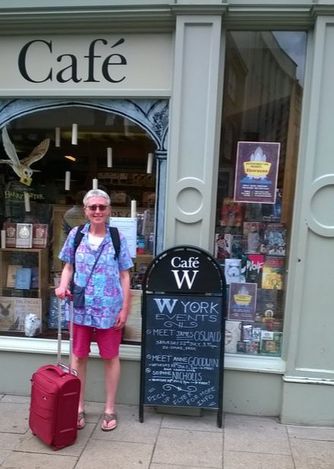

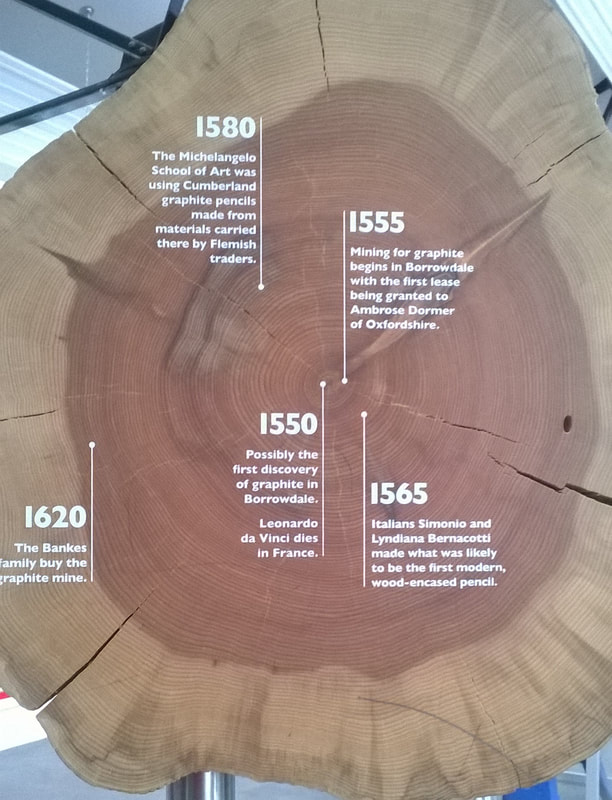

| I’ve been away in Yorkshire on a research trip and returned home thoroughly inspired. But it wasn’t until the fourth and final day that I felt so optimistic. Initially, I was ready to abandon this novel completely and wait for the muse to send me something more plausible. Last week, I mentioned my ambivalence about giving my character kidney failure. But with the setting – a former mill town that’s also a World Heritage Site – I felt on firmer ground. Oh, foolish me! |

Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

5 Comments

Allow me to introduce two recent reads featuring a teenage girl’s sexual awakening with a physically attractive but morally suspect young man, arousing the envy of her less confident suitor. Both novels also emphasise her passion for the place in which she lives: in the first, a derelict asylum in southern England; in the second, the family farm in rural France.

How do boys become men and what happens to those whose journeys go wrong? The first of these novels, set in Scotland, looks at what boys learn from their fathers when the son of a bully goes on to murder his family, apart from his younger son. The second is about a traditional coming-of-age ceremony in South Africa and the physical, psychological and social consequences of a botched circumcision.

As these might be the only non-fiction books I read this year, I was keen to link them. So following on from two novels about dislocation, I’m delighted to share reviews about the opposite. Unfortunately I got myself lost in the first, aimed at readers with a more solid grounding in Greek and Roman antiquities, but managed to navigate better through the second, which is about literally and metaphorically finding and losing our way.

These two novels feature the displacement of people and the unique cultures and environments they left behind. The first introduces us to the remote Scottish island of St Kilda whose depleted population was evacuated to the mainland in 1930. The second links Venice with the Sunderbans in the Bay of Bengal via folklore and cli-fi. Despite their complementary covers, they’re very different books.

In what circumstances is it acceptable for women to abandon their traditional roles? What are the consequences if they should do so ill-advisedly? Although these two novels are set in different times and cultures to my own, they raised questions for me as to how far we can safely step out of line. The first novel pays homage to the forgotten women of Ethiopia who took up arms when the country was invaded by Mussolini’s troops. In the second, set in seventeenth century north Norway, the women have no choice but to do the jobs previously carried out by their menfolk when a storm at sea wipes out most of the male population, only for some to find themselves accused of witchcraft a few years later.

Two novels, written and published almost a century apart, about adolescent boys moonstruck by a slightly older teenager. You don’t have to share the narrators’ fascination to enjoy the novels, although it would probably help! The happenstance of coordinating covers suggests to me the novels are thematically well matched.

Two gripping novels that begin with an unexpected death in the family: in the first, set in Scotland, it’s the main character’s niece; in the second, set in Australia, it’s the protagonist’s brother. In both cases, the evidence points to suicide, until the deceased’s relatives start poking around. Both protagonists discover more than they bargained for but nevertheless benefit from confronting the truth. Both novels are also about male violence and sibling rivalry.

Two novels set in Britain that feature climbing. In the first, it’s the hobby verging on obsession of three of the four main characters, in a homage to Sheffield and the nearby Peak District National Park; in the second, a cli-fi thriller, surmounting the wall is what the narrator and his peers are conscripted to prevent. Thanks to publishers Chatto and Windus and to Faber for my review copies.

I can recommend both of these novels about women whose lives are entangled with that of one man. In the first, three Australian friends are stalked by an unpleasant character when they embark on a long-distance walk. In the second, three Nigerian women have managed their common husband successfully, until he introduces a fourth wife into their home.

I’ve recently been reading two second novels in which a woman sets out to uncover a family’s tragic secret lodged within a large historic house, aided and abetted by a presence that might or might not be a ghost. In the first, the woman and her husband buy a crumbling manor house as a weekend retreat from London; in the second, the woman is employed in the London mansion as carer for a man who can’t throw anything away. Both have strong voices and characterisation, with beautiful descriptions, but differ sufficiently that you could happily read both. For other novels about mysterious houses see Fell by Jenn Ashworth and post What’s haunting these houses?

Has my country always been this conflicted, or is the second decade of the twenty-first century a particularly sour time for England? Can fiction help us understand our current disaffected state? If so, these two very different novels – the first a gentle exploration of fear of difference among the largely white population; the second addressing the attractions of Islamic State to young people of South Asian descent, and its more violent repercussions – might help.

If we leave home at eighteen, it’s often to a particular kind of institution. For me, as for Selin in The Idiot, that means university; for Billy Lynn, as for many young working-class adults who are less academically inclined, it’s the military. While, as Selin discovers, universities encourage questioning, not all questions are received with equal relish. On the other hand, as Billy learns, the army might discourage independent thought, it can’t prevent his wondering. Will these young people find the answers they’re looking for? Read on!

With my shameful disregard for non-fiction, I glean many of my facts from fiction. So I was delighted to receive advance copies of two debut novels published this month that I hoped would extend my knowledge of shameful periods of Australian and Scottish history that still resonate to this day. Lucy Treloar and Mhairead McLeod have woven engaging stories around historical facts of land appropriation in the 19th century. Although my reviews focus more on the psychological aspects, these novels clearly articulate the socio-political context of the European colonisation of Australia in Salt Creek and the Highland Clearances in The False Men.

I didn’t expect to pair these two novels. I’d already begun reading another Second World War novel to accompany The Sixteen Trees of the Somme, and The Angel in The Stone was going to wait for another novel on mental health. But the latter seemed a good fit for the latest flash fiction challenge and, as I’ve mentioned recently, it’s fun to find unexpected links. Both these novels feature families across three generations; address conflict between brothers; are wholly or partly set in Scotland; and showcase the characters’ musical tastes. Both fictional families have hidden some of their history from the younger generation in a manner that makes life just that little bit harder. Read on, and see what you think.

Allow me to introduce you to two novels looking back on Ireland’s recent history through the eyes of a man whose life has been limited by secrets, subterfuge and hypocrisy.

Let’s take a look at a couple of debut novels with some fine evocations of the natural world and a strong sense of place published by small independent presses based in Scotland.

For my first post of meteorological autumn, I bring you two novels with a strong sense of season and climate. But what particularly connects them is their explorations of how conflicting attachments to place risks fragmenting family life. The first takes us from England to Australia, with a brief visit to India, and the second back and forth between Canada and the USA, so between them these novels cover a large proportion of the English-speaking world.

Like Workington and Barrow, Morecambe is a small, slightly rundown, coastal town in north-west England to which I have personal connections: my parents lived there for many years and, coincidentally, one of my good friends, whom I met in Cairo, has a house overlooking the bay which, for a short while, she ran as a guesthouse. Although I don’t refer to it by name, it’s also one of the settings, along with Nottingham, for my forthcoming novel, Underneath. So when I discovered Owl Song at Dawn was set in Morecambe, I was keen to read it. I was even happier to be offered a slot on the blog tour when the author agreed to write a post on the setting. I hope you enjoy Emma Claire Sweeney’s piece as much as I did. My mini review follows at the end. |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

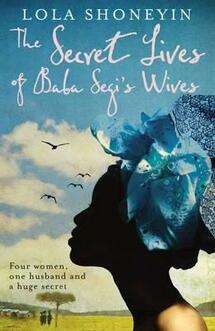

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed