator follow her lead? I wondered. Or would she struggle to adapt, like Mary, in Geoff LePard’s novel-in-a-flash? What I didn’t anticipate was that she would abandon both her daughter and the novel only four pages on. Reader, I was bereft. Rudderless, despite, I now discover, having been warned this would happen by the blurb. (But we don’t pay much attention to blurbs, do we?)

Eva is twelve when she meets Iris, her father’s other daughter. Over the next decade, we follow their fortunes as Iris seeks stardom in the movies in 1940s America and Eva follows in her slipstream. Through the sisters and their various friends, lovers and hangers on, the novel shows us Hollywood hypocrisy, new-money airs and graces, post-war plastic surgery and the internment camps and repatriation of supposed “enemy aliens”. There are even a few scenes on tarot that had me wondering about extending the criteria for my series on fictional therapists. All very interesting and entertaining, related with that touch of humour evident in the section I’ve quoted above, but I felt rootless, longing, despite my general refusal to bow to the law of motivation, for the narrator to have a little more agency, to come out and tell us what she wants. As Charli Mills says, motivation is movement but movement without motivation is passivity. With the lack of a clear narrative arc, Lucky Us resembled memoir or a truth-based story and, in my mind, that’s not necessarily a compliment.

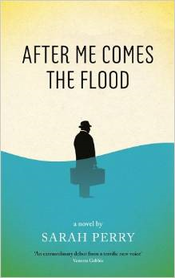

I was drawn to After Me Comes the Flood by John Burnside’s review in the Guardian. A writer of poetic and weirdly disturbing novels, I was happy to go by his recommendation and further encouraged by the novel’s longlisting for the Guardian first book award.

John Cole, a London bookseller without any customers, decides on a whim to drive up to Norfolk to visit his brother. But he never arrives, stopping off instead at a house in the forest where, to his surprise, he seems to be expected. There he remains for the next seven days, occupying the room and wearing the unwashed clothes of his almost-namesake, sharing the daily round with the longer-term residents, an assortment of waifs and strays and refugees of the mysterious St Jude’s, alternating between a sense of belonging and dreadful guilt. John’s headaches, the heatwave and peculiar odours, the curious absence of birds and the isolation of the country house, suggests all is not normal but I struggled to work out quite how abnormal it was intended to be. The odd characters seemed to float through the house like ghosts, becoming realised, not through their actions and interactions, but by the back stories that were gradually revealed. There were mysteries, such as the source of the letters sent to the fragile Alex, but I felt no particular satisfaction in their resolution. As with Lucky Us, my sense, as a reader, of being insufficiently anchored, reflected the characters’ lack of confidence in their own existence:

Sometimes he sat stroking the back of his hand, feeling the slide of skin on skin and wondering if his touch had always been so slight and so brief – surely he’d once felt its ridge and groove in the whorls of his fingertips? He fell to wondering if he were really there at all – here was his hand on the door, here his feet taking turns on the carpet – but what if his place in the world was not secure, like a tooth loosening in its socket? (p134-5)

reminiscent of the theme in In Search of Solace of identity as constructed from others’ perceptions of ourselves.

I understood the title in terms of Alex’s fear of the dam breaking with its parallel in the fear of mental collapse. But this seemed more a novel about groups: the loyalty and lack of questioning of those who are “in” and the twin threats of abandonment by versus loss of individuality within the group.

Thanks to Serpent’s Tail for my review copy of After Me Comes the Flood, which was published on 3 July.

Lucky Us is published today by Granta – thanks to them for my review copy. For other novels set in the same period, see my reviews of Those Who Save Us, I Can’t Begin to Tell You and The Undertaking (coming soon). For another novel I appreciated more in retrospect, see my review of The Long Shadow. For another novel on rebuilding collapsed social structures, come back next week for my review of Station Eleven.

| Have you had ever had that experience of struggling to get hold of the essence of a novel you’re reading? Did you manage to access the theme in the end? Comments welcome on any aspect of this post. | |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed