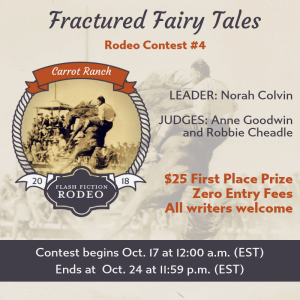

| It’s rutting season out on the moors again. The first time I heard a bolving deer (no, that’s not a mistype), I thought it was a motorbike. On Sunday, it made me think of the troll who hides under the bridge to scare the billy goats gruff. Or maybe not, if it’s the poor misunderstood creature in Norah Colvin’s fractured fairy tale. Now she’s inviting you to write one too. But beware, you have only 99-words to play with and I’ll be helping Norah, along with children’s author Robbie Cheadle, to select the best. |

Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

6 Comments

Our species has enslaved our fellow human beings for millennia, an abomination that continues to this day. While literature quite rightly reminds us of the industrial-scale trade in people between Africa, the Americas, Europe and the Caribbean, some historical human rights abuses are less well known. So, painful as the subject matter might be, I was pleased to widen my knowledge through these two novels: the first focusing on African slavery of other Africans in 19th-century Ghana; the second about people forcibly transported from 17th-century Iceland to Algeria. Both feature strong women from a period when female voices were often silenced and consider the psychological and political complexities beyond the polarised roles of victim and villain.

Both these novels are about Nigerian women and their relationships with their culture, politics, their children and their men.

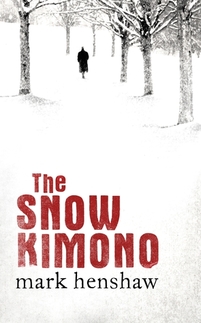

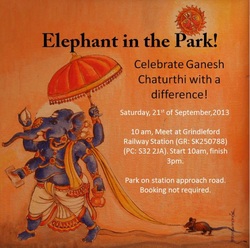

Writers of fiction and creative non-fiction know the value of metaphor. So you might be interested in recent research by Adam Fetterman and colleagues suggesting that life is different for people who think in metaphors. Having developed a means of measuring metaphoric thinking style among students, they found that people rate neutral words as more pleasant when they’re printed in a white font than in a black one (evidently, none of their subjects had ageing eyes which renders light print virtually impossible to read); that among those prone to metaphorical thinking, the more sweet food they’d eaten, the more sweet their interactions with others (presumably within limits, I’m not terribly sociable if I’m feeling sick); and that those with a stronger metaphoric thinking style showed greater insight into the emotions of others. As you can see, aside from the fact that many metaphors are actually clichės, I’m a little sceptical about this research but, not having read the full report in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, I’m not in a position to argue.  A retired French police inspector receives a letter from a woman claiming to be his daughter. A Japanese law professor is thrilled when the little girl he lives with addresses him as Father; how can he tell her that her real father is in jail? A self-centred writer who steals, not just others’ stories, but their entire identities. A father travels from the mountains to leave his daughter in the city as a rich man’s concubine. A double, or triple, agent in the Algerian independence movement, who is even prepared to deceive his wife. The perfect ingredients of a short story collection? No, this is a novel. It’s a novel composed of stories within stories within stories, like matryoshka dolls, as Tadashi Omura collars Auguste Jovert to offload the tale of his adopted daughter and his increasingly unreliable friend, Katsuo. Yet, unlike those Russian dolls, the stories don’t fit neatly one inside the other as we jump back and forth between France, Algeria and Japan, moving in time across four decades at the end of the last century. Nor, although well written, are they sufficiently distinct in style or genre, like David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, to astound us with their brilliant audacity. And while the novel provides a rationale for the structure in terms of the Japanese saying: If you want to see your life, you have to see through the eyes of another  Blackberry and apple crumble Blackberry and apple crumble While I take great pleasure in my ability to harvest fruit and veg from my garden, I don’t get particularly excited about cooking it. As I couldn’t let it go to waste, I’ve been rustling up some strange concoctions of beetroot, courgettes and beans lately and rushing to put them on the table before it gets too cool to dine in the garden. Cordon Bleu it’s not! I’m hoping my response to Charli Mills’ latest flash fiction prompt won’t also come out as a dog’s dinner. Looking for inspiration for my 99-word food story, I turn to the novels on my physical and virtual bookshelves. Consistent with my miserablist inclinations, there’s a dominant theme of the problems that food or its lack can bring. In Shelley Harris’ novel, Jubilee, a boy’s divided loyalties to his white friends and Asian family is played out in his response to the food his mother plans to cook for a street party in 1970s Britain. (You can click on the link to find the quote.) One of the enduring images in Alison Moore’s debut, The Lighthouse, is the way in which, on a catered walking holiday along the Rhine, the main character consistently fails to get the food he has paid for. Although Lewis, the central character in her second novel, He Wants, is forced to endure fewer physical privations, his food is unsatisfying because it’s not what he actually wants.  "Thornfield" in Jane Eyre "Thornfield" in Jane Eyre I’ve said it before and no doubt I’ll say it again: I love the webbiness of the World Wide Web. I love writing posts that link to other posts, both mine and other people’s, even as I worry that those phrases picked out in blue might impede the reading process. Even when I’m not forging links across the Internet, I enjoy rooting for commonalities, such as those between the novels of those writers featured in my debut novelists Q&A’s or plucking from my bookshelves novels on a specific theme, such as water or transgenerational trauma. (You can see how it gets obsessive and it’s little wonder my posts take so long to write.) Yet I’m much more cagey bringing different spheres of my own life into the blog. Yes, I’ll prattle on about gardening and make oblique references to the pleasure I get from singing in a choir. But until I started my series on fictional psychologists and psychotherapists, I kept my professional background entirely separate from my identity as a writer and, even now, the more structured and formalised are the alternative universes I occupy, the less comfortable I feel about providing a portal to them here.  Well, the challenges are mounting: the prompts for 99-word flash fiction are announced on Wednesdays and bite-sized memoir every Friday afternoon. This week it’s travel horrors for flash and childhood jinks and japes for memoir – or is it the other way around? My secret¹ ambition is to write a piece that satisfies both simultaneously but, until I get there, I’m making do with incorporating my separate responses into the one post; it gives me another excuse for navel-gazing on the writing process from memory to memoir or not. Time was when I loved to travel, although now I much prefer to stay at home. But I have lots of cherished memories; I even have a stack of travel diaries I could use to check my facts. Charli’s prompt sparked off a stream of reminiscence, of thrills and spills and moments of, if not quite terror, some pretty dodgy stuff. Were I better raconteur, my travels would make for some great dinner-table storytelling, but my adventures have made only a rare appearance in my fiction and, when they did, I got confused as to what was memory and what imagination. When it came to my 99-words I was overwhelmed with possibilities, yet none seemed strong enough to demand their moment on the screen. Charli²: But it’s fiction, you’re allowed to make things up! Annecdotist: Yeah, but somehow I don’t want to this time; I want a story that stays faithful to the things I’ve seen and done. Lisa²: Ha ha, you’re being converted to memoir. Annecdotist: Only for this particular topic. In the end, an idea bubbled to the surface and I grabbed it before it could sink back down again and another take its place. I don’t know why it chose me, but here it is: I was scared as you were, believe me, but I smothered my anxieties with thoughts of tulips, van Gogh and canals as we bedded down with the down-and-outs in a dusky recess of the shopping mall. A perfect plan in daylight: a lift halfway to Amsterdam. We’d pass the early hours in the waiting room and catch the first train out. No-one mentioned that the station closed its doors at night. The police beamed torchlight across our faces. I thought they might relax the rules for two sisters, strangers to the city, but they ushered us into the night.  Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin my story of how I helped bring an Indian elephant into the English countryside and learnt something about storytelling in the process. Once upon a time Chamu told me about a guided walk she was planning in the Peak District. The aim was to use story to promote diversity within the national park and the walk would be integrated with the local celebrations for birthday of the Hindu god, Ganesh. Well, I thought, what could be better than walking and storytelling? I jumped at the chance to help out. Although I knew a little about the elephant-headed god from my travels in India many moons ago, these weren’t exactly stories I’d heard my mother’s knee. What if others were more familiar with the story than I was? Would I be able to engage people? What if I forgot my lines? Of course, I needn’t have worried. Thanks to Chamu’s support and a lovely group of tolerant walkers, I had a fabulous time telling my two stories, as you’ll see from the pictures below, and from others on the Hindu Samaj website. The experience got me thinking about the differences between story writing and storytelling. Although I often read my fiction aloud to check for stumbling blocks, telling a story without a script to an audience is another matter altogether. As a reader and as a writer, I treat adverbs with suspicion and every adjective has to earn its keep. Yet the oral form has a baroque feel to it, bustling with verbal curlicues, never using one word when half a dozen will do. Repetition, cliches, It came to pass and In due course – I welcomed them as joyfully as I attempt to edit out each just and quite from the written form. It wasn’t the presence of two delightful children that made me spout such archaic and nursery-style phrases; they seemed appropriate for the story to flow.  Relaxing into the role, I began to tell the story physically: modulating my voice; exaggerating my facial expressions; making judicious use of pauses. I don’t have an extroverted bone in my body, but I couldn’t help falling into the rhythms and performing. This will be no surprise to those familiar with reading bedtime stories, but to me it was a revelation, and I’m looking forward to doing it again at the end of August next year, only better. (If you watch the video below, you'll see there's lots of room for improvement.) If you'd like to come, the details will be on the Ranger walks calendar. If you've been paying attention, you might have noticed I've delivered all the posts I promised for October (gold stars all round). For next month I hope to bring you the fourth instalment in my series on fictional psychologists and psychotherapists; a look at internal obstacles to achieving one's personal and fictional goals inspired by my Q&A with Anthea Nicholson, as well as my recent post on character motivation; and why I'm raving about a small book of psychoanalytic case studies. I've also got posts in the pipeline on writers' routines; writing in the first person plural; old-age stereotypes; leaving home; another look at rhythm and my love affair with allotments. Hopefully there's something you'll want to come back for. If you're still wondering how the elephant god got his head, you can read a précis of the story here:

The video picks up the story halfway through, when Shiva has chopped off the head of Parvati's darling boy and is sending out his bodyguards to find a replacement. Or go here for a musical version of the story.

|

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed