Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

A bunch of teenagers lounge about in a country house on a remote island. They form gangs, their leaders battling for supremacy, though, with nurses and teachers standing on the sidelines, it’s not quite Lord of the Flies. Drugs also help to maintain order, in the form of the nightly “vitamins” that the narrator, Toby, secretes in his bedpost, leaving him free to wander through the house while the others sleep. Although, when he witnesses one of the boys being taken at night to the top-floor sanatorium, he almost wishes he’d stayed in bed. Everyone knows why they’ve been wrenched from their families to live in the Death House yet, through a mixture of boredom, bravado and emotional distancing, they try to defend themselves against the truth. Blood tests have shown that their defective genes have been activated; the adults are merely keeping watch for the signs of their sickness to show.

6 Comments

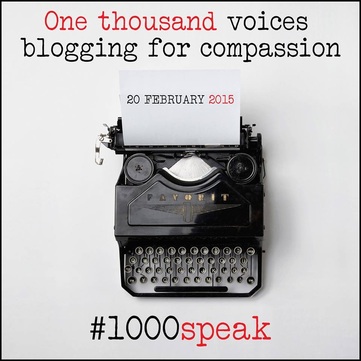

Three days after her sixteenth birthday, Lydia Lee is dead. As with the Mormon family in A Song for Issy Bradley, the different ways in which her parents and siblings, older brother Nath and younger sister Hannah, react to the loss brings further hurt to them all. The favourite child of both parents, it seems that Lydia has held them together; her absence reveals and widens the cracks in the family system. The parents met at Harvard: James a postgraduate student delivering his first ever lecture on that great American archetype, the cowboy; Marilyn an undergraduate determined to make it in the male-dominated world of medicine. Pregnancy and marriage puts paid to her ambitions as they move to small-town Ohio where James has been offered a teaching post. Chillingly, their marriage would be illegal in some States: James is the only son of Chinese immigrants and, in 1958, interracial relationships are taboo.  When I began this series of fictional therapists, I never imagined I’d encounter one who served, three days a year, as receptionist for a “chromotherapist” in the same office. When I wrote the guidelines for creating a credible fictional therapist, it didn’t occur to me to caution against installing a therapist in a building with such inadequate toilet facilities that clients, if caught short, would be obliged to relieve themselves into a used takeaway carton in a screened-off area of the office. But, despite her degrees in clinical psychology and, surprisingly, social work, I doubt that anyone would look to Miranda July’s creation for an insight into the machinations of psychotherapy and, while I found Ruth-Anne mildly amusing, she wasn’t as funny as the Lacanian analyst in The House of Sleep, so let’s dispense with her and move on to the more interesting aspects of this quirky debut novel. Cheryl Glickman is a single woman in her early 40s, stuck in a rut as peculiar as you’re ever likely to find, yet one that resonates with more conventional lives. Living alone, she’s devised an ingenious, if obsessional, system for minimising housework and the despair that can ensue when the mess gets out of hand (p21):  Today’s the day that the internet is going to zing with antidotes to the mammoth cruelty and indifference to suffering that exists in this world. The 1000 Voices Speak for Compassion blogathon, launched by Yvonne Spence just over a month ago, has rocketed through the airwaves (or do I mean fibre-optic cables?), enthusing a galaxy of bloggers and tweeters to join in. As a warmup, Charli Mills compiled a virtual anthology of the Carrot Ranchers’ compassion-themed 99-word stories. Mine focused on compassion within marriage (after all, it was Valentine’s Day when I posted) and the self-compassion that’s needed for compassion for others to thrive. My contribution to the 1000 Voices is to elaborate the ideas behind that flash. It might seem contradictory to focus on the self when the genesis of this movement was to combat the despair at an apparent lack of compassion for others. Yet one of the examples that Charli gave in her post introducing the compassion prompt made me think about how people can find compassion for others difficult because they haven’t experienced sufficient compassion themselves. Even if compassion doesn’t require them to do anything, it might feel too big a burden to take on, especially if they’ve been shackled with caring for others when they were desperately in need of care themselves.  Born “at the end of the world”, Lalla has led a sheltered life, protected by her father’s wealth and her mother’s constant vigilance from the worst extremities of post-apocalyptic London. Although deprived by today’s standards, relative to the conditions of the stateless squatters in the British Museum, which she visits with her mother every day in lieu of school, she lives in luxury, with locks on the door of their flat and the prospect of tinned peaches for her birthday dinner. Her father, Michael, visits intermittently, spending most of his time procuring goods that will stock the ship he has purchased for her salvation and that of another 500 worthy souls. On her sixteenth birthday, after Lalla’s mother is fatally wounded by a shot through the window of their flat, Michael takes his daughter to set sail for a better life. Initially, Lalla’s unhappiness is attributed to her grief at her mother’s death, exacerbated by her father’s insistence that those on board should renounce all ties to the past. Even her developing passion for football-coach Tom cannot prevent her unease at what is happening. The other passengers, selected on the basis of their generosity to others or resistance to the military regime, see Michael as a Messiah figure and are increasingly frustrated by his daughter’s apparent rejection of his largesse.  Where were you when you heard the news of the planes crashing into the twin towers of the World Trade Center? I was at work, trying to squeeze a month’s worth of tasks from my to-do list into the remaining forty-eight hours before I left for a three-week holiday. One of my colleagues had heard the news on the radio during a ten-minute break between clients, but it didn’t make much of an impression on me until I got home and saw the footage on TV. So it wasn’t my story. Another of my colleagues was bound for a conference in New York, on a plane that got diverted to Canada. He came back with a tale to tell about the kindness of strangers, of sleeping like a refugee in a sports hall, and missing out on what might have been his only opportunity to attend a conference abroad. His story was bigger than mine, but still not much of a 9/11 survival story. In Richard Bausch’s Before, During, After, Michael Faulk is waking up with a hangover in a hotel in New York, deciding against breakfasting at the top of the towers before attending his cousin’s wedding. His fiancée, Natasha Barrett, is on a Jamaican beach holiday with one of her friends, frantically trying to find out if Michael is alive. This is their story. So we’re at that time of the year again when a certain type of bloke stops giving his partner slaps and punches, and presents her with a bunch of painted carnations from the petrol station instead. Cynical, moi? After blogging this time last year about how a touch of romance can make a dark story a little lighter or render a speculative setting more credible, I thought I’d look back over my recent reviews for novels with the kind of literary coupling I’d enjoy. After all, there’s a romantic plotline in my forthcoming novel, Sugar and Snails, even if it does kick off with a couple at the point of breakup, and the only Valentine cards are those sent to an extremely embarrassed teen.

Today’s post features two unusual debut novels, both by young men borrowing the voices of other young men struggling to make their way in the modern world. Although these novels are very different, I’ve coupled them because they’re both slightly offbeat first-person accounts of young men trying to do good, with a touch of humour, and, like with The Winter War, the characters are fully rounded through being depicted, not just at play but also, at work. Matt is a young schoolteacher from Birmingham (UK), sometime boyfriend of Annabel and Franz von Papen (the German chancellor who survived the Night of the Long Knives) obsessive. Although his subject is history, he seems detached from his own background, seemingly having no significant relationships other than those forged within the novel or immediately prior to its opening. Enthusiastic about his topic, there is nevertheless a wide gap between his own concept of his merits as a teacher and that of his employers; some dubious professional choices lead to him eventually being grateful to procure a job defumigating shoes in a bowling alley.  If I say this is a novel about a house, and the secrets it harbours, would that give the impression it’s about bricks and mortar (and, in this case, a lot of wood) rather than people? But I want you to avoid the disorientation I experienced for the first few chapters as I tried to grasp hold of the plot. Okay, I thought, eavesdropping on a father’s abrupt phone call from his semi-estranged son, this is a novel about the black sheep of the family, the prodigal son. But no, soon we were fast forwarding twenty years, with Red, the father, suffering a heart murmur, and Abby, the mother, on the verge of dementia, into a story about getting to grips with old age. But then the tail veers off into the story of Red’s father, Junior Whitshank, a perfectionist carpenter who built the family house on commission long before he could have afforded to live in it, and was more devoted to it than he was to his wife. It took another diversion into a surprise revelation about the youngest of Red and Abby’s four children before I could allow myself to give up my search for the plot and enjoy the ride. Like the cruising teenagers depicted on the cover, you don’t read this novel to get to a particular destination (although it does have an ending consistent with both the prodigal son and ageing parents non-plots) but to enjoy the company along the way.  The Haitian earthquake of 2010 makes an unusual setting for a romantic comedy, but this novel manages to beautifully balance the devastating impact of the unexpected seismic event alongside celebrating bonds of affection and the resilience of the human spirit. A love triangle between twenty-year-old artist Natasha Robert; her new husband, the president, forty years her senior; and Alain, the lover she has abandoned in the hope of escaping the confines of her native country. The novel opens with a bang in the rubble of the airport, with the reader sharing Natasha’s initial disorientation; only moments before, she was climbing the steps to the plane that was to take her and her husband to a better life in Italy.  Ana Martí, society correspondent for La Vanguardia, is delighted when her editor assigns her to her first serious crime story. Reluctantly, the police allow her to shadow their investigation into the murder of wealthy widow, Mariona Sobrerroca. But this is 1952 and, under Franco’s fascist dictatorship, police brutality is rife and the press heavily censored. When Ana discovers some letters suggesting that the murder isn’t the relatively straightforward result of an interrupted burglary, she submits a story not entirely in keeping with the official version of events. With the assistance of her cousin, Beatriz, an unemployed professor of Iberian dialect, Ana risks her life to unravel a conspiracy perpetrated by the city’s corrupt elite.  As some of my reviews will testify (e.g. My Real Children; Indigo; Hidden Knowledge), I can feel disorientated when a novel fails to unfold according to my expectations. But isn’t that often the case initially when we come to read fiction? Unless it’s ploddingly formulaic there’s an interval, before we settle into both story and style, when we don’t know where we are. Part of the pleasure of opening a new book is that sense that, despite the clues from title, cover and blurb, it could lead us somewhere new. But, as I’ve intimated time and again in my reviews, there needs to be balance between novelty and familiarity, and each of us have our own preferences for where we position ourselves between them. Completing the initial round of my publisher’s edits for my forthcoming novel, Sugar and Snails, I’m reminded of the potential for disorientation I’ve built into the story. My narrator, Diana, has a secret she is unable to share with the reader initially; when you get it, you might look back on what she’s previously told you in a new light. I have to hope I’ve hit a reasonable balance between surprise and security, but I know it won’t work for all. |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed