Nobber by Oisín Fagan

Following the collapse – through departure or murder – of the established order of sheriff, mayor and priest, a nameless outsider has stepped into the leadership gap. With the assistance of the town’s farrier, he’s imposed a curfew, while awaiting the arrival of his business partner, who will collect the dead bodies to grind their bones into a fertility tonic to trade with the Gaels.

Debarred from leaving their windowless hovels, the townsfolk languish in darkness and stifling summer heat, along with their moribund relatives and putrefying dead. The situation is almost beyond crisis when de Flunkl and his crew close in.

This quirky and captivating novel is populated by grotesques, their minds warped by sickness, fear, claustrophobia, greed and unfulfilled desire. But the author’s compassion for his characters, especially the women (including one with what seems to be postnatal depression), stops short of making them cardboard cut-outs. While the tone is light and playful, and the background violent and visceral, these people grapple with questions of morality and meaning, including what has caused the plague.

Oisín Fagan’s novelistic debut is a darkly entertaining tale of pestilence, madness and land seizure for which publishers JM Originals, who provided my review copy, seems a most appropriate home. If you like intelligent bonkocity, this is for you!

| I’ve also created characters grappling with questions of morality and meaning in my short story collection, Becoming Someone. You can see and hear me read the opening of “Telling the Parents” here. | |

To Calais in Ordinary Time by James Meek

At the same time, a young serf, Will Quate, also departs her father’s estate, away from a predictable marriage and towards adventure. He’s been granted permission to join a band of bowmen journeying to Dorset to board a boat for Calais, to fight to protect the port from being reclaimed by the French. The troupe of ruffians is loosely under the command of Haket, who unfortunately did nothing to prevent the brutal rape of Cess, a young French woman, who’s travelled with them for the last two years. Also attached to this group, albeit more freely, is Will’s childhood friend, Hab, who, having stolen Bernadine’s wedding gown for his alter ego, Madlen, is now an outlaw.

As the band travels south, the plague – to some, until then, believed to be a falsehood perpetrated by the church to sell more relics and remedies – is moving north. Thomas Pitkerro, a Scottish-born proctor who has made his home in Avignon but recently seconded to Malmesbury Abbey, is foisted upon the group: a priest being more use than a doctor and a Latin-speaker with clerical connections the next best thing to a priest.

Disparate characters journeying together through medieval England, interspersed with stories and bawdy humour, is reminiscent of The Canterbury Tales, but Meek’s language isn’t Chaucer’s. Nor is it contemporary English. The archers speak a Cotswold dialect, while Bernadine’s speech is strongly informed by French and Pitkerro’s by Latin. If the reader feels challenged, as I was, she’s not alone, as communication between the characters is interrupted by requests for clarification of certain words, amusingly often the words the contemporary reader most easily understands.

These linguistic differences emphasise the cultural differences between the different groups, and the gradual dawning of impending mortality beautifully illustrates the conflicting worldviews. Yet by the end, among the survivors, there’s a mutual respect as those who began the book as caricatures mature into rounded human beings. It’s a heartening conclusion in our currently polarised country, as well as consistent with recent developments in social psychology.

James Meek’s eighth novel is an impressive, if challenging, linguistic achievement, exploring power, belief, gender, love and misogyny set in cataclysmic times. Thanks to publishers Canongate for my review copy. I wouldn’t be surprised to see it nominated for the Booker prize.

Additional musings

| | Although forced-fed Catholicism as a child, it took me a while, and a second novel on the subject, to fully appreciate the characters’ terror of dying without confessing their sins to a priest, thereby condemning themselves to eternal damnation. There’s a more contemporary attitude to confession in a story from my collection, Becoming Someone. Here’s the opening of “Four Hail Marys” |

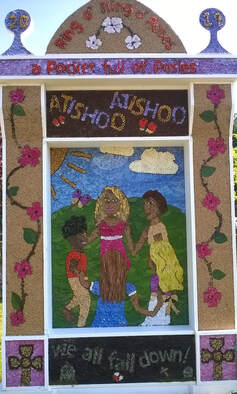

| When I think of the plague in Britain it’s 300 years later, when a village in the Peak District famously and generously sealed itself off from its neighbours when the pestilence arrived from London in a bale of cloth. This image is of a well dressing created by the children of the village this year, commemorating the plague in the form of the nursery rhyme thought to be derived from that tragedy. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed