Nell and her husband Fen – malarial, injured and dejected after five months with the dreadful Mumbanyo tribe, she in particular despairing at their neglect and mistreatment of babies – are about to return to Australia when Bankson, another anthropologist based on Mead’s third husband, Gregory Bateson, familiar to me through the double-blind theory, persuades them to reconsider.

The author of a highly successful book on her earlier fieldwork, Nell is a more natural anthropologist, in contrast to her somewhat resentful husband (p106-7):

Fen didn’t want to study the natives; he wanted to be a native. His attraction to anthropology was not to puzzle out the story of humanity. It was not ontological. It was to live without shoes and eat from his hands and fart in public … His interests lay in experiencing, in doing. Thinking was derivative. Dull. The opposite of living. Whereas she suffered through the humidity and the sago and the lack of plumbing only for the thinking. As a little girl … she wished for a band of gypsies to climb up into her window and take her away with them to teach her their language and their customs. She imagined how … she would tell her family all about these people. Her stories would go on for days. The pleasurable part of the fantasy was always in the coming home and relating what she had seen. Always in her mind there had been the belief that somewhere on earth there was a better way to live, and that she would find it.

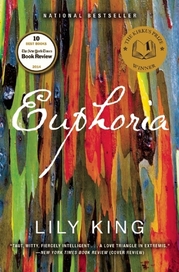

Bankson is beguiled by her, not only learning from her observational methods but falling in love with her as a woman, neither of which go unnoticed by her husband. While the threesome do share a sense of euphoria in a night of genuine intellectual creativity, the combination of ego, drive and conflicting values lead to tragedy, not just for them but for the Tam people who had welcomed them into their community.

It can take a substantial amount of research to write convincingly about research, but Lily King handles hers particularly well, demonstrating the rigorous discipline and intense delight in the discovery of something new, along with the reservations and doubts. The participant-observer method, with the fine balance of objectivity and subjectivity brings particular risks of misinterpretation (p177):

I couldn’t help questioning the research. When only one person is the expert on the particular people, do we learn more about the people or the anthropologist when we read the analysis? As usual, I found myself more interested in that intersection than anything else.

I know from personal experience on a much smaller scale (through my own research employing the psychodynamic observation methodology derived from anthropology) how exciting the discoveries made at the intersection between inside and outside can be. It’s an excitement that can veer into mania (p177-8):

Looking at our faces you might have said we were all feverish and half mad … made us feel we could rip the stars from the sky and write the world anew … reminded me of the finale of a fireworks show, many flares sent up at once, exploding one after the other. She claimed that because of the emphasis in the West on private property, our freedom was restricted much more than in many primitive societies. She said that it was often taboo in a culture to have a real discussion of the dominant traits; in our culture, for example, a real discussion of capitalism or war was not permitted, suggesting that these dominant traits have become compulsive and overgrown

yet with a jubilant audacity in turning the observing gaze onto one’s own community.

It’s perhaps similarly grandiose for me to link to my research (actually, I was surprised the search engine found it so quickly, even if it is just the abstract), but it’s almost a reminder to myself of the connection I made to this book. (As an aside, I’m smiling at some feedback from someone who read my blog title as Ann-ethology.) A better comparison, and one more familiar to my blog readers, might be to the hours of painstaking attention to the other that must have gone into Stephen Grosz’s The Examined Life. Perhaps these are matters better pursued in the comments and discussion, should anyone be interested. So I’ll sign off now with thanks to Picador for my review copy of this wonderfully engaging novel.

| This being the end of another month, I’m leaving you with a reminder of my September reviews. Click on the image to go to any you might have missed. And, as it’s also World Translation Day, it’s also worth noting that one third of these are translations. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed