Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

Although these two historical novels are very different, both sparked some deep reflection about the workings of the human mind, and especially how our reasoning and problem-solving is influenced by beliefs and assumptions which, in turn, are shaped by the times and cultures in which we live. Both are set primarily in mainland Europe – the first in the seventeenth century and the second towards the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth – and feature – predominantly in the first and latterly in the second – countries ravaged by war.

10 Comments

The digital revolution has massively changed the way we listen to music, yet vinyl has been revitalised in some quarters in recent years. Perhaps it’s no surprise that contemporary novelists should review their record collections in search of new ways of exploring the human condition. But two published within three months of each other? That’s quite a coincidence. Read on to see how these established British authors have addressed the topic in very different ways.

Lulu Davenport is the proprietor of Los Rocques, a clifftop hotel on the Mediterranean island of Mallorca, frequented by a certain type wealthy Brit who holds themselves aloof from the package-tour hordes. It’s also a popular hangout for the teenagers who spend their summers on the island, roaming freely after months of more orderly education abroad. For almost sixty years, Gerald Rutledge has lived in a small house just a kilometre away from The Rocks (as everyone calls it), but he’s rarely set foot on the premises. It’s not just because, having married a local woman and made his living from the land, he’s more assimilated into the Spanish community, but also because he’s persona non grata to Lulu following their brief and calamitous marriage only a few years after the end of the Second World War.  By the end of this week, I’m hoping to have completed the first round of my publisher’s edits of my forthcoming novel, Sugar and Snails. I’ve blogged before about the joys of collaborative editing but, I must confess, I haven’t always relished having someone else take a scalpel to my treasured words. However much we understand intellectually that the external perspective is vital, it can be difficult emotionally to accept that our darlings must be killed. This time, however, I’m delighted to see paragraphs scored through, sometimes entire scenes. I’m not saying that I agree 100% with my editor’s suggestions, but I do welcome the prospect of cuts. Given that I’d pared the prose down as much as I could before submitting, and a bit more on signing the contract, I am a little surprised that I’m so sanguine about additional extractions. I can’t believe it’s because, after so many years of writing, I’ve achieved a Zen-like state of acceptance; so what else could be going on?  It could be something relatively minor, like discovering the show-not-tell rule, or being persuaded that there’s a downside to praise. It could be as colossal as learning that the world is round, but a new idea or insight can be so powerful it knocks us off our feet. We’re thrilled or terrified, or maybe a bit of both, as the old familiar furniture rearranges itself in our brains, altering the essence of our very being. Naomi Alderman captures it beautifully in her novel The Liars’ Gospel at the point where Iehuda (Judas) is beginning to get to grips with Yehoshuah’s (Jesus) ideology: Iehuda allowed his mind to follow, across the map of the wide world, across the empires and kingdoms that fought and tried to rule and subdue each other. And he imagined what might happen if these words travelled from mouth to mouth, from mind to mind, from one city to the next to the next, if this simple message – love your enemy – were the accepted creed of all the world. He did not see how it could happen. (p85-86)  Sometimes these new ideas are so shocking we want to retreat from them, to go back to the time when we were secure in our ignorance. We are particularly likely to resist our new knowledge if it’s controversial or likely to be unpopular with the powers that be (including our parents). It’s said that Darwin (Charles, not Emma of This Itch of Writing fame, although there is a connection), a deeply religious man, struggled to accept that what he’d learnt from his voyage on the HMS Beagle didn’t tally with the biblical account of our origins. It’s also been argued – although others have disputed this – that Freud repressed or suppressed the histories of genuine childhood sexual abuse amongst his patients by relabelling them as fantasies. In the traditional telling of the Oedipus myth, the hero is on a journey towards uncovering the painful truth of his having killed his father and married his mother. However, in an alternative version of the story, which I first came across in a paper by the psychoanalyst John Steiner, it’s all about a cover-up: each of the characters has a vested interest in turning a blind eye to the knowledge of who Oedipus actually is. We can all collude in hiding from inconvenient truths. In my short story, The Invention of Harmony, I wanted to explore the dizzying sense of a new idea and the paralysing fear it can evoke in someone who lacks the courage or the social support to see it through. I found it challenging to set this story in the past (and blogged about my first attempt at writing historical fiction in the post Stepping tentatively back in time), not only because the daily life of my mediaeval nuns was so different to mine, but because of the everyday knowledge of which they would be unaware. But, of course, that was the whole point of the story: the discovery of and retreat from innovation. Although Sister Perpetua’s revolutionary idea was in relation to choral singing (any excuse – here’s a short clip of singing nuns – you'll see I managed the subject even in my responses to Norah's mind-blowing Liebster award questions), I’m sure the same could happen with any other form of creativity. What do you think? Have you ever had an idea that’s blown your mind? Have you ever turned your back on your own creativity? Look forward to your thoughts, however challenging they might be. |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

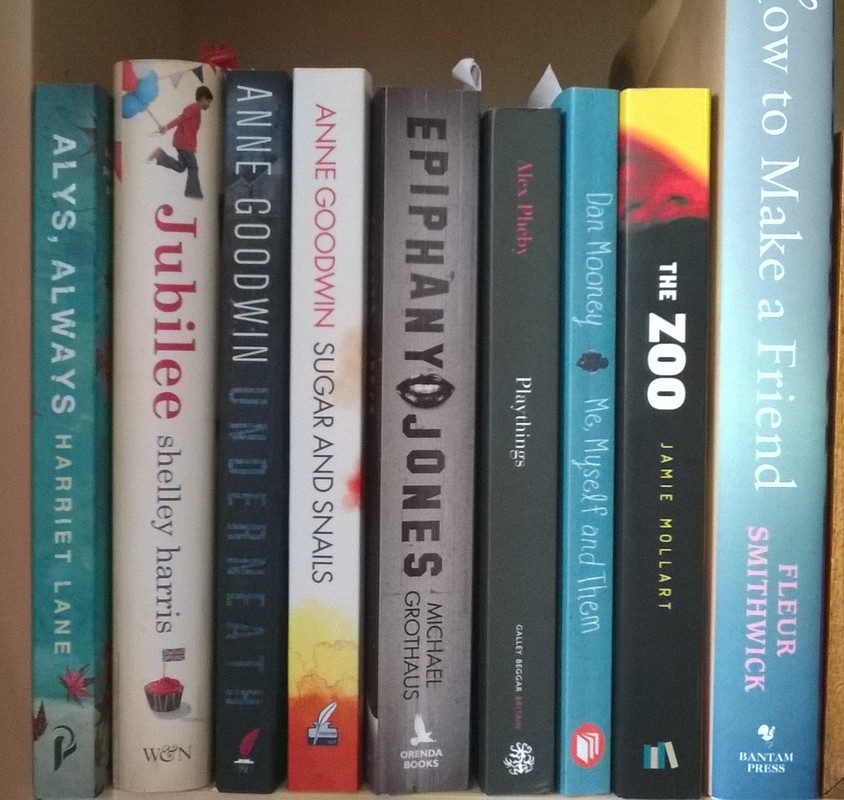

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed