While it might be premature to look for patterns across such a small sample, it would be a pity to throw up the opportunity to give it a try. Blame it on Shelley for introducing the idea of the unconscious, but was there a reason for kicking off with these two particular authors and their books? Two first novels by female writers, albeit very different in tone and style, yet both featuring middle-aged men haunted by the past. Books I’d enjoyed reading, and that had also intrigued me, made me think. Books that had done well in the marketplace, so other readers and novice writers might be curious too. I wasn’t thinking much deeper than that when I contacted the authors, unsure how willing they’d be to take part.

hardly set them up with a co-counselling session about their childhood traumas. So I pour them both a drink and lead them to the buffet and …

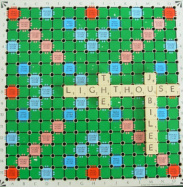

Ah yes, the buffet! Food is often celebrated in literature, but in these novels it can take on a disturbing symbolism. Futh, in The Lighthouse, keeps missing meals, and even the plates of cold meat he is offered seem woefully inadequate, reminiscent of his childhood starved of love:

He wants to eat plenty of meat and carbohydrates, to build up his strength. What he would really like is a big ham sandwich and a homemade cake or pastry, but he only had room in his pockets for a plain roll and a small banana from the buffet. But, he thinks, does he really need any more than that? He could live like this, surely, eating only as much as he really needs to, spending very little, getting by. He sits down in a clearing to eat his lunch and two minutes later it is gone and he feels hungrier than he did when he started. (p120)

As he entered, Satish could hear his mother talking.

‘Of course the children will eat them! Satish loves them. Satish, don’t you love your chakli?’

Satish’s mood flattened. He wished he’d stayed to fight with the girls. Most of all, he wished that Cai had. Instead, his friend was beside him,

and Satish wondered whether there’d be a price to pay for this later on. He answered his mother with careful neutrality: ‘Yeah, I suppose so.’

‘He does not suppose so. He loves them! Takes them from the kitchen all the time when I am making them. They are a lovely snack.’

Miss Bissett gave an exasperated sigh. ‘I’m sure they are lovely,’ she said, ’but they’re not British food, are they? Do let’s remember this is a particularly British celebration.’ (p48)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed