Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

My final two reviews of 2022 are tenuously linked by being set in closed communities in which unempathic people hold vulnerable creatures in their power. I refer to creatures less because the staff of the nightmare care home in the first novel don’t seem to regard their charges as human and more because the inmates of the second – where the compassion of the lowliest employee almost compensates for the attitude of her senior colleagues – are dolphins.

8 Comments

I’m sharing my reflections on these recent reads about the aftermath of a family tragedy, the first set in 1970s rural England and the second in contemporary Alabama. Both are by women writers whose previous novels I’ve loved and I’m delighted to say they didn’t disappoint.

Two debut novels from female British writers featuring dodgy scientific experiments on nonconsenting participants within very dark periods of history: the holocaust in the first and the transatlantic slave trade in the second. Yet, despite both also featuring women disempowered by their husbands, and voluntary and involuntary drug abuse, each contains a thread of hope in a love story.

Two novels with a fantasy element: the first set in the near future; the second a century in the past. Both feature humans with transmuted bodies: the first through an accelerated process of devolution; the second as a congenital condition, although the explorers who come upon them believe they represent an intermediate stage in human evolution.

Excuse me for bridging such different novels, although both are about the challenge of connection, one looking to the future and the other to the past. In the first, translated from the French, a famous artist juggles the contradictions of Christian and Muslim cultures when he’s commissioned to design a bridge between two shores of a capital city. In the second, a teenage boy more comfortable in the virtual world than the human, ends up fighting for his life when he forges stronger connections between the hemispheres of his brain.

I’m linking these novels less for the arboreal coincidence of the titles but because each is about the impact of another culture’s approach to death and/or ageing on a Westerner’s life. For the first, six months as a young man deep in the forest of a remote Micronesian island determine the course of his professional and domestic life; for the second, a glimpse of the culture of the Toraja people in Indonesia in middle age helps him mourn the loss of a close friend.

No prizes for guessing why I’ve connected these two novels; I don’t think I’ve ever read another book with gravity in the title – although The Weightless World is about a antigravity machine – and then I find two published in the same month. But rest assured, they’re very different reads: in the first, Lotte feels a stronger pull towards the stars in the sky than her earthly attachments; in the second, love is a force that can furnish reconnections across continents and years.

I like fiction that shows the characters at work, but it can be difficult to pull off convincingly. While approaching it from very different angles – British writer Lucy Atkins in a thriller about a highflying TV presenter and historian; American Helen Phillips in a satire about a data entry clerk – both have produced extremely satisfying reads.

A historical novel about Arctic exploration or a novel set in a near-future South Africa? A romance or an account of a relationship falling apart? A motherless girl or a fatherless boy? Wild animals or ice? Both of these novels explore the conflict and compassion that connects us to the natural world, but it was a bonus for me to read that the protagonist of Green Lion told his friend that his father was killed in a hunting accident in the Arctic, the setting of Under a Pole Star. Read on to see if I was right to pair these reviews.

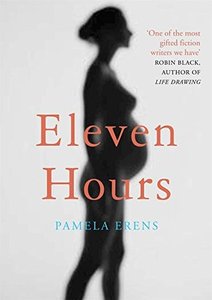

In between celebrating my book’s first birthday – and finding the clichéd book-as-baby metaphor more apt than ever – I’ve had the pleasure of reading three novels about the begetting of real human babies: a debut scientific thriller from England; a second gritty comedy from Scotland; a third novel in the literary genre from the USA. As if the authors have responded to a writing prompt to bring a novel angle to “having” a baby, there should be something for everyone in this selection. If you’d like to recommend any others, you can do so via the comments.

Paul and Veblen are engaged to be married. They’re clearly in love and clearly, with their mismatched attitudes to the world beyond themselves, unsuited for the decades of companionship we hope will follow a wedding. It is obvious from the moment Paul gives her a ring, with a diamond so large it interferes with her obsessional typing. Unlike Veblen, who espouses the anti-capitalist values of her namesake, the economist Thorstein Veblen, Paul is ambitious. A research neurologist, when the pharmaceutical empire Hutmacher offers him the opportunity to begin clinical trials on the device he’s developed to minimise battlefield brain damage, he dismisses his ethical reservations with the word Seropurulent “an ironic superlative they used in med school for terrible things that had to be overlooked” (p62). Raised by hippies, the trappings of the consumerist world spell safety for Paul (p66):  With three high-profile husbands and two serious relationships with female colleagues, the life of the anthropologist, Margaret Mead, seems to have been as original as her research endeavours. While criticised as both a woman in a man’s world and a populariser of social science, as well as her findings on the sexual freedoms of Samoan society being subject to challenge, she remains – according to my totally unscientific survey of one – the best-known anthropologist of all time. In Euphoria, Lily King brings her vividly to life in this fictionalised account of a woman with a very similar history to Mead’s during a period of fieldwork along New Guinea’s Sepik river in 1933. Nell and her husband Fen – malarial, injured and dejected after five months with the dreadful Mumbanyo tribe, she in particular despairing at their neglect and mistreatment of babies – are about to return to Australia when Bankson, another anthropologist based on Mead’s third husband, Gregory Bateson, familiar to me through the double-blind theory, persuades them to reconsider.  I do love the way fiction can take me to unexpected places, not just as a reader, but as a writer, too. A couple of weeks ago, I was surprised to find inspiration for a short story in Margaret Thatcher's funeral. Now I'm hanging out with mediaeval nuns. I'm greatly enjoying the company, but I feel a terrible fraud, seeing as I'm totally unqualified as a historian. I think I've got an O level in history, but that would've been on the industrial revolution and, even as someone who believes my computer works by magic, it's hard to imagine the lives of people in a pre-mechanistic age. Except, I remind myself, in some parts of the world life is still like that, and I have had the privilege of passing through some such communities and catching a glimpse of what it's like to live without running water or electricity. So maybe I've got more to draw on than I thought. Nevertheless, not having previously delved into history any further back than my parents' childhoods, it is quite a different experience for me having to constantly check my facts (and, if it weren't for the internet, it would be far too arduous a task for one short story). For example, I knew not to have my nuns growing potatoes (although spuds were on my mind having just, belatedly, planted mine in the garden), but what other vegetables that we now take for granted would not be available in the Middle Ages? Fact checking was fairly straightforward, however, but what about the language? My dictionary does give a rough date for when various words were introduced, but how authentic did I have to be? How authentic was I capable of being, without immersing myself in contemporaneous documents for a couple of months? Where I stumbled most was with verbs as metaphor, or muscular verbs. I balked at using the word drive to indicate motivation or compulsion, because of its automatic association with motor transport for modern readers, even though I'm sure the word would have served equally well in the Middle Ages for driving cattle. I don't think this issue is unique to historical fiction, more an extreme case of something we need to think about in all our writing. Have we got the facts right, or near enough that they won't derail the story, and is the language consistent with the character and setting? Or perhaps I'm just trying to cover myself for straying into territory where I have no right to be? Interesting also how the blog leads me to the unexpected, not just the fun stuff I find on other people's, but what I choose to post. In other words, I hadn't expected to do this one, but the other two I mentioned last time (on identity as a writer and on blogging) need a little more polishing and there's bank holiday sunshine promised here in England, so I'll give them a bit more time to ripen. Meanwhile, whether or not you have delved into historical fiction, as a reader or a writer, please share your views.  A lot of my fiction is transformative: I'll take a disturbing event from my own life or what I see around me and, by re-authoring it, make it more manageable. It tends to be a retrospective process, the idea for the story coming long after the event has taken place. But something different has being happening with a short story I've been working on last week. I'd never have imagined I'd have written a story with a backdrop of Margaret Thatcher's funeral. I'd never have imagined I'd be following the events on the telly. Yet shortly after her death was announced, the seed of the story had been planted inside me. Then, in place of the rage that the government could fritter away £10 million of taxpayers' money for a not-quite state funeral when they are so mean about disability benefits, I'm calm and curious. Sometimes it's hard being a writer but it makes sense for surviving these topsy-turvy times. But that was the state of play as far as Thursday. You know that thing about too much research? Never my problem, generally, as I take a lazy/pragmatic attitude and do as little as I can get away with. I had enough for my story with what the funeral might mean to people who feel their lives been blighted by her political career. Yet even as an extremely passive researcher, I couldn't shut out the other things that were happening, other reactions and protests. So now I'm left wondering whether somehow I've got to fit that Ding Dong The Witch Is Dead song into my story. I won't really know until next week when all the pomp and protest has died down if my story has been killed or not. Don't you ever wish real life would just shut up and go away? My next post will probably be on author bios and the published novelist's itinerant lifestyle. Do come back -- I promise you the writing will be sharper than these photos.

|

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed