Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

We might be marking the centenary of start of the First World War this year, but here on Annecdotal there’s been an unexpected focus on the Second. From Louise Walters’s Polish pilots and land girls to Elizabeth Buchan’s code breakers and Danish resistance workers, from Audrey Magee’s Nazi marriage of convenience to Richard Flanagan’s Japanese prisoners of war, and forward in time to Peter Matthiessen’s Holocaust Memorial, we’ve viewed it from a range of angles but hadn’t, until now, considered the dynamics of the occupying powers overseeing the de-nazification process of a defeated Germany in the years immediately following the war. Step forward Rhidian Brook and his cast of characters strutting the rubble-strewn stage of a bombed-out Hamburg in 1946: Colonel Lewis Morgan, trying to bring compassion to the reconstruction of the city of shattered buildings and broken spirits; his grieving wife, Rachael, with mixed feelings about being reunited with her husband, blaming him for the death of their eldest son; Edmund, their eleven-year-old, whose pre-programmed prejudices cannot withstand his adventurous spirit; and the widower, Herr Lubert, and his teenage daughter, Frieda, whose palatial home they come to share. Add in Ozi, leader of the bunch of feral kids begging cigarettes from the soldiers to swap for bread or other items on the black market of use to the post-war German resistance, and we’re set for powerful drama on both a human and global scale.

15 Comments

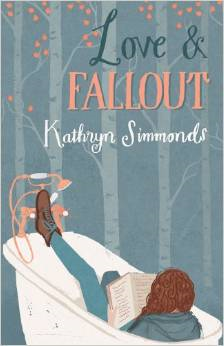

In the midst of my writing, when I’m floored by a factual question to which neither Google nor my encyclopaedic husband can furnish the answer, he tells me to make it up. After all, it’s fiction I’m creating not the instruction manual for launching a rocket to Mars. While close attention to detail lends our work credibility, we should also cut ourselves some slack. It would be unreasonable to expect us to get everything right. I’ve often wondered, as I’ve picked fault with my nine fictional psychologists and psychotherapists, if I’m being overly harsh. (I’ve wondered about that even more after reading a Catholic priest’s condemnation of John Boyne’s excellent A History of Loneliness in The Irish Times.) Surely it’s the story that matters above all else? While I’d defend the writer’s right to offend, many would prefer not to perpetuate unhelpful stereotypes. As M Kelter describes in his post Why Fictional Therapists Suck, inaccurate portrayals of psychotherapists in fiction can do real harm by putting people off accessing the help they need. So how do you create a credible fictional psychotherapist? While I can’t offer the definitive guide, I can suggest, based on my reading and on my experience as both therapist and therapped, some pointers:  On the night after Christmas, a middle-aged woman picks up her pen to write a letter to her estranged friend, Nina, without knowing where she might be or even whether she is alive or dead. Although they have had no contact for more than a decade, the pair have been friends since childhood and, for a few years shared a house as adults along with the narrator’s husband, Nicholas, and Teddy, their young son. Ironically, the narrator addresses her erstwhile friend by the name Teddy assigned to her on their first meeting, although as the novel progresses, its accuracy becomes more apparent (p158) Butterfly: settling on nothing, at the window pane basking or trying to get out, batting at the light as if baffled by this lovely form that is (so it thinks) some fragile decoration of its ugliness.  When Dan’s girlfriend leaves him suddenly, the last thing he wants is her ugly dog. But when there’s a hiccup in his plan to return the animal to the Battersea Dogs and Cats Home, the unloved dog transforms himself into Dan’s lucky mascot. Out of work for several months, Dan finds himself headhunted by the hip Indology advertising agency; they’re so keen to harness his skills as a copywriter, they even agree to him bringing his dog to work. Then follows a romp through office politics, romance and the revelation of family secrets (although why his dementia-stricken grandfather would have known about this particular skeleton in the cupboard I have no idea) to the heart-warming finale in which the title comes into its own. In my review of The Long Shadow, I said I’d be interested to see where Mark Mills would take his imagination next. I was hoping for darker, but what he’s done is slipped an extra initial (which I failed to notice originally) between his first and second names and moved sideways into another brand. This is lighter, nice-bloke-lit, Nick Hornby without the subtle humour and emotional depth.  Please give a thought to World Toilet Day tomorrow! Last year, I was very excited about my post on the subject and tweeted it several times through the day. Alas, although a year on it’s accrued its share of hits and comments, I was unable to garner any interest among my followers on the actual day. I leave you to speculate on the possible reasons, but I don’t think it was due to losing out to more scintillating competition. My timeline was full of writers peddling their Amazon pages; okay, to be expected when one follows lots of indie authors, but hardly the zenith of creativity. Meanwhile, over on the #WorldToiletDay timeline, I was stumbling over erudite, amusing and moving posts, highlighting the centrality of “the great unmentionable” to public health and gender inequality. But you needn’t just take my word for it, have a look at these gems I’ve saved for you from last year:  If I'd meant to take a photo of my foot I'd have done it better If I'd meant to take a photo of my foot I'd have done it better While it’s often difficult to trace the creative process, I love how we build our fiction from seemingly random elements of our lives. A snatch of conversation meets with a snip of memory merged with the odd gait of a passing stranger and we’re off, incubating a story in our minds. We find a similar process in the blogosphere: prompts, questions and opinions the cue for our own next post. Sometimes the blending of ideas occurs unconsciously; sometimes the links are more intentional, as when I took great delight in satisfying two blog prompts with my bad-hair-day flash. This week, when Charli asked for a 99-word story about a photo bomb (a serious scene interrupted by something absurd or unexpected), I was still musing over Clare O’Dea’s post about horrible husbands in fiction. They make such great characters, yet they haven’t often taken a starring role in my own reading and writing. Nor are mine as deliciously evil as those Clare has dished up.  Alice’s husband is becoming increasingly critical and his excuses for his absences from the home more and more lame; is she right to suspect he’s having an affair? Vic, managing the hotel in Madeira previously owned by her parents, is delighted when her old friend Michael returns to work on the island; should she share her doubts about the honesty of his new girlfriend, Estella? Kaya dreams of studying philosophy at university but for now, having fled her feckless mother and her mother’s druggie boyfriend, she’s capitalising on her good looks as a stripper; can she leave this life behind? Three women at different stages of the lifespan, seemingly unconnected at the beginning of the novel, find their fates disturbingly intertwined. This is the last of the four novels published on 6th November (although the hardback of Strange Girls has been out since July) I’m reviewing this month. I was eager to read it after coming across a couple of reviews by bloggers who found this novel much more engaging than they’d expected. Having nothing original to say about the plot without stumbling into spoilers, I’d love to refer you to those reviews but I have to confess I’ve forgotten where I found them, so if you’ve come across anything about this novel that might be of interest to other readers, do please paste the link in the comments section below.  I was a latecomer to Nick Hornby’s writing. He was well into bestsellerdom when I condescended to pluck About a Boy from the library shelves, not expecting to find much connection with a writer whose first book was a memoir about his dedication to Arsenal football team. How wrong I was! Although I still haven’t read his memoir, I’ve discovered in his fiction sophisticated characterisation and psychological depth beneath deceptively simple prose. Nick Hornby excels at portraying the obsessions and eccentricities of ordinary people, and their psychological and social implications, with great humour and warmth. His last novel, Juliet, Naked, concerning the triangular relationship between a reclusive rock star, Tucker Crowe, Duncan, his most dedicated fan and Annie, Duncan’s long-suffering partner, was a beautiful study of creativity, intimacy and their absence. A mismatched couple is at the centre of his latest novel: set in mid-1960s London, Barbara is a buxom blonde from Blackpool with conservative sentiments; Jim a left-leaning Home Counties fellow with a job (under the then Labour government) at Number Ten. But as Barbara and Jim are the central characters of a highly successful TV sitcom, the reader gets to know them at one step removed: via the actors, Sophie (previously Barbara, the five-minute Miss Blackpool and the eponymous funny girl) and Clive (licking his narcissistic wounds at being relegated to the supporting role); writers, Tony and Bill, who meet in a police holding cell during their national service, kindred spirits who gradually drift apart; and the Oxbridge-educated director, Dennis, constantly challenged to defend his devotion to comedy within the still somewhat snobbish BBC.  I’m pleased to introduce two novels published in the UK tomorrow that combine comic farce with trenchant exposés of problematic political systems. The new novel from ‘that other’ Australian Booker Prize winner, Peter Carey, is not another treatise on dementia, but a political cyber-thriller on the collective forgetting of the dark side of Australia’s “special relationship” with the USA. While for many readers from outside that country it may be more a matter of ignorance than amnesia, with several cultural references passing over our heads, this is an important and engaging novel which marries the essential human factor to disturbing parallels with global politics today. The novel opens with Felix Moore, Australia’s last remaining left-wing journalist and typical feckless white male, reading about the worm that has infected the computerised control systems of thousands of Australian and American prisons, while awaiting the court’s ruling against him in a trumped-up defamation case. But historically it begins with the battle of Brisbane in 1942, when Australian and American servicemen fought each other on the city’s streets and Celine Baillieux, whom Felix encounters later at university, is conceived through rape. Thirty-odd years later, Australia is facing its greatest constitutional crisis with the (possibly CIA-engineered) dismissal of prime minister, Gough Whitlam, and his progressive cabinet, as Celine gives birth to her first and only child, Gaby, future cyber hacker and the world’s most wanted woman in 2010 (p 167): Stuck in a rut? Love and Fallout by Kathryn Simmonds and a triple flash for not-quite NaNoWriMo2/11/2014  Through most of the 1980s and 1990s a women’s peace camp was held outside the RAF base at Greenham Common to protest against the siting of nuclear missiles there. Thousands of women joined the camp for anything between a single day and several years, making it an important part of recent British sociopolitical history yet, apart from one as-yet-unpublished novel on the theme, Kathryn Simmonds’ debut is the first fictional account of the movement I’ve come across. Tessa is nineteen and fleeing a dead-end job and the humiliation of being dumped by her boyfriend when she packs her rucksack and sets off for Berkshire. Idealistic and naive, only her friendship with the aristocratic beauty, Rori, sustains her through those first few weeks of mud and cold and songs around the campfire, eventually culminating in a spell in prison. Fast forward thirty years and Tessa is the manager of a struggling charity, at loggerheads with her teenage daughter and, along with husband Pete, going through the motions of marital therapy when a friend, Maggie, nominates her to take part in a TV makeover programme. Initially reluctant, she agrees to the filming as publicity for one of her “causes”, but when the producer wants to focus on the “Greenham angle”, the memories from that late adolescent rite of passage come flooding back. |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed