| I desperately wanted my third novel, Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home, to be published this year. For one thing, I like the ring of 2020. For another, I’ve been working on it long enough. Begun with three character sketches in autumn 2014, I completed an 80,000 word first draft in January 2015 and, after various ups and downs, including ballooning to 130,000 words, had it ready for reader feedback three years later. |

A deadly virus

My novel is about mental illness, not physical illness but a character born in 1919, as Matty is, must know about the scourge of the Spanish flu. Especially a girl who doesn’t know the full story of what killed her father. Fast-forward to the late 1980s/early 1990s, and anyone working in health or social care, such as my second point-of-view character, Janice, would be horrified by the spread of the mysterious, and initially unstoppable, virus HIV. As a fledgling social worker, Janice is determined to put the world to rights. When life for the longstay psychiatric patients doesn’t improve fast enough, she considers shifting to another specialism:

Their predicament mirrored Matty’s: shunned by society, and their families; robbed of their futures; punished for having sex. Did AIDS patients need her more because they died physically, in addition to socially and psychologically?

Self-isolation

Henry, the third point-of-view character, spends some time in self-isolation, not because the virus he contracts is particularly lethal but because he lives alone and is too sick to drag himself to work. Henry knows it’s

barmy to bother the doctor with a virus. Medicine was impotent in that regard.

but he needs a sick note for his employer. Emerging from self-isolation is disorientating:

the ground rocked beneath his feet. He’d been at sea and hadn’t recovered his land-legs.

Online connections

Henry is a laggard regarding new technology; as a payroll clerk in local government, he’s resisted the computerisation of a system he devised back in the 1970s. To his manager’s intense frustration, he’s refused to attend residential training on the off-chance that his sister – whose return he’s awaited for half a century – should turn up to an empty house.

He might have chanced it if a computer could magically locate his sister. But a glorified calculator-cum-typewriter couldn’t succeed where letters to editors in five continents had failed.

Alas, poor Henry! If only he could have foreseen how much we’ve come to rely on digital technology, and how vital it’s been for maintaining contact with friends and family even before the pandemic had us on lockdown.

High hopes

Despite the lack of response to his letters to newspapers around the world, Henry remains optimistic he’ll find his sister. But it’s not only a computing course he’s missed out on while he’s put his life on hold. Janice could also be considered overambitious in her confidence that she can substantially improve Matty’s quality of life. One of the novel’s themes is the narrow line between high hopes and delusion, yet only Matty, who believes the hospital where she lives is her mother’s country estate, is mentally ill. In one of its previous incarnations, this novel was called High Hopes.

Just as in the novel, excessive hope and optimism might be detrimental in our current crisis. Some of the leaders who have been tardy in acting to contain the virus, such as Boris Johnson and Donald Trump, are also politicians with an excessively can-do style of presentation and disregard for the facts. Let’s hope their apparent optimism hasn’t risked too many lives, although clinician deaths, ostensibly due to inadequate personal protection equipment, is an outrage.

No point

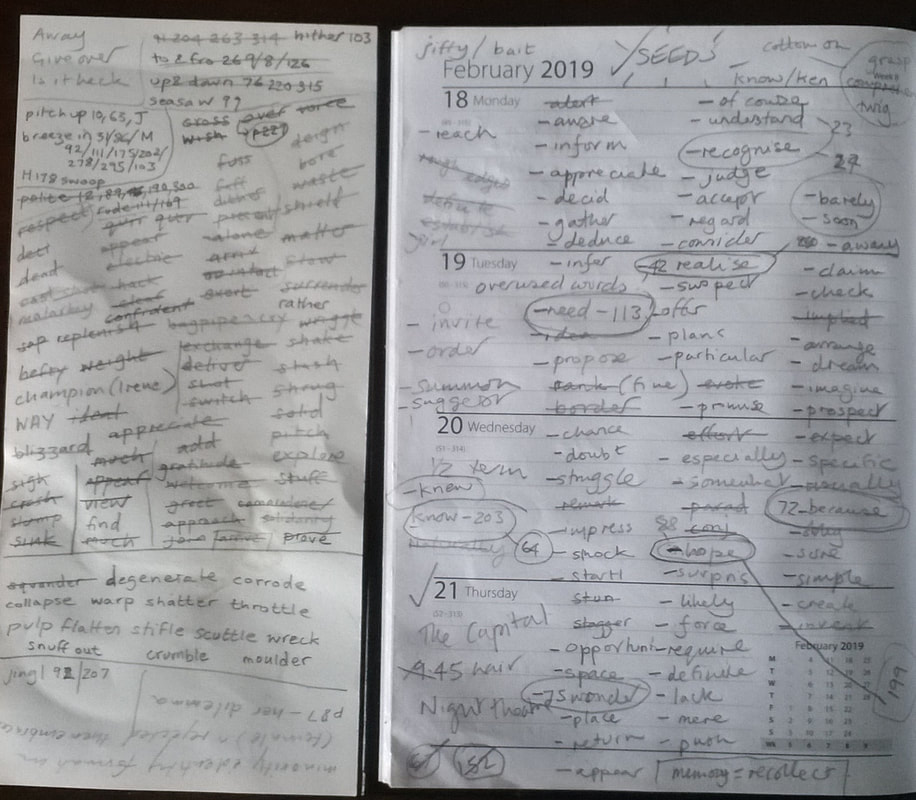

| We try to keep our hopes up in order to keep going and ward off despair. But these are anxious times, and we’ll all have our low points. So far, my worst time was two weeks ago, the day after the closure of schools and pubs and restaurants and a couple of days before the UK went into lockdown, when things felt uncontained and chaotic, and I grieved the loss of ordinary life. Around that time, ploughing through my list of potential word echoes, I waged war on the 56 occurrences of point in my manuscript (not only as a standalone but embedded in other words such as appointment and disappoint). As I was wondering whether not only the meticulous editing was pointless but the whole enterprise of fiction had no point, I managed to cut the occurrences down to 34. |

Life in lockdown means being bombarded with suggestions of how to fill that extra time. While I’m already far too busy to learn Lithuanian and haven’t been able to buy the flour to bake more than a basic loaf, I do recognise the value of purposeful activity in maintaining our mental health. In the early years of the asylum movement, patients were supported to keep active, but overcrowding meant that by the time of Matty’s admission in the late 1930s, they had little to occupy their minds. Deprived of even basic choices, they became disabled not only by mental illness but by institutionalisation, which community policies aimed to rectify.

Bathroom behaviour

Who would have predicted that a virus that targets the lungs rather than the digestive tract would have people fighting over packs of toilet paper in the supermarket aisles? Well, maybe Matty would: having lived in the slums she’s rather impressed with “a bathroom and separate flushing lavatory with paper that didn’t leave newsprint on your bum” when she visits a posh house at the age of twelve.

Henry might appreciate the need for social distancing, as far as we can judge from his avoidance of shaking an older man’s unwashed hand. Of course, you’d expect a toilet scene or two from an author who celebrates fictional toilets.

I wonder if I’d have found another set of echoes if I were living through a different crisis although, at the top of my head, I can’t remember any references to apocalyptic fire or flood. But maybe I haven’t looked hard enough.

What do you think? Have you found any interesting echoes of our current crisis in your own writing?

| Onwards to this week’s flash fiction challenge: pizza. Pizza? Charli must be missing her comfort food. As a child, I’d come across pizza pie in books, without knowing what it was and, living in a small town, I didn’t find out until eating at pizzerias at university aged eighteen. But, by the late 1980s, when my novel begins, pizza was commonplace in the UK such that, when Janice meets up with her friends from her social work training, they get a pizza delivery. I’ve drawn on that scene, part of the subplot of Janice’s feelings about having been adopted, for my 99-word story: |

Janice’s gaze swept across the debris: grease-smeared delivery boxes; glasses mottled with burst beer-bubbles; cigarette butts shipwrecked in olive oil. She didn’t begrudge her friends their gallows humour, but that baby was a case to them.

A wailing baby, a washed-out mother, a blaring TV. A typical home visit. The punchline – pun intended – was the mother screeching into the pram, “Tom and Jerry! It’s your fucking programme!”

“A two-month-old propped up to watch a cartoon cat take a mallet to a mouse.”

Janice nibbled a shard of pizza crust. “I’m thinking of tracing my birth mother.” The laughter stalled.

Subscribe to my newsletter for the chance to win one of three copies of Matilda Windsor Is Coming Home plus get an e-book of prize-winning short stories to read right now.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed