| Charli tells us this week she feels like a fish out of water in Nevada. If she – a Californian – feels estranged, what would it be like for this Brit? As it happens, I’ve been to Nevada. I had a major life event there. But, as I’m sure Charli would tell you, Las Vegas doesn’t represent the whole state. |

Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

6 Comments

I’m busy working towards the publication of my next novel, Lyrics for the Loved Ones, the sequel to Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home, in May 2023. It’s set mostly in a care home leading up to, and in the early weeks of, the pandemic. So I’m happy to showcase a couple of other novels on the theme, with the bonus that they feature places I’ve been. The first is set during the second UK lockdown in November 2020; the second in North and South America when the world closed down in March that year.

Two translated novels – the first from Hebrew, the second from French – about young people invited to apply for grants to support their ambitions, which lead them into damaging situations. The first is about a tour guide to the Nazi death camps; the second about a teenage dancer groomed for abuse (with a section from the point of view of her school boyfriend, who feels burdened by his Jewish heritage). They question whether the legacy of such cruelty is to forgive, forget or become monsters ourselves. Difficult subjects, but both an easy and worthwhile read.

I’m sharing my reflections on two novels, published a few years ago about retired schoolteachers who are forced to reappraise aspects of their pasts. Julia Garnet, a former history teacher in South London, has her epiphany in Venice; former maths teacher, Olive Kitteridge, stays in her home town in Maine. Both women have hidden their vulnerabilities beneath a steely shell. Both demonstrate it’s never too late to learn.

These two novels defy easy categorisation, but I’ve paired them for the combination of depth and humour, innovative structure and switching points of view. Both feature the dynamics of family and coupledom, and a holiday – the first in Scotland, the second in Italy – with destructive consequences.

Strange bedfellows these two translations: the first an historical novel from France; the second a contemporary slipstream novel from South Korea. My excuse for linking them is an issue that was on my mind the day I finished the first and started the second, thanks to a non-fiction book I had ordered. Although women being blamed for sexual abuse and harassment is only a minor issue in these novels, it’s so important I make no apology for ushering it into the limelight.

In both these novels, the first set in contemporary New York and Nice and the second in a hypothetical future Tokyo, an older man is looking after a young relative in less than ideal circumstances. In different ways, they illustrate generational interdependence and how the past actions, or inactions, of the older generation have brought about some of the difficulties experienced by the young.

My first post of the month features a couple of debut novels in which young women seek to reconnect with a man who had a major influence on their childhood. Both men are – intentionally or accidentally – involved in local politics, but the personal is equally vital to the women. In the first, set in India, it’s a friendship forged by her mother in defiance of class and convention; in the second, set in Nigeria, it’s the courage and compassion to advocate for the underdog. The orange hue on the covers is pure coincidence; likewise that both authors’ surnames begin with V!

Here are two novels in which the narrator looks back on past connections: the first a coming-of-age tale during Ireland’s electrification; the second a writer’s stream-of-consciousness(ish) look at her Tunisian roots. The colour-coordinated covers is pure coincidence. This week’s 99-word story in response to the prompt ‘the greatest gift’ follows my reviews.

I wouldn’t have expected to read one short novel/novella featuring time travel, let alone two, both translations, published within a week of each other in the UK. But here they are: the first, a light comedy from a French author, in which time travel is central to the plot; the second, a dark but not bleak reflection on childhood, in which a metaphorical time travel brings redemption.

Two novels in which a marriage of a twenty-something man and woman from superficially similar backgrounds shows early signs of strain. In the first, between Muslims in contemporary London, the politics of religion are problematic right from the start; in the second, life gets tough when a new mother follows her journalist husband to a posting in newly-independent Ukraine. All harbour secrets, communication suffers and trust is hard to find. But, with youth on their side, they’ll take something from the experience, whether or not the marriages survive.

While very different in style and focus, both these recently-published novels send women on road trips to learn about their individual identities within the context of contemporary Britain. In the first, three Scottish Muslim women with origins in the Arab world leave the city for a lochside holiday where they meet a talking hoopoe. In the second, a Londoner travels with her partner across Europe in a campervan encountering figures from the political and artistic past.

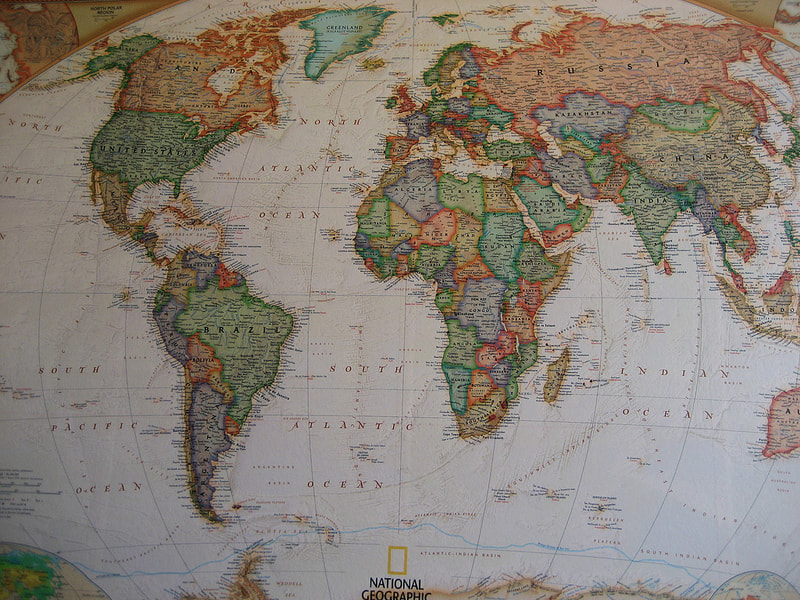

Three short reviews of quirky novels published in the UK this month that have taken me around the world without having to leave my armchair. The first, set in Australia, marries historical fact with a lonely alien visitor. The second, set in South Africa, posits an alternative near future where the sick are quarantined. The third, a German translation set in Japan, pairs a suicidal student with an expert on beards for a journey in the footsteps of a revered haiku poet.

Two novels which feature murders, and the police called in to investigate, but with much more about them than that. The first is a German satire on the European Union; the second a love story set in Belize.

My first reviews of books published in the UK in 2019 are another two translations: the first from French and the second from Dutch. Both feature young people getting dangerously out of their depth, although, at 12 ¾, the boys in the first are probably around half the age of the young women in the second. See if either takes your fancy.

As if my head weren’t buzzing enough with the enigma of identity, I’ve recently read two translated novels exploring the gap between where the characters come from and where they ended up. In the first, a forty-something German man has given little thought to his origins across the border; in the second, two women, juggle loneliness and language difficulties as they gradually acclimatise to new lives in Australia, far from home.

Fictional writers can be tricky on the page; sometimes I suspect a character’s assigned the job because the author’s unfamiliar with more run-of-the-mill kinds of work. But, like anything else that’s slightly iffy, if you’re going to go for it, it’s best to go for it big time. That’s what Irish writer John Boyne does with his larger-than-life antihero Maurice Swift and American Andrew Sean Greer with “failed novelist” Arthur Less, both simultaneously managing to address the wider issues of human vanity and what constitutes a well-lived life.

If you’re going on holiday this summer, you might be tempted to take one of these novels with you. The first focuses on the people who entertain and assist the visitors to a Victorian pier at an English seaside resort across a period of over a century; the second on a family taking a long holiday together on the coast of Finland. But, of course, while it might be all smiles and bonhomie on the surface, there are disconcerting undercurrents to keep you turning the page. Let me know which takes your fancy.

When we find ourselves unmoored, we might be extra motivated to seek to consolidate our roots. That’s the slim connection between these two novels in which a woman confronting terrible loss decides to research her family tree. Both involve a story of migration: Jane Ashland’s ancestors moved from Norway to the USA; Neha’s in The One Who Wrote Destiny came from Kenya (and before that India) to the UK. For another novel about tracing the members of an extended family, see Kintu.

Two novels in which men consider suicide; doesn’t sound very jolly, does it? But there’s rather more to both these stories, as well as the coincidence of texts punctuated by philosophical aphorisms. Read on and see what you think! And before you leave, check out my latest 99-word story linking suicide, unlikely weather and ravens.

I’m sharing my reflections on two novels in which sensitive men share their reflections on life and love. Both begin with the narrators at a loose end during the university summer vacation, the first in Barcelona, the second in London. Wabi-Sabi is the lighter of the two, in which a university lecturer travels to Japan where he is beguiled by a young woman. In The Only Story, a man’s entire life is shaped by a ten-year relationship with a vulnerable older woman he began as a nineteen-year-old student.

|

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed