Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

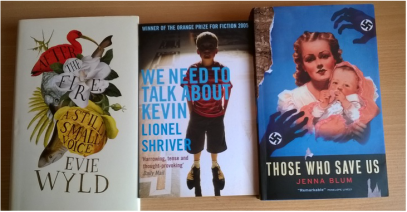

In a recent post, I explored how the experience of terror and trauma can have lasting repercussions for the individual concerned. I’m also interested, both as a reader and writer, in how the impact can reverberate across the generations. Would a parent’s exposure to unspeakable horrors make them overprotective towards their own children? Would the struggle for survival render them so emotionally blunted they’re unable to give the children the love they need? Would their pleasure in the easier life they’ve created for their children be marred by envy?

17 Comments

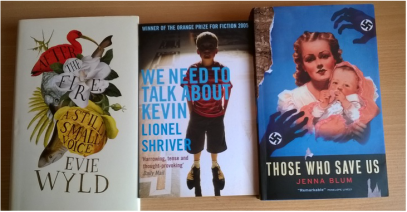

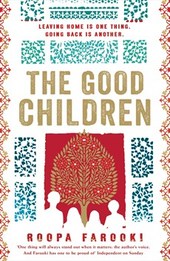

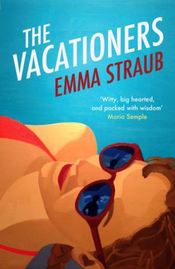

For most of my 20s I lived with a man who had spent his early years in a village in Punjab. His father, despite being permanently settled in the UK and not having a huge amount of surplus cash, was determined to buy a house with a plot of land for each of his sons “back home”. In his mind, it was worth going without in his current place of residence to invest in the place where his family had lived for generations. I was reminded of this on reading Johanna Lane’s debut novel, Black Lake. An Indian immigrant might seem worlds away from of a country gentleman in Donegal, yet my ex-boyfriend’s father and Irish patriarch, John Campbell, shared a similar tenacious attachment to their ancestral lands. While one moved thousands of miles away and the other made an uncomfortable compromise to enable him to stay, both their identities were rooted in the soil of their homelands.  What do you understand by the term “a good child”? Does it imply a particular proficiency in getting up to mischief and other childish things? Or does it mean, as for the Saddeq children growing up in Lahore in the new nation of Pakistan, suppressing their own inclinations and desires in favour of their mother’s strict demands? In a divide-a-rule regime reminiscent of the British Raj, the boys, Sully and Jakie, are destined to be doctors, their learning beaten into them by a tutor they nickname, appropriately, Basher, while the girls, Mae and little Lana, hug their mother’s shadow, dressed up like dolls in scratchy frilly dresses unsuitable for the suffocating heat. Until the day they can escape their manipulative mother through marriage for the girls and education abroad for the boys, they have no choice but to comply. How well-prepared are such good children for their future adult lives? As the novel explores, children who are discouraged from questioning authority might struggle to protect themselves by appropriately saying no. On the surface, the Saddeq offspring are successful: they have careers, relationships, children of their own. But, in different ways, they are still, even in late middle age, the insecure children their mother created, maintaining as wide a distance as they dare from their parents, still scared of their mother when duty calls them “home”. Compulsive helpers, workaholics, conflicted about intimacy; even into old age they continue striving to be good rather than happy.  Oh, Professor Lodge, if only you’d named this novel A Narcissist’s Diary or perhaps Tubby’s Dodgy Knee. But Therapy! The title’s crying out for a place in this series, and you know what that means. Yes, I had to read the thing, and think about it, and I so hate doing negative reviews (and I am doing so only in the knowledge that you are big enough to take it/be totally unaware that I live and breathe on this earth). Yes, I could’ve bailed out when I realised your title encompasses a broad church of therapy: physiotherapy; aromatherapy; acupuncture and a rambling form of cognitive-behaviour therapy for which the dreadful manualised Improving Access to Psychological Therapies might have been especially invented – but I’d already paid for the book. I hardly cared that your narrator’s bungled attempt to clarify the difference between a psychiatrist and a cognitive-behaviour therapist (p15) had me longing to introduce you to Sally Vickers, whose novel, The Other Side of You, featured my last therapist but one. In fact it was almost a relief to be jolted out of my stupor by the subsequent revelation (p212) that said cognitive-behavioural therapist was licensed to prescribe antidepressant medication, outing her as a psychiatrist (or some other kind of medical doctor) after all. Yet I’d have gladly renounced my pedantry in exchange for a spark of connection with character or story to lift me above the morass of ennui.  When Nina first encounters Emma in the street after all these years, she seems afraid and at pains to avoid her. But by the end of the summer she’s engineered an entry into the other woman’s life via a piece of mischief disguised as a favour. Over the next few months, Nina makes herself Emma’s confidante, while secretly despising her both for the narrowness of her current existence and for some as yet undisclosed transgression in the past. Emma, exhausted by early motherhood and adrift from her previous professional persona, is flattered by Nina’s attention and unconscious of any previous encounter. In chapters of exquisite prose narrated by alternate women, we glimpse their separate and intersecting lives to eventually discover the root of Nina’s grudge against Emma and how far she will go to wreak her revenge.  Thanks to everyone who contributed to the lively discussion sparked by my recent blog post on the “stolen head” novel. While this focused mainly on voice and point of view, we also had some fun on Twitter with the gruesome label. This prospective disembodied head reminded me of a radio play I caught many years ago about a brain that was enabled to carry on living after the body that had hosted it had died. A wonderful piece of slipstream fiction, it raised all kinds of questions about our relationships with our bodies, especially for those of us who value a life of the mind. How much and what kind of attention do we pay to our bodies? Do they go unnoticed until, as Clare O’Dea explores, their defences are breached through illness or injury? Do we begin to appreciate their mechanics only when it comes to describing the physicality of a character possessed of a different shaped body to our own? Do we treat them as a project to be altered, improved and perfected, rather like we’d remodel our homes?  A flawed family and a selection of their mismatched friends unpack their baggage in an isolated holiday villa: what could possibly go right? Franny puts her energy into shopping and cooking for the tribe, anything to take her mind off what has led to husband, Jim, losing his job. Their late-twenties-going-on-twelve son, Bobby, has brought along his own work and relationship problems in the form of unsuitable girlfriend, Carmen, while eighteen-year-old Sylvia is desperate to reinvent herself before setting off for college. Then there are the lovebirds, Charles and Lawrence: can their marriage survive the challenge of waiting to adopt a baby in the midst of Franny’s attempts to monopolise her oldest friend? And if that isn’t enough to light the blue touchpaper, Sylvia’s handsome Spanish tutor brings that extra spark.  Thank you, Norah Colvin, for another blogging award. Versatile isn’t a word I’d readily use to describe myself but, if Norah thinks this blog qualifies, I’ll happily accept. The Versatile Blogger Award asks recipients to thank their sponsor (done that), nominate another fifteen blogs (that might take some time, but I’ve started the ball rolling below) and tell everyone seven things about yourself. I’m sure I read somewhere it’s supposed to be seven interesting things; fortunately, Norah hasn’t set the barrier as high as that. I thought I’d take it as an invitation to illustrate the extent and limitations of my versatility, and have a bit of fun along the way. Some of these even come in multiples of seven. |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed