Delightful as Viola’s character is, her shallow idealism is hardly original (see my review of Love and Fallout for another young woman who embraces a cause as a means of forging her own identity), but Kate Atkinson is too proficient a writer to leave it at that. Viola has much more in common with the pre-war version of her father than she realises (when he roamed through Europe working on the land), and a stronger rationale for her angry sense of victimhood than the reader appreciates, until approaching the end.

As with the debut novel The Mountain Can Wait, published on the same day, this is about the difficulty of communicating feelings, especially across the generations and even more so when the older generation values buttoned-up stoicism (as, for example, in Everything I Never Told You) while the younger believes in “letting it all hang out”. Teddy’s medals for bravery are all but forgotten in his move into supported housing for the elderly. Yet even during the war, on leave from the airbase, Nancy, the woman who will be his wife, doesn’t want to hear about the mechanics of bombing. But Teddy’s generation isn’t the only one whose heroics are neglected; his Aunt Izzie is perceived by the entire family as flighty and irresponsible, yet she too was recognised for her service, in her case in a field hospital not far from the mud of the trenches in what they then called the Great War.

In an early chapter, Aunt Izzie questions the young Teddy in a manner that writers will recognise: she’s writing a book based on the adventures of a young boy (that could be taken as Kate Atkinson’s homage to Richmal Crompton). As with Margaret Atwood’s, The Blind Assassin, excerpts from this book show the characters in a different light, especially at the end of the novel. But Izzie is not the only writer; Viola also finds success – if not happiness, nor her father’s approval – by fictionalising her life. And it’s not only the published novelists who play God in this manner: the airmen write upbeat letters to be sent to their families should they fail to return from a mission. Yet it’s in a lie she tells her therapist that Viola points to another theme of the novel (p312):

because that sounded infinitely more interesting than the cold, damp truth of mutual indifference. As you got older and time went on, you realised that the distinction between truth and fiction didn’t really matter because eventually everything disappeared into the soupy, amnesiac mess of history. Personal or political, it made no difference.

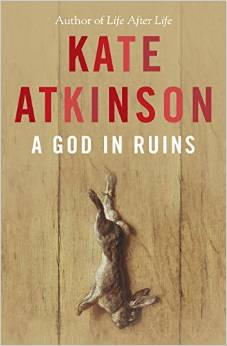

I’ve enjoyed Kate Atkinson’s writing since her debut Behind the Scenes at the Museum (although I missed her most recent, the Costa winning Life after Life to which A God in Ruins is a companion), but this is definitely her best. A triumph of storytelling, pondering life’s deep questions through engaging characters and page-turning prose; thanks to Doubleday for my advance proof copy.

This is the fourth of my reviews of six novels published today (7th May). If you missed The Green Road, The Mountain Can Wait or Jimfish, you can find them here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed