| Upstate New York in the early 1970s and George and Catherine Clare move into a farmhouse at the foot of the hill. Previously, the hub of a working dairy farm, the house feels haunted by the woman who held it all together and, unbeknown to Catherine, died along with her husband in the master bedroom. Because of this unhappy legacy, the Clares got it cheap, which causes some resentment in the close-knit community centred on Chosen, the nearby town. Yet George, a professor of art history at the local college, charms them initially, but it’s Catherine, a former artist and now stay-at-home mother of three-year-old Franny, whom they take into their hearts. So everyone is shocked and saddened when George comes home one evening to find her with an axe through her head. |

Welcome

I started this blog in 2013 to share my reflections on reading, writing and psychology, along with my journey to become a published novelist. I soon graduated to about twenty book reviews a month and a weekly 99-word story. Ten years later, I've transferred my writing / publication updates to my new website but will continue here with occasional reviews and flash fiction pieces, and maybe the odd personal post.

|

4 Comments

It’s not unusual for a novel to tell a story from different viewpoints, or from the same point-of-view character at different points and/or places of their lives. Some writers take this a stage further, structuring their novels as a series of related but stand-alone short stories, gradually building up to a whole. Examples among my reviews are This Beautiful, The Green Road, Sophie Stark, Prosperity Drive and Vertigo. Now I’ve found a couple more, in which the disparate narratives combine to create a sense of place.

What does the working-class child aspire to? In my case, I couldn’t dream of joining a middle-class profession I’d never heard of. Nor, even though I was addicted to writing from the start, did I believe that someone like me could become an author. Books never seemed to be based in the places with which I was familiar: they were set in boarding schools rather than comprehensives; in country houses rather than a small semi-detached; in cities rather than small industrial towns. So how could I resist a novel set in my birthplace, the small northern town from which my odd accent derives? As if that weren’t enough, I’m offered a novel set where my parents grew up, a similar down-at-heel out-of-the-way place where I had my first restaurant meal. Sixty miles separates these two towns, as well as some breath-taking countryside, as depicted in The Wolf Border, one of my favourite reads from last year. But Workington and Barrow don’t have the beauty of the Lake District. Thanks to Vintage Books and Legend Press, I had the chance to discover whether they could nevertheless shine on the page. I’d be interested in your thoughts on using real places as fictional settings.

It’s August 1985, and Ananda, a student of English at the University of Central London with aspirations to be a poet, has a whole day to fill. We follow him reluctantly get out of bed, fret about the neighbours’ noise, miss his mother who has recently returned to Bombay, attend a meeting with his tutor, and hang out with his equally eccentric uncle, Rangamama, as they separately reminisce and bicker about their lives. Their territory is Bloomsbury, Hampstead and Belsize Park, a world of disappointing Indian restaurants, public transport, and potentially racist drunks. Inveterate outsiders, not just in London but in Asia, too: their Sylheti Hindu heritage having been twice rebranded (first with Partition, then with Bangladeshi independence) and leaving a legacy of “Indian” restaurants and the revered poet, Tagore. Desperately unhappy, the two men cling to each other despite their differences, Ananda possibly seeing his empty future in his uncle. It’s hard to know what to make of a novel comprised of all the minute quotidian detail that most novels would cut out. There are touches of humour, and I especially enjoyed this exposition on the lack of reference to lavatorial necessities in Western film and literature (p128-9):

A severe cold has meant very little writing in the last few days, but a copious amount of reading (completing my reading “challenge” of 100 books in the year), albeit with not a great amount of depth. These three short reviews of novels about three very different women’s quests for a life, and a mind, of their own is part of the result.

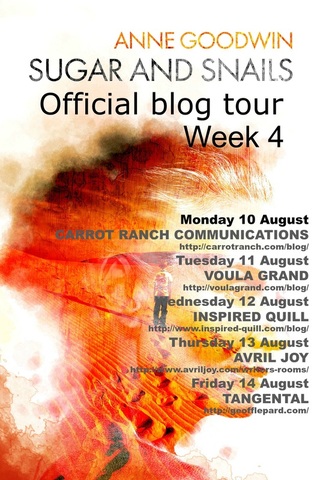

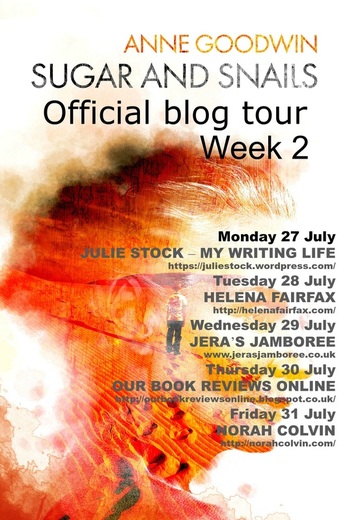

Pilgrim Jones has done something shameful: crashed her car into a bus stop and killed three young children, although she has no memory of doing so. Did she swerve to avoid the dog and lose control of the vehicle or, consumed by anger and self-pity after being dumped by her human-rights lawyer husband, was she reckless? Certainly her neighbours in the small Swiss town of Arnau consider her a child murderer and, despite the sympathy of the police, she realises she has to get away. With no particular plan, she flies to Tanzania and, dropping out of a safari, pitches up in Magulu, a shabby village on the road to nowhere, with one bus out a week. Here she finds herself a world away from her former travels with her ex-husband, from her role as a diplomatic wife. Here, where the doctor has no medicine, the policeman no power to uphold the law, violence or the threat of it is ever presence at the periphery of her vision (p82/83):  It’s been another hectic week on the blog tour: sharing the novels that have helped me find a mind of my own with Urszula Humienik; examining how contemporary novels feature scientific research with Gargi Mehra; talking attachment with Safia Moore stemming from my character’s difficulty in “telling a story about when you were a little girl”; confessing and commiserating with Clare O’Dea regarding our shared difficulty in articulating what our novel’s about; to come to port on Friday with Lori Schafer to address the question of how much my novel might be autobiographical. After my weekend in a virtual California, I’m heading northward today to join lead buckaroo, Charli Mills on her fabulous Carrot Ranch in Idaho. She’d already set my place at the table with this lovely introduction on her blog. I’m heading back to the UK for the rest of the week, stopping off first with novelist and psychologist Voula Grand, who was the first to feature in my series Psychologists Write, to explore a shared interest in transgenerational trauma, both on and off the page. Then it’s a second guest post (the first, on Day One of the tour, being on debuting as an older author) with my publishers, Inspired Quill, to reveal my responses to the thoughtful questions put to me by one of the team, Hannah Drury. With all this travelling I wonder if I’ll have time to tidy up before Thursday, when I’ll be showing everyone around my Writers’ Room, courtesy of novelist, former prison governor and Costa Short Story Award winner, Avril Joy. Friday, I’ll be hot-footing it to London to join novelist, blogging addict and reader of an early version of Sugar and Snails, Geoff LePard, for a post on how walking facilitates my writing with, hopefully, a few photographs of the walk that features in my novel. (Yikes, did he realise that’s the day he launches his second novel, My Father and Other Liars, or is his attention to me an excuse to avoid a launch party?)  If I was breathless last Monday, announcing Week 1 of the Sugar and Snails blog tour, I must be on the verge of a swoon this week as I begin another round of visits. The first week has gone brilliantly (you can catch up with those first five posts via the links on my blog tour page), so how could I not be excited about the second? I start today under Julie Stock’s Author Spotlight, with a piece about setting part of my novel in Cairo. As a writer of contemporary romance from around the world, Julie has a particular interest in the challenges of setting fiction in real places, the subject of her own post on Susanna Bavin’s blog this week. Tomorrow, Helena Fairfax is interviewing me about where my own life is set, among other things. Helen lives in an interesting place herself, the UNESCO World Heritage Site and former mill town, Saltaire, which you can discover more about in her fascinating post. Then I’m off to chat with my namesake, Shaz Goodwin on Jera’s Jamboree. With her day job as a school Inclusion Lead, I was interested in her interest in novels that tackle a social barrier, as Sugar and Snails most definitely does. On Thursday, I’m on Our Book Reviews discussing the various transformations of my novel from its initial inception as a story of masculinity across three generations. This post arose out of a Twitter conversation after Mary, one half of Our Book Reviews, read and reviewed an advance copy. Obviously, I was delighted to be invited back. Finally, Friday sees me in Australia, quite fittingly discussing the theme of friendship in the novel and in its realisation (extending the theme of my previous post on gratitude) with one of my dearest blogging friends, Norah Colvin. As Norah has already hosted me once before, I know the tour bus will be safe to leave there over the weekend until I get behind the wheel again on Monday.  I’m generally not in favour of “update” posts, but I can’t ignore the perspective shift since I posted five days ago. As of last Thursday, I’m a published novelist, and enjoying it immensely. With each review (six to my knowledge so far), with each supportive tweet at #SugarandSnails, I’m claiming more of my authorial authority. I’m even infiltrating the more traditional media, with a feature on Sugar and Snails in the Lincolnshire Echo and a nerve-wracking but not too dreadful outing on BBC Radio Nottingham (my bit is at about 2.15 p.m. and the link expires in about three weeks). The highlight of the last few days was, of course, my Nottingham launch party, which I’ll be sharing more about in due course. But in the meantime, there’s this lovely and unexpected post on the event from The Mole, the other half of Our Book Reviews.  Two twelve-year-olds from separate states are abducted and kept for six weeks in a cabin in the woods. The girls are strangely compliant, fearful of what might happen but excited to be plucked from their neglectful parents and dreary lives. Spelling-bee champion, Lois, and beauty-pageant veteran, Carly-May, crave adult attention, and are thrilled to find themselves chosen, competing and cooperating for the approval of their kidnapper, the mysterious Zed. Decades later, they know they’re damaged by the experience, although unsure exactly how. Lois has become a university lecturer, specialising in nineteenth century English literature, with a secret side-line as a writer of popular fiction. Carly-May has reinvented herself as Chloe, an actor too pretty to be taken seriously, still hankering after a more intellectually challenging part.  Nancy and Bernadette have spent every summer at the remote farm where their mother grew up. Despite the sullen nature of their uncle, Donn, and the religiosity of their aunt, Agatha, who returned from training to be a nun to keep house for him, it’s an idyllic place to a ten and twelve-year-old from London. But the bond between the sisters is weakening, as Nancy, now at the comprehensive school, wants to play at being a grown-up. And there are far darker forces at work than sibling rivalries. For in Northern Ireland during The Troubles, the English are unwelcome in certain parts and a lonely farm has every chance of being co-opted into the undercover war. Thirty years later, having barely spoken to each other since childhood, the sisters return to the farm with their families on the pretext of seeing the place for one last time before it’s sold. It starts badly: Nancy’s American husband is both overly chatty and bored; Bernie is critical of her sister’s hypervigilance around Nancy’s fourteen-year-old son, who appears to have some kind of attention-deficit disorder (p79):  Lulu Davenport is the proprietor of Los Rocques, a clifftop hotel on the Mediterranean island of Mallorca, frequented by a certain type wealthy Brit who holds themselves aloof from the package-tour hordes. It’s also a popular hangout for the teenagers who spend their summers on the island, roaming freely after months of more orderly education abroad. For almost sixty years, Gerald Rutledge has lived in a small house just a kilometre away from The Rocks (as everyone calls it), but he’s rarely set foot on the premises. It’s not just because, having married a local woman and made his living from the land, he’s more assimilated into the Spanish community, but also because he’s persona non grata to Lulu following their brief and calamitous marriage only a few years after the end of the Second World War.  Sorting through the effects of her beloved grandmother, Mariam, shortly after her death, British journalist, Katerina Knight, discovers a wooden spice box containing a journal and stack of handwritten letters. The documents are written in Armenian, a language which neither Katerina nor her mother understands but, on holiday in Cyprus, Katerina meets a handsome young man who offers to translate them. Mariam’s scribbles tell of relatives lost to slaughter and exile in the 1915 Armenian genocide, of a fortuitous rescue by an English couple and a country childhood ending with another lost love. Meanwhile, Gabriel, an elderly Armenian living in Nicosia, exiled a second time with the partitioning of Cyprus into Greek and Turkish sectors, is bemoaning his granddaughter’s engagement to a man from outside the community, perceiving it as a betrayal of her origins, as cultural genocide, although one of his drinking friends advises tolerance (p175-6): ‘Let go of the past, my friend. All that stored up resentment isn’t good for the soul.’ ‘The past is not like water in a toilet bowl. It can’t be flushed away. It’s a septic tank growing more rancid by the day.’ The reader discovers before he does Gabriel’s link to Mariam and Katerina, and from that point the novel is driven by the question of whether these characters will finally connect.  The Haitian earthquake of 2010 makes an unusual setting for a romantic comedy, but this novel manages to beautifully balance the devastating impact of the unexpected seismic event alongside celebrating bonds of affection and the resilience of the human spirit. A love triangle between twenty-year-old artist Natasha Robert; her new husband, the president, forty years her senior; and Alain, the lover she has abandoned in the hope of escaping the confines of her native country. The novel opens with a bang in the rubble of the airport, with the reader sharing Natasha’s initial disorientation; only moments before, she was climbing the steps to the plane that was to take her and her husband to a better life in Italy.  On March 25th, Greek Independence Day, John Petrakis, distinguished professor of ancient history, is booked to give a lecture to the Aegina Historical Society. He never makes it: shot through with the bathroom window of the house of one of his dearest friends while taking a shower. His brother, Constantine, despite his lack of filial sentiment and despairing of the police’s tardiness, recruits George Zafiris, private detective based in Athens, to investigate the murder. As George tries to unravel the mystery, another of his cases is becoming increasingly murky, with the unexplained death of a politician engaged in an extramarital affair. The family in the world: The Winter War by Philip Teir and The Lightning Tree by Emily Woof15/1/2015  I’m delighted to bring you reviews of two novels published in the UK today which feature couple and family relationships within a wider sociopolitical context. The Winter War* follows a liberal, middle-class professional Scandinavian couple and their two adult daughters over the course of one winter. While this is a period of change for the family, the pleasure of this novel is less in its plot than in its beautifully drawn characters* and searing sardonic wit*. Max Paul is a Finland-Swede*, a sociologist approaching sixty, living off his reputation as a public intellectual, given an ego-boost when a former student turned journalist requests an interview: One important criteria for all research was that it had to be possible to explain the basic ideas in a simple manner. A good doctoral dissertation could be comprehensively summarised over lunch. Taking this to extremes: a good researcher should, in principle, be able to speak with such enthusiasm that his words could function as a series of pick-up lines. (p74) His wife feels ground down by his emotional neglect and burnt out at work in the human resources department of the Helsinki health service: I do enjoy exploring unexpected links between the novels I’ve been reading. A gritty story of the real-life dangers faced by illegal immigrants on the streets of contemporary Cape Town seems a world away from the remote homestead in 1920s Alaska in which Eowyn Ivey’s modern fairytale is set. Yet, apart from being debut novels and the happenstance of my reading them in sequence, both are stories of survival with an unusually pale-skinned girl at their hearts. In addition, The Snow Child also gives me an opportunity to acknowledge the writing of a couple of other bloggers whose support I cherish, while Zebra Crossing has served as the inspiration for my response to Charli Mills’s latest flash fiction challenge.

It’s some years now since I had any interest in holidaying abroad – or venturing on holiday at all, if I’m entirely honest – and my last trip outside Europe could well be part of the reason. This was a fascinating botanical tour of Madagascar but, because we were focused on the flora, our interactions with the local people were somewhat limited and often unsettling to my woolly-liberal constitution. I wrote about this in my post On Memory and Imagination on the publication of my short story, Silver Bangles, a fictionalised account of an incident on that trip that brought the disparities in wealth between the locals and the tourists into sharp relief. A similar encounter provided the material (if that doesn’t sound too disrespectful) for my water-themed flash. But a third uncomfortable event from that holiday – in which I dithered about donating my sunscreen lotion to a family with albinism seen from the comfort of our bus in a remote village – hasn’t yet made it into my fiction.  It was my wedding anniversary last week and, despite shying away from romantic fiction, I thought I ought to read a novel with a heart at its centre. Thus Jill Dawson’s novel made its way to the top of my TBR pile and, because of its thematic parallels, Rebecca Buck’s novel followed on. Patrick Robson, a history professor with thirty-odd years of over-straining both his literal and metaphorical heart, wakes up in hospital following major surgery with his ex-wife at his bedside. Two hundred years apart, two teenage boys experience their sexual awakening under the wide skies of the Fenlands, and discover how the odds are stacked against those not born into wealth in cash or land. What connects the three main characters is that Drew Beamish was carrying a donor card when he was killed in a motorcycling accident, and Patrick has received his heart, while Willie Beamiss, only just escaping hanging or deportation for rioting, is one of Drew’s ancestors, and commemorated in the local museum.  Do you ever ponder your dependence on the modern world and wonder how you’d adapt if it came to an abrupt end? My ability to grow my own food, knock up a functional mortise and tenon joint and navigate across country on foot might provide me a modicum of security, but I’d be useless without my glasses to see where I was going and clueless at working out how to make electricity from scratch. And who knows, until we find ourselves in a situation that demands it, whether we have the mental and physical capacity to kill another human being to save our own skins? I don’t know if it’s surviving trauma that evokes such apocalyptic philosophising or whether it’s integral to the human condition. There’s certainly an attraction in the theme for writers of fiction; I’ve just counted seven novels on my bookshelves that speculate on the impact on human society of devastating global pandemics or massive climate change. You might have even more, so how do I persuade you that Station Eleven is the one you really must read? I received my proof copy several months prior to publication and, although I was interested in the premise, I wasn’t in a great hurry to read it, perhaps put off by the hype. It’s described as perfect for fans of Hugh Howey, who I’ve never read, and Margaret Atwood, who I have, a lot. I can detect the similarities to The Blind Assassin and Oryx and Crake, both books I loved, but I’m not a fan of fanfiction. In a fair world, where writing was judged on its merits, Emily St John Mandel wouldn’t need to be compared with the literary greats. She is an excellent writer in her own rights. More fool me for not picking it up sooner.  When we live in a world that includes neo-Nazis and Holocaust deniers, it’s incumbent upon the rest of us to ensure that the death camps aren’t forgotten. But how do we acknowledge such a horrific and shameful aspect of European history in a way that is truly authentic? How do we avoid approaching it in a way that is either overintellectualised or overly sentimental, or filtered through our own cultural identities as victims, perpetrators, collaborators or disengaged bystanders? Do we force-feed it to children too young to understand (the subject of Elissa Cahn’s flash fiction, On Behalf Of the Class, as well as one of my own eternal WIPs)? Do we turn a blind eye to the transgressions of the descendants of the survivors on account of their culture having been persecuted so much? Do we use it to work through our individual issues of terror, trauma, cruelty and guilt? How to bear witness to the Holocaust is the subject of Peter Matthiessen’s final novel (he died earlier this year), In Paradise. One hundred and forty people – nuns and priests, Jews, Buddhists, survivors, academics, Germans, Poles, Americans and Israelis – gather at Auschwitz in the late 1990s for a week-long retreat. They sleep in the dormitories that previously housed the camp guards, they file past the piles of hair and baby shoes in the museum, meditate sitting cross-legged on the selection platform before a meagre lunch of rough bread and thin soup, and assemble in the auditorium in the evenings to give voice to their individual and collective experience. We follow this from the perspective of Clements Olin, an American academic of Polish descent, who has joined the retreat to facilitate his research into the life and writings of Tadeusz Borowski, a survivor of the camp who committed suicide at the age of twenty-eight by sticking his head in the gas oven. Little by little, Olin acknowledges a more personal motivation for being there as he uncovers uncomfortable aspects of his own family’s history. Faced with such horror, who wouldn’t shy away? This Is the Water and The Cold Cold Sea ... with a quirky style and some reflections on structure31/7/2014  I didn’t expect to be dipping my toe in the water again so soon after Waiting for the Rain, but the coincidence of two new novels swimming to the top of the TBR pile has compelled me to add them to Annecdotal’s growing stream of water-themed fiction. Published today and tomorrow, both novels evoke the dangers that lurk in the water through the pain of losing a child and the question of how far a parent will go to safeguard their family. This is the water. This is the text: letters forming words, words forming sentences, sentences making paragraphs to convey the story of the pool and the girls and boys who swim in it and the parents who ferry their children there. This is Chapter One where you enter the minds of swim moms ultracompetitive Dinah and beautiful but weary Chris. This is Annie who will lead you through the chlorinated water where the killer also swims. This is Annie, confused by her brother’s suicide and her husband’s emotional distance, corsetting her girls into their skin-tight racing suits and deliberating over overpriced energy drinks. This is Chapter Fifteen. This is you still ambivalent about the “unique narrative style”, wondering if it’s slowing the pace unduly, wondering why this novel is described as a thriller. This is Annie’s husband, Thomas, reading a newspaper report about a girl with her throat slit letting you see at last how well this novel fits the genre. These are the next 200 pages of moral dilemmas around marital infidelity and withholding evidence to protect one’s own skin. This is the climax where Annie’s everyday cares and concerns are meaningless as she fights for her own life and that of her daughters. This is me wondering how many other bloggers have adopted the author’s style in their reviews. This is Yannick Murphy’s fifth novel. This is the water. Will you plunge in? |

entertaining fiction about identity, mental health and social justice

Annecdotal is where real life brushes up against the fictional.

Annecdotist is the blogging persona of Anne Goodwin:

reader, writer, slug-slayer, tramper of moors, recovering psychologist, struggling soprano, author of three fiction books. LATEST POSTS HERE

I don't post to a schedule, but average around ten reviews a month (see here for an alphabetical list), some linked to a weekly flash fiction, plus posts on my WIPs and published books. Your comments are welcome any time any where. Get new posts direct to your inbox ...

or click here …

Popular posts

Categories/Tags

All

Archives

March 2024

BLOGGING COMMUNITIES

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed