Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

9 fictional psychologists and psychological therapists: 5. The Other Side of You by Salley Vickers29/1/2014  The Other Side of You is about an encounter between two people; an encounter that, in different ways, saves both their lives. A serious suicide attempt has brought Elizabeth Cruikshank to the hospital where David McBride works as a psychoanalytically orientated psychiatrist. Shrouded in her despair, David is unable to make any progress with his patient until, recalling a painting by Caravaggio, he acknowledges their mutual stumbling humanity. In the course of a mammoth therapy session, Elizabeth shares her story of the love lost and found and lost again that led to her attempt to take her own life.

4 Comments

Many moons ago, when I still liked to travel, I took a long haul flight with Aeroflot that meant a stopover of several hours at Moscow airport. This was back in the days of the Iron Curtain but, apart from not being allowed out to explore, they treated us well, with a room to lie down in after a hearty breakfast. What I remember most, however, was having my stereotypes confirmed about life under communism: none of the staff who took care of us ever smiled. Having been back to the city as a proper tourist and ventured beyond the airport and the superficiality of first impressions, I wouldn't say that was necessarily characteristic of the nation (at least not after a few vodkas). But, according to Lucy Mangan, Bitchy Resting Face is an international affliction. I think I suffer from the opposite, a tendency to look amazingly cheerful (except, perhaps, in my photos) when I'm dying inside.  While the BFR video is tremendous fun, I'm not sure it does much for those afflicted with a genuine disorder, one that unfortunately doesn't generate a lot of laughs. Moebius syndrome is a rare neurological disorder, present at birth in which children are unable to move their faces and being unable to smile is perhaps the least of their problems. I've explored this in my story My Beautiful Smile, first published by Gold Dust and now given another outing. Feel free to read it with what ever facial expression you fancy, but I hope it leaves you with a sense of satisfaction and true gratitude for the ability - if you have it - to smile. And, if you can, wear purple today to mark Moebius Awareness Day.  With another choral concert in the offing, I’ve been conscious recently of my far-from-perfect pitch. Alas, it’s not just musically I’m challenged, but I’ve been struggling with pitching my fiction since an agent workshop around eighteen months ago when I failed dismally to reduce my oeuvre to three sentences, despite my novel being in a not-at-all-desperate state of health. Although I’ve improved dramatically since then, I still find pitching difficult and I’m reassured when bloggers such as Clare O’Dea confirm I’m not alone in this. We don’t all possess the talents of Fay Weldon, coining and promoting advertising slogans like Go to work on an egg alongside writing literary fiction but, in this highly commercialised era, it’s incumbent on writers to try. While a pitch to publishers and agents is not the same as a blurb, and both are distinct from a 140-character enticement to click on the link to a blog post, I’ve learnt a bit on pitching from observing how others market their work on Twitter. It takes a lot of discipline and focus to whittle down the gist of one’s outpourings into a few captivating words. But the ideal pitch isn’t solely down to the writer’s capacity to précis. I don’t think I’m making excuses when I say that some fiction is easier to pitch than others. In an effort to convince you this isn’t only me being precious about my own stuff, I’ll illustrate this but by comparing my Twitter pitches for two of the stories I especially enjoyed from a recent anthology in which my story “A House for the Wazungu” also appears. I’m interested in your views, but I think my first pitch:  Show, don’t tell is something of a cliché in creative writing parlance yet, when I first encountered it, it felt like a paradigm shift. I’d been writing on and off all my life without knowing there were any rules about it, and I embraced this one with gusto. My stories unfolded through a series of scenes, generously seasoned with dialogue and real-world interactions. I aspired to make my colours vivid and my smells pungent and anything masquerading as an information drop became taboo. My writing wasn’t particularly lyrical, and I learned to love cutting the bits that weren’t earning their keep, but overall I wanted the reader to get so close to my characters it was as if they’d taken up residence in their bodies. Even if I never reached my goal of emotional and sensory identification, at least I knew where I was headed. Telling was a cardinal sin and I’d been brought up to steer away from such transgressions. Yet now and then, I found myself wanting to write differently. I’d write an entire short story with only the tiniest pinch of dialogue. Although I was sufficiently fond of these tales to send them out to magazines, I still suspected this wasn’t quite the real thing. More disturbingly, I’d come across patches of telling in novels that I particularly admired. Could it be that this wasn’t wrong after all? Emma Darwin advocates a balance between showing and telling and, through examples, illustrates the differences between good and bad telling. She demonstrates how telling can actually be quite show-y if it’s specific and appropriate to the point of view. Telling isn’t all bad, and it does move the story along. Nevertheless, if telling is to be rehabilitated, it can still be a difficult judgement as to when to use it and how much. Emma points out that the archetypal telling-story is the fairytale (and Clare O’Dea illustrates her wonderful rant against the tyranny of show, don’t tell with examples from Goldilocks and the Three Bears). Something in the rhythms or the narrative voice compensates for the greater psychic distance. I hadn’t seen this post when I wrote My Father’s Love, recently published by Foliate Oak, but it feels like a vindication of a story that is not only 90% tell, but kicks off with something dangerously close to a once-upon-time: When I was a baby in my cradle, or so the story goes, my father gathered up his love for me and fashioned a chalice of burnished gold. He swaddled the chalice in a skein of silk shipped all the way from China and bedded it down in a drawer in his wardrobe where he used to store his cufflinks and bowties. He locked the drawer with a silver key which he dangled from a string around his neck, beneath his shirt, inches from his heart. When it was done, my father smiled, stood back and watched me grow. Perhaps it’s the Hindu storytelling that’s done it, but I’m finding myself increasingly drawn to that style. I’m not sure if it’s another personal paradigm shift or redressing the balance that’s gone too far towards show, but I’m interested to see where it takes me. No doubt I’ll let you know. How about you? What’s your take on showing versus telling? Is it an issue in your reading or writing or are you more concerned about other “rules”?  Any writer submitting her work for publication is supposed to know which genre tick-box it fits. Lucky for me, the rules aren’t so rigid for short stories, as I’ve got a fair few wacky ones I’m not sure how to categorise. My novels are literary-commercial but my short stories vary with the weather and/or my mood. Many are darkly serious, but there’s a smattering of lighter stuff, and sometimes I even raise a laugh. I also have a growing collection of stories which step outside real-world logic, and I don’t know what to call them. Launching my virtual annethologies page at the end of last year was my cue to try and sort them out. The absence of a proper nomenclature didn’t matter so much when there was only Tamsin, the woman who woke up on the morning of her wedding to find her neck had grown as long as her arm. Then Selena started being stalked by unnaturally large footprints and plastic took over Jim’s allotment, not to mention Adam waiting in the wings for his publication call. But now Sam, an ordinary soldier in a time warp where all the wars of the past century are happening simultaneously, has made his debut, I’m duty bound to give more thought to where they all belong. The what-if nature renders these stories speculative, although without an entire alternative scientific or mystical world they don’t qualify as sci-fi or fantasy. For want of an alternative, I’ve been labelling them slipstream, a position midway between speculative and literary, with elements of strangeness and otherworldliness. The word feels right for that gentle slip-sliding into another stream of possibility, another dimensional laid across the familiar world. All fiction asks readers to suspend disbelief to a certain extent; slipstream, as I’m choosing to interpret it, asks them to go a step further, not only to care about made-up characters as if they were real people, but to accept a situation where a single law of physics or history or biology has been turned on its head. By my reckoning, The Time Traveler’s Wife meets slipstream criteria, as does Never Let Me Go, both novels where critics have disagreed over genre. After all, we can’t slip physically back and forth in time to revisit different versions of ourselves (although we all do that in our minds). And, the demonisation of the poor and disadvantaged notwithstanding, people aren’t cloned simply to furnish body parts for the elite. Well, what do you think? Is slipstream a genre with which you are familiar and, if so, what does it mean to you? Does genre matter anyway? And do share your thoughts on Sam’s desire to be a hero if you can.  Published at the beginning of 2013, The Examined Life by Stephen Grosz is a gem of a book about psychoanalysis. Heavy with insight into the human condition while light on the jargon, it’s a most-read for any thoughtful individual, but I’m here to argue its particular value for readers and writers of fiction. If you like stories, I think you’ll be interested in these, and if you’re engaged in producing your own fiction, there’s as much to learn from these tales from the therapist’s couch as from any creative writing textbook. Here are 7 reasons why: 1. It’s unashamedly upbeat about the power of stories. Many psychoanalytic case studies read like stories, but these are especially exquisite. Beautiful prose, tightly structured, these are moral stories without being moralistic, gentle fables in the manner of Aesop and Kipling that leave us pondering the big questions of how to live. Alongside the stories from the consulting room, there’s an examination of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener, and ordinary incidents from the author’s life. Without being heavy handed, he leaves us in no doubt as to the centrality of storytelling, that without our stories we are diminished: [O]ur childhoods leave us in stories … we never found a way to voice, because no-one helped us find the words. When we cannot find a way of telling our story, our story tells us – we dream of these stories, we develop symptoms, or we find ourselves acting in ways we don’t understand. (p10) |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

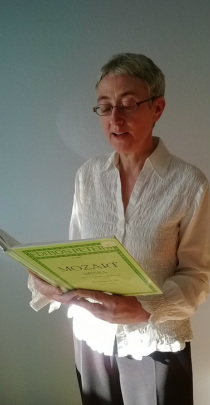

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed