He wonders if it's an indication of their triumph or failure as parents that Pollyanna thinks prison would bring a spark of excitement into her life. That they've shielded her so completely from their own nightmares that she hardly knows who her mother is.

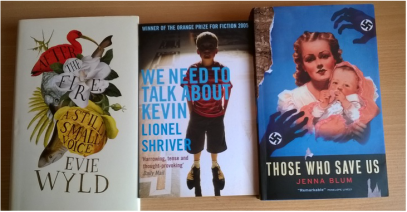

and it’s also one of the themes of Jenna Blum’s debut novel, Those Who Save Us. Anna Schlemmer has never been a popular member of the rural Minnesota community to which she came to live, with her three-year-old daughter, Trudy, after the end of the Second World War. Now a middle-aged historian, Trudy has always been frustrated at her mother’s refusal to talk about her previous life in Nazi Germany. Yet Anna’s emotional distance from both her daughter and her neighbours becomes more understandable as we discover the lengths to which she had to go to ensure their survival. (Note: Jenna Blum was so dedicated to getting under Anna’s skin that she dressed as her character would have done while writing this novel.)

Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk about Kevin is concerned with a mother-child relationship that is even more fraught. The debate among readers about the extent to which Eva can be considered culpable in raising a child who commits such a horrific crime has a tendency to mask the equally interesting question of the impact of transgenerational trauma on the character of Eva herself. Kevin rejects his half Armenian background, yet the high-school killings mirror another massacre, the 1915 Armenian genocide that history has largely overlooked. In the novel, Eva’s mother becomes agoraphobic and withdrawn; Eva, an ardent traveller, is equally fearful of being trapped at home. Both these women, apparent polar opposites, can be said to be living the legacy of a collective trauma. This theme is eloquently explored in a conversation between Lionel Shriver the psychotherapist Angela Joyce.

Evie Wyld’s debut novel, After the Fire, a Still Small Voice, is about the impact of war on men across three generations. As a teenager, Leon holds together the family business when his father volunteers to fight in the Korean War. On his return, his father is unable to resume his prewar role and, when Leon himself is called up to fight in Vietnam, he puts a note on the shop door: Closed for the Time Being. A generation later, his own son, Frank, leaves a violent relationship, and moves to a shack previously owned by his grandparents on the Queensland coast. He wants to make new start, to shrug off the legacy of conflict with his father, but he lacks the internal resources to create a different kind of life.

The latest prompt from Charli Mills over on the Carrot Ranch is to write a story in exactly 99 words that considers history, near or far. My contribution hinges on aspects of family history that can’t easily be spoken about:

My sister dived into the shrubbery. “She’ll never look for us here.”

I bit my lip. “But it’s cheating.”

Across the park, Mum was calling: “Coming, ready or not!”

She wasn’t like the other mothers, too busy to chat or play. Mum bubbled with stories of her carefree childhood at the big house, of games of Hide and Seek with handsome stable boys.

“Come on!” My sister grabbed my hand from between the leaves, a purple flower crowning her head like a giant bow. Sick rose to my throat. Mum hated rhododendrons the way I hated geometry and spinach.

Regular readers might recognise this as another angle on (prequel to?) an earlier flash, and I’m not sure how well the story works without this context. If you’re interested, you’ll also find a photo of my garden rhododendrons in that post!

I welcome your feedback. Do you think the trauma of one generation can be passed on to the next? If you’ve read any of these novels, what’s your view on the importance of this theme?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed