The link is often tenuous when I pair my reviews. But, even when there’s a common theme, it’s unusual for a four-sentence summary to serve both. Heck, even the covers match! Yet, while both brilliant debuts, these are very different novels: the first a near-future cli-fi dystopia; the second a historical novel set at the end of the American Civil War. Read on to see which you’ll pick up first!

Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

A woman lives with her husband on a farm a short distance from a small town. There’s a distance between the partners also but they’re bound by habit and circumstance. When strangers arrive on their land, convention dictates they should chase them away. Instead, a tentative friendship develops, much to their neighbours’ disapproval and it’s not too long before violence ensues.

The link is often tenuous when I pair my reviews. But, even when there’s a common theme, it’s unusual for a four-sentence summary to serve both. Heck, even the covers match! Yet, while both brilliant debuts, these are very different novels: the first a near-future cli-fi dystopia; the second a historical novel set at the end of the American Civil War. Read on to see which you’ll pick up first!

2 Comments

Wolf has lost his wife and, if he doesn’t get his act together, he might lose his daughter, at exactly the moment he needs her most. Michka is losing her words, but is desperate to use those remaining to express her gratitude to a couple she lost touch with in childhood, even though they saved her life. Although I’ve posted a few reviews already this year, these are the first of fiction published in 2021.

If I’ve reviewed any other novels set during the Black Death that swept across Europe in 1348, I’ve forgotten them. These two, published in the UK this summer, are likely to stay in my mind for some time. The first set in Ireland, the second in southern England, they’re very different, although both original in their language and style. And disturbingly topical as we’re catapulted towards an apocalypse – both politically and climatically – of our own.

Too many clergymen, in my experience, set themselves above the hoi polloi, considering themselves above criticism due to their “direct line” to God. I certainly found that in the Catholic response to John Boyne’s novel on sexual abuse in the church. The Reverend Pearson, in The Wind That Lays Waste, set in rural Argentina in the recent past, is guilty of not much more than arrogance, while the Priest in Beastings, set in Cumbria in more God-fearing times, is plain evil. Both men are on a geographical and psychological mission: Pearson’s itinerant evangelism interrupted when his car breaks down, while the Priest leaves his cosy cottage for the Lake District fells on the trail of a runaway girl who knows too many of his secrets.

As if my head weren’t buzzing enough with the enigma of identity, I’ve recently read two translated novels exploring the gap between where the characters come from and where they ended up. In the first, a forty-something German man has given little thought to his origins across the border; in the second, two women, juggle loneliness and language difficulties as they gradually acclimatise to new lives in Australia, far from home.

Two novels about young Asians migrating to the USA: in the first, an Indian man receives a cultural, sexual and political education in New York; in the second, a woman has been stripped of wealth, lover and purpose when she leaves her native Philippines to shack up with relatives in a poor part of California.

If we leave home at eighteen, it’s often to a particular kind of institution. For me, as for Selin in The Idiot, that means university; for Billy Lynn, as for many young working-class adults who are less academically inclined, it’s the military. While, as Selin discovers, universities encourage questioning, not all questions are received with equal relish. On the other hand, as Billy learns, the army might discourage independent thought, it can’t prevent his wondering. Will these young people find the answers they’re looking for? Read on!

How quickly time moves on in politics if I can go, in under three weeks, from hoping that someone will speak out for diversity and social justice to relief we’ve someone who doesn’t come across like an embarrassing uncle (or, in my case, nephew) to negotiate us out of the EU. When the country appears on the brink of Trumpification, I’m grateful for crumbs of sanity wherever they arise. So thank you, Theresa May, for enabling the speedy departure of the chump who gambled his own and his country’s future on a game of dice with his backbenchers, although I feel for the Campbell children having to move house with so little time to pack their toys. As for Andrea Leasdom’s own goal against childless women (of which I’ll have more to say at a later date), all she’s done is demonstrate she’s in politics, not for our collective futures, but for the sake of the genes that will live on in her offspring after her death. What does the working-class child aspire to? In my case, I couldn’t dream of joining a middle-class profession I’d never heard of. Nor, even though I was addicted to writing from the start, did I believe that someone like me could become an author. Books never seemed to be based in the places with which I was familiar: they were set in boarding schools rather than comprehensives; in country houses rather than a small semi-detached; in cities rather than small industrial towns. So how could I resist a novel set in my birthplace, the small northern town from which my odd accent derives? As if that weren’t enough, I’m offered a novel set where my parents grew up, a similar down-at-heel out-of-the-way place where I had my first restaurant meal. Sixty miles separates these two towns, as well as some breath-taking countryside, as depicted in The Wolf Border, one of my favourite reads from last year. But Workington and Barrow don’t have the beauty of the Lake District. Thanks to Vintage Books and Legend Press, I had the chance to discover whether they could nevertheless shine on the page. I’d be interested in your thoughts on using real places as fictional settings.

I’m proud to be taking the reins this week at the Carrot Ranch, with a flash fiction prompt on showing someone around a property. My theme arose partly from the open weekend at North Lees Hall, which attracted over a thousand visitors across the two days. Although I got rather chilled standing in the doorway trying to steer a one-way system on the two sets of stairs, it was great fun. For those who couldn’t make it to Derbyshire, here’s a virtual tour of the house, both inside and out. Did you notice the p-word in my opening sentence? Did it make you wince? If so, I hope I can persuade you that, not only is the adjective perfectly apt for the purpose, you should lay claim to it yourself.

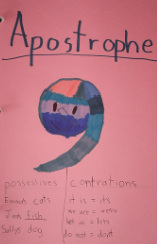

Dr Mary Charlton is “a fully qualified Jungian therapist, with a doctorate in neuropsychology and over twenty-five years’ experience in the NHS and private practice” (p39) who also claims to have worked as a clinical psychologist (p246), an unlikely combination to my mind but, knowing little about either Jung or neuropsychology, I’d better leave her to it. But she does highlight two areas not much addressed in this series on fictional therapists that merit a closer look. While previous fictional therapists, such as Gabrielle Fox, Max Fisher and Tom Seymour, have worked with children, Mary Charlton is the first I’ve encountered doing so outside a team setting. Twelve-year-old Ben Dixon finds his way to her on the recommendation of a friend, who is also a former client (I know, boundary violation alert). Although Mary knows that she can’t work with Ben without parental consent, her willingness to take him into her office and let him talk about his difficulties before this is forthcoming and, later, to spend time with him outside her consulting room when the boy’s father has expressly forbidden it puts her on ethical dodgy ground.  Stephen is in trouble, suspended from work after a violent outburst that’s left him shaken and his wife concerned for their shared future. She wants him to talk about his childhood; he is terrified of resurrecting the ghosts of the past. Yet when he gets a phone call telling him his mother is unwell, he decides it’s time to pay her a visit in the town where the events of a single day shattered so many lives. You know you’re in safe hands with a writer who uses the word crescendo¹ correctly on the first page, and comes with an endorsement from Alison Moore. That Dark Remembered Day bubbles with elegant descriptions from the Cornish coast to the windswept Falklands as the past is uncovered layer by layer until the full horror of that day’s events are finally revealed.  I do love the way fiction can take me to unexpected places, not just as a reader, but as a writer, too. A couple of weeks ago, I was surprised to find inspiration for a short story in Margaret Thatcher's funeral. Now I'm hanging out with mediaeval nuns. I'm greatly enjoying the company, but I feel a terrible fraud, seeing as I'm totally unqualified as a historian. I think I've got an O level in history, but that would've been on the industrial revolution and, even as someone who believes my computer works by magic, it's hard to imagine the lives of people in a pre-mechanistic age. Except, I remind myself, in some parts of the world life is still like that, and I have had the privilege of passing through some such communities and catching a glimpse of what it's like to live without running water or electricity. So maybe I've got more to draw on than I thought. Nevertheless, not having previously delved into history any further back than my parents' childhoods, it is quite a different experience for me having to constantly check my facts (and, if it weren't for the internet, it would be far too arduous a task for one short story). For example, I knew not to have my nuns growing potatoes (although spuds were on my mind having just, belatedly, planted mine in the garden), but what other vegetables that we now take for granted would not be available in the Middle Ages? Fact checking was fairly straightforward, however, but what about the language? My dictionary does give a rough date for when various words were introduced, but how authentic did I have to be? How authentic was I capable of being, without immersing myself in contemporaneous documents for a couple of months? Where I stumbled most was with verbs as metaphor, or muscular verbs. I balked at using the word drive to indicate motivation or compulsion, because of its automatic association with motor transport for modern readers, even though I'm sure the word would have served equally well in the Middle Ages for driving cattle. I don't think this issue is unique to historical fiction, more an extreme case of something we need to think about in all our writing. Have we got the facts right, or near enough that they won't derail the story, and is the language consistent with the character and setting? Or perhaps I'm just trying to cover myself for straying into territory where I have no right to be? Interesting also how the blog leads me to the unexpected, not just the fun stuff I find on other people's, but what I choose to post. In other words, I hadn't expected to do this one, but the other two I mentioned last time (on identity as a writer and on blogging) need a little more polishing and there's bank holiday sunshine promised here in England, so I'll give them a bit more time to ripen. Meanwhile, whether or not you have delved into historical fiction, as a reader or a writer, please share your views.  Of course not, but Mid Devon district council has apparently decided to remove them from their street signs because some people are confused about how to use them. Lucy Mangan regards this response as symptomatic of a political short termism that refuses to address the underlying causes. I also wonder if the attack on correct grammar – as if it’s somehow elitist (and elitist meaning bad when it’s about knowledge but not when it’s about “earning” as much in an hour as others do in a year) to know your its from your it’s – partly stems from the repressed grief of little boys who started school too young. At some level, reading and writing is always going to be hateful if it’s forced upon you at four or five before you are ready rather than at six or seven as, for example, in Hungary and Spain. Because this is no mere plea for flexibility, it is an attack. Even as we roll our eyes, we tolerate – don’t we? – the misspelt signs outside the greengrocer’s and celebrate the fact that we still have a greengrocer’s and the proprietor can calculate the bill in their head. But public institutions are different. They need to follow the rules. The rules of grammar are there to make things easier for everyone. Yes even for those who don’t know how to work them. At the beginning of each new term, I stand up with the rest of the choir and listen intently as the pianist plays the introductory bars of the music. I watch the conductor but I don’t dare open my mouth when he gives us the signal to sing. I follow the dots on the page as best I can as the rest of them go through the first trial run. I know the very basics of the grammar of music, but not nearly enough to join in until I’ve got at least the ghost of the tune in my head. Sometimes, looking at a mass of squiggles I thought I’d mastered the week before, I think it would be easier if none of us could read music, then we’d all be the same boat. I wouldn’t feel so stupid. But then there wouldn’t be anyone to explain what that little cap over that note means, and we wouldn’t be able to sing such complex music, or so much of it, because we’d have to learn it all by heart. I wonder if those who are frustrated by grammar could be supported to recognise its value the way I appreciate my musical scores. I’ve still a bit more practice to put in before the concert, but I’ll be taking my place along with the other sopranos, tuned into the music with everything I’ve got. These are my favourite parts of the programme: You can listen and follow the music to Locus iste (of course we sing it better). Or dance along to John Rutter’s Gloria. Got to dash: I'm off to a rehearsal.  The work and pensions secretary, Iain Duncan Smith, claims he can live like common people on benefits of £53 a week, 15% of median earnings, apparently. Well, obviously that's a red rag to a journalist who will find very good copy in showing it just can't be done (Lucy Mangan) and would prove nothing if it could (Zoe Williams: what's one week of discomfort in the midst of fifty-two in relative luxury?). Might also have been a red rag to this blogger, given that I live in the computer, walk everywhere and my favourite food is lentils. I thought I might manage it if I pretended I wanted to do the 5:2 diet and the last two days were fast days, until I remembered that I wouldn't be able to use the computer I bought back in January because, at a cost of 13 weeks' benefits, I couldn't have afforded it. More disturbing, however, than these glib comments that suggest our politicians have a limited understanding of living on the breadline, is the continual drip feed of misinformation about the poor that comes from official channels. The DWP could soon start running masterclasses in point of view and the unreliable narrator. Perhaps that would be a healthier way of managing the debt than demonising a group of people who are already down: Fraud, which accounts for less than 1% of the overall benefits bill, was

Until last week, I hadn’t written any fiction for over two months. I’d entertained passing thoughts about revisions I should make to my novel and a few fleeting ideas for short stories, but nothing sufficiently inspiring for me to do any actual writing. I don’t believe in writer’s block (that’s for another post), although I hadn’t planned on so long a break. Besides, I was sending out stories (see next post) and writing the blog, buzzing with ideas and words, and fascinated by how absorbing I found it (another post on that coming soon, too), but it wasn’t fiction – or not quite. Anyway, last week a story finally got written and I realised two things I get from fiction that I don’t get other kinds of creative writing. The first is how the characters lend a hand in the crafting of the story (but I think I’ve got enough to say about that for another post) and the second is the sheer alleluia joy of language.  I try to write well even if it’s just a note to the milkman (and no, this isn’t poetic licence, we still have our milk delivered even if it is twice the price, and I’ll occasionally write notes to the man who brings it) and I draft and check my blog posts (you think this is bad you should see the originals) but it’s in fiction where I want the language to fly. I’m no poet by any means, but when I changed Dad held his mug to Dad cradled his mug in my new story, even if I might have changed it back again, I knew I’d come home. Muscular verbs bring vigour to our writing without recourse to those pesky adverbs. They're appealingly economical, enhancing the description without upping the word count. Choosing the right one can be a load of fun. But we need to be careful not to get carried away. Too much muscle and it gets exhausting. Sometimes I really need to just walk into a room and curb my desire to amble, bounce, careen, dance, edge, flounce, gambol, hobble, etc. Actually, when it gets to that stage there’s probably no need to show the transition into the room at all. Since I’m back into writing stories, next up is a post on how to publish them. In the meantime … How about you? Do you get turned on by muscular verbs? Which are your favourites and are there any you overuse? Or is there something else about fiction writing that other forms of writing don’t quite touch? |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed