| When I was growing up, we always had tinned fruit as part of Sunday tea. In those days, I’d never met a peach or a pineapple that didn’t come out of a can. Now that we can get mangoes, papaya and kiwifruit from an ordinary greengrocer, I hadn’t eaten the tinned stuff until I was in hospital last year. I assumed it was a matter of economics and convenience that there was no fresh fruit on the menu. I soon learnt there were medicinal reasons too. Tinned fruit is lower in potassium and you don’t want to overdo the potassium if your kidneys are kaput. |

Welcome

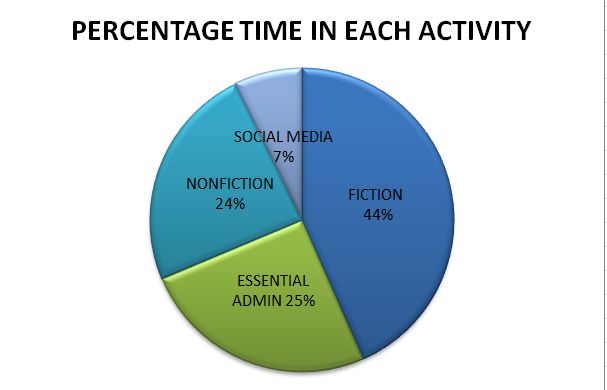

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

4 Comments

Here we have two novels about (celebrity, and the darker side of men whose virtue is part of their fame. In the first, translated from the Italian and set in Rome, an author, teacher and public intellectual can never completely relax into his positive reputation for fear a secret he shared with a former lover will be revealed. In the second, set in New York and rural Tamil Nadu, a young man brought up to believe he’s a living god has to decide whether to continue in the role his father and his followers have given him when he discovers the truth about himself.

I’m struck by the similarities between these two novels, despite being of different genres and set six centuries apart. Both are about men who take pride in their knowledge and intellect yet are blind to the biases that limit their understanding, particularly in relation to women and to physical health. The first is about a nuclear physicist dosing himself with radiation, the second about a young monk’s encounter with the Black Death.

These two recent reads are about marriages under severe strain. In the first, set in the southern USA, a woman turns to a mutual friend when her husband is sentenced to twelve years’ in prison for the crime of being black in the vicinity of a sexual assault. In the second, set in the UK, a family is in crisis as a result of the husband and father’s combat PTSD.

When Inspired Quill, who published my first three books couldn’t find space in this year’s schedule, I considered self-publishing, and, for a whole week in January was convinced I was going with a pricey but prestigious assisted self-publishing outfit until it became clear that, even setting aside printing costs, I’d lose money on Amazon sales unless I ratcheted up the price. Now, of course, with events cancelled for the next several weeks, I feel remarkably lucky to have finally signed with Inspired Quill for May 2021.

Two novels – the first set in Australia, the second in Syria – in which a family marks a milestone. While in the first it’s to celebrate a birthday in a city troubled by nothing more than a refuse workers strike and in the second it’s a burial in a war zone, I found both to be honest and unflinching portrayals of today’s world, and how we got here.

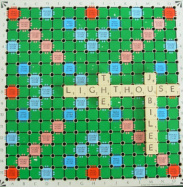

Sorting through the effects of her beloved grandmother, Mariam, shortly after her death, British journalist, Katerina Knight, discovers a wooden spice box containing a journal and stack of handwritten letters. The documents are written in Armenian, a language which neither Katerina nor her mother understands but, on holiday in Cyprus, Katerina meets a handsome young man who offers to translate them. Mariam’s scribbles tell of relatives lost to slaughter and exile in the 1915 Armenian genocide, of a fortuitous rescue by an English couple and a country childhood ending with another lost love. Meanwhile, Gabriel, an elderly Armenian living in Nicosia, exiled a second time with the partitioning of Cyprus into Greek and Turkish sectors, is bemoaning his granddaughter’s engagement to a man from outside the community, perceiving it as a betrayal of her origins, as cultural genocide, although one of his drinking friends advises tolerance (p175-6): ‘Let go of the past, my friend. All that stored up resentment isn’t good for the soul.’ ‘The past is not like water in a toilet bowl. It can’t be flushed away. It’s a septic tank growing more rancid by the day.’ The reader discovers before he does Gabriel’s link to Mariam and Katerina, and from that point the novel is driven by the question of whether these characters will finally connect.  Blackberry and apple crumble Blackberry and apple crumble While I take great pleasure in my ability to harvest fruit and veg from my garden, I don’t get particularly excited about cooking it. As I couldn’t let it go to waste, I’ve been rustling up some strange concoctions of beetroot, courgettes and beans lately and rushing to put them on the table before it gets too cool to dine in the garden. Cordon Bleu it’s not! I’m hoping my response to Charli Mills’ latest flash fiction prompt won’t also come out as a dog’s dinner. Looking for inspiration for my 99-word food story, I turn to the novels on my physical and virtual bookshelves. Consistent with my miserablist inclinations, there’s a dominant theme of the problems that food or its lack can bring. In Shelley Harris’ novel, Jubilee, a boy’s divided loyalties to his white friends and Asian family is played out in his response to the food his mother plans to cook for a street party in 1970s Britain. (You can click on the link to find the quote.) One of the enduring images in Alison Moore’s debut, The Lighthouse, is the way in which, on a catered walking holiday along the Rhine, the main character consistently fails to get the food he has paid for. Although Lewis, the central character in her second novel, He Wants, is forced to endure fewer physical privations, his food is unsatisfying because it’s not what he actually wants. The country house meets friendship betrayed: The Long Shadow by Mark Mills, with fruit for afters27/7/2014  Who says fiction doesn’t change lives? Thanks to Mark Mills, I’ve learnt how to peel bananas from the bottom end, like a monkey. Not that this is a novel about fruit, or animal behaviour (unless you think young boys are like monkeys), but I was grateful for the tip about bananas at a point when the narrative pace seemed to drag. Ben is a scriptwriter aeons away from the big time, a divorced father living in a grotty flat. When a wealthy former schoolmate offers to bankroll his film and install him in his mansion while he does a rewrite, it seems almost too good to be true. As, indeed, it is, but Ben is so seduced by his good fortune and Victor so skilled at manipulation, it takes some time for him to figure out exactly how and why. When he does, it’s immensely satisfying: country house meets poisonous friendship (and so refreshing to have the latter portrayed from the male point of view for a change) seasoned with boys’ games along the lines of Lord of the Flies, the resolution encompasses envy, childhood neglect, rivalry and turning a blind eye to painful truths in a psychologically astute way. I must confess, however, I appreciated this more in retrospect and there were moments across the first 200 pages when I was tempted to give up.  For most of my 20s I lived with a man who had spent his early years in a village in Punjab. His father, despite being permanently settled in the UK and not having a huge amount of surplus cash, was determined to buy a house with a plot of land for each of his sons “back home”. In his mind, it was worth going without in his current place of residence to invest in the place where his family had lived for generations. I was reminded of this on reading Johanna Lane’s debut novel, Black Lake. An Indian immigrant might seem worlds away from of a country gentleman in Donegal, yet my ex-boyfriend’s father and Irish patriarch, John Campbell, shared a similar tenacious attachment to their ancestral lands. While one moved thousands of miles away and the other made an uncomfortable compromise to enable him to stay, both their identities were rooted in the soil of their homelands.  Approaching a big town or city by train is like entering a stately home through the back door. The tracks skirt scrapyards and dustbins, edge past tumbledown housing with washing flapping on the line. On a train journey in Britain, you might also notice a patch of open ground that resembles neither a demolition site or school playing field. It looks as if several gardens have been detached from their houses and brought together, except that here, instead of lawns and shrubberies, you’ll see rackety sheds and beanpoles, and row upon row of that green stuff you’ve plucked from supermarket shelves. Allotments have been part of the British landscape for around 200 years. The Allotments Act of 1925 gave local authorities a statutory responsibility to protect the land on which the urban poor might grow their own food. In the middle of the last century, they tended to be the preserve of the flat-capped working-class male; he would grow the carrots and spuds and her indoors would cook them. Later, families and foodies contributed to an allotment revival. Like the community of writers, allotment holders are highly supportive bunch: when I started mine, the old hands couldn’t resist stopping by to tell us what we were doing wrong. Now I do my growing in my own garden, but I still rely on the lessons – and repeat the same mistakes, according to my husband – that I learned back then. And, because writing is like gardening, I’ve written allotments into a couple of my short stories. Plastic, just published by The Treacle Well, pays homage to the allotment tradition while raising concerns about the threat of pollution to the soil on which we all depend. Albarello di Sarzana is a lighter read celebrating the communal side of allotments and the wonder of growing one’s food. In Stealing the Show from Nature, a gardening project on a much larger scale provides the backdrop to a rough patch in a marriage. It won’t be long before I’m sowing seeds in the greenhouse again. In the meantime, it’s great to celebrate last year’s garden harvest along with this writerly one. Please share your thoughts below.  Reviewing my latest interview with a debut novelist, I’m wondering how come I keep selecting novels where the protagonist goes hungry. Is this about my drive to connect writing with my garden produce, or the authors’ own obsession with food? As I tuck in five-year-old Pea alongside twelve-year-old Haoua, I’m hoping the grown-up protagonists of the other novels, like the anxious but hands-off adults in The Night Rainbow, will offer her something to eat. Yet, somehow, I don't think Futh will notice that Pea’s mother’s forgotten to feed her, and I’m really not sure how patient Grace would be with small children, but perhaps Satish could get his mother to rustle up some party food. I’ve read some of Pea’s interesting thoughts on food, but does she like chakli? I suppose he’d be willing to try anything, as long as Margot goes first. Nutrition isn’t only a biological necessity; in life, as in novels, food symbolises care, and so fiddling around with it serves to make life harder for the protagonists. Writers sacrifice the desires of their characters in favour of the reader’s love of narrative tension. On one level, the thwarting of even imaginary people seems harsh, yet one of the things that struck me across the five Q&A’s I’ve completed so far was the authors’ empathy for their creations. Claire King told me she loved the way I could make myself feel emotions with fiction I had written myself and, over on The Literary Sofa, she highlighted one consequence of writing from a child’s point of view as the need for plenty of tissues. Shelley Harris was so wrapped up in her character’s psyche that she chose

his career unconsciously, as he would have done himself. The impetus for Gavin Weston’s novel was his concern about the fate of a girl his family had sponsored; its completion has driven him to take a more active role in relation to the practice of child marriage by becoming an ambassador for FORWARD. While we might expect writers to empathise with their child characters and/or those who have been treated unjustly, their empathy for their more prickly protagonists was also apparent:  The work and pensions secretary, Iain Duncan Smith, claims he can live like common people on benefits of £53 a week, 15% of median earnings, apparently. Well, obviously that's a red rag to a journalist who will find very good copy in showing it just can't be done (Lucy Mangan) and would prove nothing if it could (Zoe Williams: what's one week of discomfort in the midst of fifty-two in relative luxury?). Might also have been a red rag to this blogger, given that I live in the computer, walk everywhere and my favourite food is lentils. I thought I might manage it if I pretended I wanted to do the 5:2 diet and the last two days were fast days, until I remembered that I wouldn't be able to use the computer I bought back in January because, at a cost of 13 weeks' benefits, I couldn't have afforded it. More disturbing, however, than these glib comments that suggest our politicians have a limited understanding of living on the breadline, is the continual drip feed of misinformation about the poor that comes from official channels. The DWP could soon start running masterclasses in point of view and the unreliable narrator. Perhaps that would be a healthier way of managing the debt than demonising a group of people who are already down: Fraud, which accounts for less than 1% of the overall benefits bill, was

Now that I’ve uploaded a second interview, it seems time for a proper launch of the author interviews section of annethology. Thanks to Alison and Shelley for your thoughtful responses to my amateur questions and I hope that others find the interviews an interesting and enlightening read. While it might be premature to look for patterns across such a small sample, it would be a pity to throw up the opportunity to give it a try. Blame it on Shelley for introducing the idea of the unconscious, but was there a reason for kicking off with these two particular authors and their books? Two first novels by female writers, albeit very different in tone and style, yet both featuring middle-aged men haunted by the past. Books I’d enjoyed reading, and that had also intrigued me, made me think. Books that had done well in the marketplace, so other readers and novice writers might be curious too. I wasn’t thinking much deeper than that when I contacted the authors, unsure how willing they’d be to take part. |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed