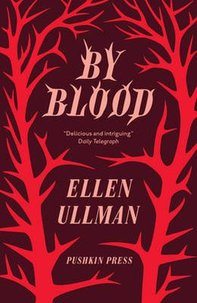

This was one of the most credible fictional accounts of psychotherapy I’ve discovered so far. Alongside the mind-blowing personal discoveries, were the sulks and silences, the tedium, the long hard graft for both patient and therapist in their search for the truth. While some might find the fly-on-the-wall approach introduces an unnecessary distancing from the patient’s narrative, it works well as a way of exploring the process and rituals of therapy. His observations, such as this on the Christmas break:

bring a touch of humour to an otherwise serious novel.

With the scepticism engendered by his own disappointing therapies, the narrator has the right amount of insider knowledge to steer the uninitiated reader through the process. He is alert to the therapist’s limitations in a way that highlights the complexity of the therapeutic task, yet blind to the extent of his personal overidentification with the patient. Experiencing vicarious terror, he leaps into grandiose rescuing mode, failing to appreciate that the therapeutic role is more to bear witness than to intervene:

And finally I could bear no longer the patient’s suffering. I could not stand this death-in-life. She was to be my icon, my champion. And the more mired she became in the muck into which Dr Schussler had shucked her, the more determined I became to save her. She would not abandon her search; the doctor could not guide her. Now only I could help. (p.193)

Despite the narrator’s critical stance towards the therapist, he failed to pick up on a few things that caused me some concern: her apparent desire to hug the patient after a particularly difficult session (p82); her occasional attempts to control the content, including pushing the patient to search for her adoptive mother; her offer of an extra evening session when things got more interesting (p111). And he seemed unaware that therapists should be receiving supervision as routine, and not only for those cases which arouse difficult feelings (the countertransference) as was certainly the case for this therapist when the patient’s story began to reverberate with her own dark history. After finishing the novel, I also began to question the artifice by which the narrator is able to listen in. If you’ve ever had the bad luck to be allocated a hotel room with an adjoining door to another bedroom (albeit a locked door), you’ll appreciate this isn’t the ideal way to put an anxious individual at their ease. I’ve never come across the white noise machine Dr Schussler used to mask the voices of her other patients, but imagine it would be a significant impediment to sharing one’s private thoughts. But if you can set that to one side long enough to read the novel, as I did, it’s certainly an intriguing read, not just about the therapy but about the enigma of identity and how much or how little is bequeathed by our parents.

Thanks to Susan Osborne of A Life in Books for bringing this novel to my attention via Naomi Frisby’s review on The Writes of Woman.

Next in this series I’ll be picking apart The Delivery Room by Sylvia Brownrigg.

Have you read any other novels with a similar fly-on-the-wall narrator? Do you think such a frame would enhance or detract from your appreciation of the central story?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed