| Writers are rightly interested in the unconscious as both a source of creativity and a means of revealing our characters’ unacknowledged anxieties and desires. Since Freud considered dreams the royal road to the unconscious, perhaps we should also be curious about dreams. I’m also interested in what happens when the boundary between dreams and reality breaks down, as in hallucinations and delusions, and the thoughts that arise in a hypnagogic state. How do we use these in our fiction? How do we avoid getting it wrong? |

The amazing workings of the unconscious mind

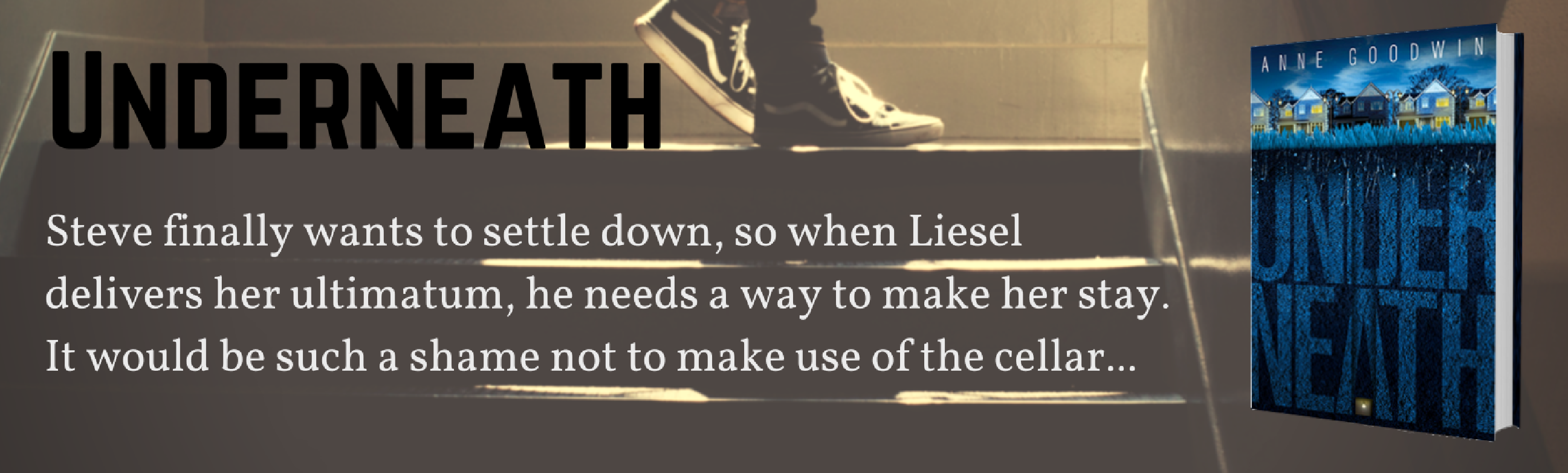

Steve, the narrator of Underneath, is strongly in denial about his vulnerabilities. But, although he’s never going to confess to the pain an absent father, it’s extremely apparent in the symbolism, some of which I was unaware of at the time of writing, as explored in my post The Dead Space Underneath.

Writers can illustrate the opposition between a character’s conscious and unconscious motivations through self-sabotaging behaviour and through body language that belies the words that come out of their mouths. And, of course, we can draw on another Freudian concept, the slip of the tongue, as I did in this 99-word story:

Speed dial

Phone clamped to my ear, I throw clean underwear into a bag. I hate to miss her birthday, but Gill will understand. Grabbing my toothbrush, I blurt out what I know.

The idiot’s done it again. I’ve got to go. There’s no-one else.

Silence at the other end. Why doesn’t she speak?

“The idiot?” A man’s voice? Offended. How could I call him instead of Gill?

“Sorry!” I cringe to think I’ve hurt him. “I didn’t mean it.”

But I did. “We need to talk about this.” Time he got some proper help. Stopped relying on me.

Fictional dreams

One thing I’d never do is to get my characters thoroughly embedded in the mire only to conclude it was all a dream. The reader who has invested time and emotion in their journey is going to feel cheated. We can all do better than that.

| I envisaged the dream sequence in Chapter 15 of my debut novel, Sugar and Snails, as a way of providing the reader with a strong hint of the secret that had had them guessing from the start. But it doesn’t seem to have worked this way: although no-one has (yet) complained about this scene; neither has anyone (as far as I can remember) said the dream functioned for them as the Big Reveal. |

If that’s the case, how do writers signal readers to pay attention to fictional dreams? One way, as Michael Grothaus did in Epiphany Jones, is to make it a recurring dream (so long as the point isn’t overly laboured so that we turn away in boredom): a reader who doesn’t get the significance the first time is offered a second – or third, or fourth – chance.

| When it came to my second novel, Underneath I kept Steve’s dreaming to a minimum. But I did want to show readers the workings of his unconscious mind. So, at a time of deep conflict with his girlfriend about her insistence they start a family, he dreams (p 141-2): |

But shortly afterwards, in a place that seems closer to reality than a dream, it’s as if he’s the baby:

I ducked my head under the duvet, drifting into a limbo between memory and hallucination. I was waiting waiting waiting but nobody came. Crying crying crying but nobody heard. Needing needing needing but nobody cared. The giant loomed over my cot, flecks of powderpuff and hairspray falling on my face. What’s all that noise? she said. You’re a bad bad bad bad boy.

Is this a dream or something else? When does a dream become a hallucination? As an extremely disturbed man intent on appearing super-rational, Steve would probably dismiss this as a dream. But an anomalous experience the following night proves more challenging (p146):

Nothing to hang on to except terror; no certainties, no thoughts. No one to save me, and hardly a me to be saved. I was wiped out, obliterated, as if the teacher had chalked my name on the board and rubbed it out. Nothing to show I’d ever existed but a dusting of white on black.

No point calling out. Instead, I should make myself small, quiet, inoffensive; merge myself with the blankness of the blackboard until the danger swept past. Yet I couldn’t hold all the bits of myself together, I was all loose pieces and unwieldy shape. I was a squiggle of lines, a tangle of barbed wire, a muddy puddle, nothing that made sense. I had no shield, no shelter, no way to brace myself against attack. I heard a lamb’s bleat, an anguished squeak: my own voice betraying me to the monsters beyond.

When, the next morning, Liesel enquires about his nightmare, he tells her (p148):

“It was like those stories you read about,” I said. “A guy gets a knock on the head and his memory’s totally wiped. Can’t even remember his own name.”

Even so, he dismisses Liesel’s attempts to make sense of his experience, likening it to dream analysis as a party trick (p150):

A girl I’d known in Thailand had offered dream analysis to hippies at fifty baht a shot. Most of it boiled down to sex. A chimney meant a prick, a basket a cunt, all extremely formulaic.

Like dreaming when you’re awake

Mental health professionals often normalise hallucinations by referring to them as like dreaming when you’re awake. It’s an interesting analogy as, for some professionals, this would render them meaningless, while for others, it makes them ripe for interpretation. As writers, we get more mileage from hallucinations if we give them meaning.

Although I read a lot of good novels with a mental health team, I don’t find many about psychosis and hallucinations. Playthings is one exception; another is a recent read, Epiphany Jones, mentioned above. As I’m learning how to do this in my current WIP, any pointers to fictional models of which you’re aware would be gratefully received.

If hallucinations are the externalisation of the unconscious, writers can go a step further by severing the link with dreaming and making these projections into characters themselves. Examples can be found in Denis Murphy’s monstrous flatmates in Me, Myself and Them, James Marlowe’s figurines in The Zoo and Alice’s imaginary friend in How to Make a Friend.

A dream is just a dream So to a fresh 99-word story in response to this week’s Carrot Ranch prompt, courtesy of Ruchira Khana. I thought I’d come full circle with Freud’s a cigar is just a cigar, but perhaps that would be a failure of imagination: |

“What does it mean, doctor?” She sat back, wide-eyed, expectant.

Flying cats, talking trains and flowers oozing blood. The ward staff called her an attention-seeking fantasist, but I gave her an hour a week of my full attention and she filled the space with her rambling dreams.

I didn’t want to disappoint her, but none of my interpretations had hit the spot. Sometimes a dream is just a dream. But only in their telling did she seem alive. “I wonder,” I faltered, “did you ever dream of writing a novel?”

She snatched a tissue. At last, we could begin.

For more stories getting underneath Underneath, click on the image below.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed