| While I’m neither a reader nor a writer of poetry, I do appreciate that the shape of the lines on the page matters, the white space almost as important as the words. But does something similar apply to fiction? Do we need wide margins and paragraph breaks to give the sentences space to breathe? |

Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

10 Comments

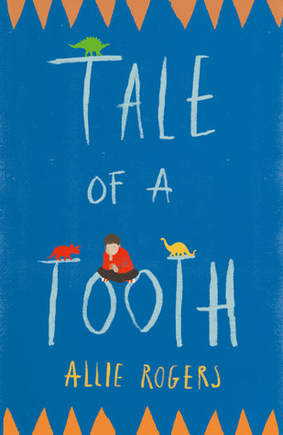

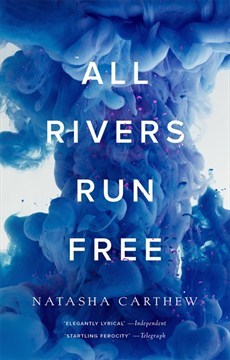

Martha might be twice the age of Ia in All Rivers Run Free, and could well have more than twice her education and wealth, but she shares her grief at lost loved-ones, and expectations, in a simple dwelling where the land meets the sea. Both are in parts of the British Isles that have suffered financial and cultural erosion as a result of English domination, although the Ireland where Martha’s deceased husband had a cottage is experiencing an economic revival, while Ia’s Cornwall is even more desolate for the rural poor than it is today. The authors of both these novels are female poets; read on to see whether either takes your fancy.

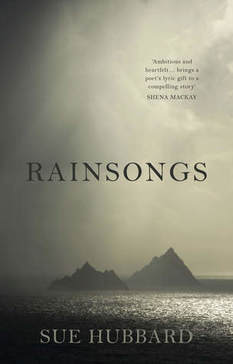

Two debut novels by women about women reviewing their (successful and stable) marriages in the context of an important relationship for one partner that’s not shared with the other. In the first, the wife’s passion for God and poetry leads her into the mind, arms and eventual bed of a man who isn’t her husband; in the second, the wife, emerging from her grief at her husband’s sudden death, becomes suspicious about the nature of his secret friendship with a woman he’s met on business trips abroad. Both authors employ non-linear structure to good effect.

When we find ourselves unmoored, we might be extra motivated to seek to consolidate our roots. That’s the slim connection between these two novels in which a woman confronting terrible loss decides to research her family tree. Both involve a story of migration: Jane Ashland’s ancestors moved from Norway to the USA; Neha’s in The One Who Wrote Destiny came from Kenya (and before that India) to the UK. For another novel about tracing the members of an extended family, see Kintu.

Would you rather lose the use of your body or lose your mind? Both so dreadful to contemplate; perhaps it’s just as well we don’t get to choose. And neither need we choose in fiction: both these novels about brain degeneration are worth your time. In the first, a concert pianist’s encroaching paralysis due to motor neurone disease is mirrored by the psychological immobility of his ex-wife. In the second, the reader can gradually make sense of the obsessions of a woman with senile dementia through the memories of her family and carers. Painful topics but, for those who need it, these novels provide a note of lightness too.

|

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed