Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

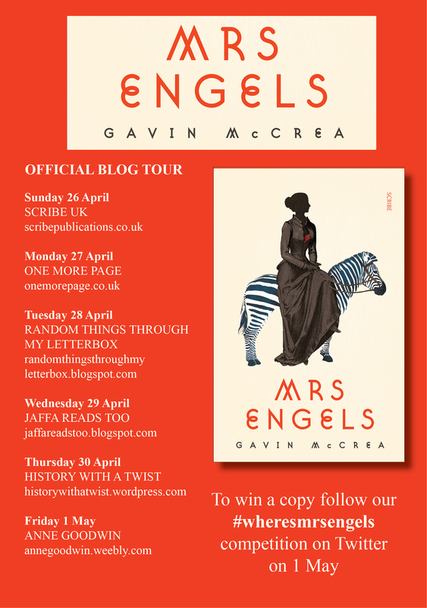

Following last month’s post on reading for my reviews, I thought I’d share a little of what I do with them once they’re written. Obviously the appear on Annecdotal, but where else? Well, there’s Goodreads which drew me in initially as an attractive way of keeping tabs on my reading. Another way I keep track is through the listings on my reading and reviews page although, because I’m better at remembering the book than the author, the alphabetical ordering doesn’t always help. Then there’s Twitter (along with the myriad hashtag days) which can generate some lively discussion and Facebook which, probably because I still don’t know how to work it properly, tends not to. Also, because most of the books I review come from the publishers, I tweet and email them the link; if it’s from one of the Hachette companies involved in Bookbridgr, I also log the review there. That’s quite a lot of admin, but there’s still one glaring omission that troubles me somewhat; it’s not exactly the elephant in the room, but the huge empty space where that elephant should be.

12 Comments

Fifteen-year-old Jules is taken in by the cool kids at the arty Spirit-in-the-Woods summer camp, or perhaps, this being the early 70s they’d be the trendy set. (Don’t ask me, I only lived through that period.) Whatever (which they definitely didn’t say back then, or certainly not in a flippant way), they are so in love with irony they adopt the name “the interestings”, not registering that even their irony can be ironic. The camp is idyllic, indulging the teenagers to believe in their talent. Jules, from a small town with small-town ambitions, still grieving her father’s death less than a year before, leaves convinced she can make it as an actor (or would it have been an actress back then?).  Fleeing from Leeds to Brighton after breaking up with his over-possessive lover, Jem, Luke rents a tiny house caught in a time warp from the 60s. His landlord is the elderly philanthropist Joss Grand who, despite ill-health, hasn’t totally shed the legacy of his years lording over the Brighton underworld, with his sadistic sidekick, Jacky Nye. Luke is a former journalist with an agent waiting for him to pitch the true-crime story that will make his name. When Luke learns that Jacky Nye was strangled and thrown into the sea back in the late 60s, his murderer never found, he is convinced Joss Grand, despite a strong alibi, must have been involved. Convinced the opportunity outweighs the risk, both to him and his friends, Luke can’t let go of what appears to be the perfect scoop, and arranges to interview the prickly Mr Grand. Already under threat from his unstable ex-partner, as Luke is drawn deeper into the murder mystery, we wonder if he might have been wiser to leave the past alone.  Sergio Scorpioni is the president of Vallerosa, a tiny land-locked country of rich red earth and steep ravines. With polling day imminent, Sergio is nervous, despite the fact that, in an elected dictatorship in which every job from postman to government minister is passed from father to son, his re-election is more or less confirmed. Lizzie Holmesworth is a well-meaning middle-class British student, keen to undertake some voluntary work with those less fortunate than herself as part of the Duke of Edinburgh’s award scheme. Arriving in Vallerosa on the overnight freight train – the country’s primary communication channel with the rest of Europe – Lizzie is overwhelmed by the beauty of her surroundings and the warmth of her welcome. What she doesn’t realise until much later is that the letter that preceded her, mentioning the Duke of Edinburgh’s award and bearing the image of Queen Elizabeth II on its stamp, has led them to expect a royal visitor who will endorse the government’s legitimately at this uncertain time. Reluctantly, she agrees to the president’s request that she continue with the pretence although, the more she learns about the country, the more she’s taken with the peacefulness of the lifestyle and the less she feels she has to offer.  Is a background in psychology an asset when it comes to writing fiction? How easy is it to combine a scientific approach to the mind with one embedded in the imagination? I decided to ask professional psychologists who are also published novelists how they do it. I’m delighted to welcome Voula Grand to Annecdotal for the first post in this series. As a business psychologist, I advise large corporations on executive performance and leadership development. My work has some similarities to sports psychology, as I’m hired to increase the success of executives who are already performing at the top of their game; so doing even better is down to subtle refinements of leadership that can make a powerful impact on business results. In order to help my clients, I am widely trained in an extensive range of human change methods and techniques, from traditional therapies and psychological frameworks to the contemporary methods of positive psychology that impact the dynamics of thoughts, feelings and behaviours. Psychological resilience is a hot topic in corporate psychology at the moment, and I am experienced in the techniques that promote this. I spend my working days in close communication with executives, either one on one or within their teams. Understanding the organisational context is important, and I need a good business grasp of the strategic aims, culture and goals of the client company, and of the broader corporate world.  Kate Hamer’s debut novel reminds me of a conversation a friend had with her pre-teen daughter after a relative’s baby had died. “It’s the worst thing imaginable to lose a child,” said my friend. “No,” insisted her daughter. “It’s much much worse to lose a parent.” The Girl in the Red Coat doesn’t ask us to choose: it explores the nightmare scenario of a child going missing from the perspectives of both the mother and the girl. Carmel Wakeford is eight when she becomes separated from her mother at a children’s storytelling festival (at which I think I detected a cameo role for the doyenne of children’s fiction, Jacqueline Wilson). A man who claims to be her estranged grandfather tells her her mother has been taken to hospital after an accident and that he’ll look after her now. A few days later, he gives her the devastating news that her mother is dead and her father wants her to remain with her grandfather. She’s taken to America to a new life on the fringes of society, moving between evangelical churches, where Carmel’s supposed “healing hands” are much in demand.  A man who’s always been suspicious of computers goes to buy an iPad. Unfortunately, he’s also highly suspicious of people, especially the white-shirts who seem intent to frustrate him with paperwork. The ensuing argument almost has him evicted from the shop. Meet Ove: a crotchety old geezer who’s thwarted every way he turns. He can’t even be left in peace to end his own life. I’m always intrigued when a novel worms its way so deeply under my skin I start behaving like the main character. So what if this was a million-copy bestseller, I wasn’t going to trust a writer who reckons the first thing I need to know is the age of his main character (fifty-nine), closely followed by the kind of car he drives (a Saab). To hell with the respectful approach I’d outlined in my post on my reading for reviews, this one was going to be a meditation on the minutiae of getting it wrong. Never mind that, in going to test drive a new car (not a Saab) recently, my husband and I found ourselves embroiled in a disagreement similar to the one Ove engenders in the computer shop. My grumpiness was nothing to do with me, or even the fact that I was reading the novel while still enraged about the result of the recent election.  The war is barely a year old when James is shot down on his first bombing mission. Incarcerated in a POW camp, he vows to use his time productively. Instead of digging escape tunnels from which he’d inevitably be recaptured, James dedicates himself to a detailed study of a pair of redstarts nesting beyond the barbed wire. He records his observations in a notebook and in letters home to his wife. Yet the only person who really seems to understand his passion is the camp commandant. Only six months married before James was summoned to fight for his country, Rose is bored by her husband’s letters, barely able to bring herself to open them, let alone reply. Alone in a tiny cottage on the tip of the Ashdown Forest not far from where she grew up, she spends her time roaming with her dog and patrolling as an ARP warden to safeguard the blackout. She’s wondered about her loneliness for some time: at first she thought it was missing James but now it seems an existential condition. And she’s found a way to soothe it in her secret meetings with Toby, on sick leave from the war. Then James’s elder sister, Enid, is bombed out of her London flat and, with nowhere else to go, she foists herself upon Rose. With her own guilty secret, Enid isn’t the best of houseguests, while Rose is far from the perfect host. The women have more in common than they think, but their different loyalties to James prevents them becoming friends.  It’s 1925 and one can’t help wondering (worrying) how such a sweet ten-year-old as Teddy, entranced more by nature than the prospect of wielding a catapult, will cope with boarding school, let alone the war that neither he, nor the adults around him, could possibly foresee. Yet I didn’t feel totally engaged with him and his family until introduced to his dreadful daughter, Viola, with her half-baked hippy ideals (that are as much an opportunity to spout one of the longest words in the English language – anti-establishmentarianism – as to challenge her father). But since this is a novel in which time is not linear, but moves back and forth across the years, I didn’t have too long to wait. Delightful as Viola’s character is, her shallow idealism is hardly original (see my review of Love and Fallout for another young woman who embraces a cause as a means of forging her own identity), but Kate Atkinson is too proficient a writer to leave it at that. Viola has much more in common with the pre-war version of her father than she realises (when he roamed through Europe working on the land), and a stronger rationale for her angry sense of victimhood than the reader appreciates, until approaching the end.  I am sorry. I can not invite you home for Christmas because I am Irish and my family is mad. In 1980, in County Clare, ten-year-old Hanna is feeling the tension between her parents’ different backgrounds as her elder brother, Dan, announces he wants to be a priest. Eleven years later, Dan is most definitely not a priest, living with his girlfriend on the fringes of the New York art and gay scenes. Six years after that, in County Limerick, the eldest of the Madigan children, Constance, is a plump stay-at-home mother of three. Then it’s 2002 and we get to occupy the head of Emmet, an aid worker in Mali, learning (like Mrs Engels) the complexity of running a house with “staff” (p109): You could be saving lives all day and be undone at the end of it by a plate of beans and bad lard. Literally saving lives. Because wars you can do, and famines you can do and floods are relatively easy, but no one survives when the cook scratches his arse and then decides not to bother washing his hands.  Tom Berry is a forester in northern Canada. He’s a decent chap, drawn to the wilderness, trying to do right by his family and his employees. But he doesn’t really do feelings, and feelings are what he needs to guide him when his grown-up son, Curtis, is stuck in despair about some woman. Instead of listening, the ever-practical Tom sets to work on repairing a leaking tap. At nineteen, Tom wasn’t ready for fatherhood. Four years on, he wasn’t ready for his unstable wife to leave him with young Curtis and his four-month-old sister, Erin. But he thinks he’s done okay, raising them to be independent, teaching them the countryside survival skills he values. It irks him that Curtis has never been much of a hunter, that teenage Erin now prefers to keep to her room. But he accepts that his kids are reaching the age when they’ll no longer needed him, when he’ll be free to retreat to the cabin in the forest he’s always dreamt of; perhaps, if he’s lucky, his part-time girlfriend, Carolina, will join him there.  A strange young man emerges from the ocean in 1980s South Africa. Neither black nor white but a bit of both, with the blue tinge of the coelacanth thrown in, Jimfish is a problem for a country in which people are “coralled in a separate ethnic enclosures, colour-coded for ease of identification and tightly controlled” (p1). Nevertheless, he finds employment as a gardener under the tutelage of Soviet Malala until he’s caught “as tightly tangled as the tendrils of the strangler fig” (p7) with the police sergeant’s daughter, Lunamiel, and has to flee the country. His attempts to stay on “the right side of history” take him on an epic journey through Africa into Eastern Europe and back again. Everywhere he goes he encounters carnage and confusion (p123): The more he saw of the world, the less he understood. Worse still, what he did understand was so crazy, so cruel, that none of the lessons of his old teacher Soviet Malala seemed to apply; not rage nor the many sides of history, neither the lumpenproletariat, nor the settler entity.

|

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed