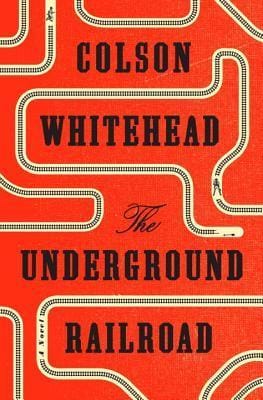

The plantation life of “travesties so routine and familiar [to Cora] that they were a kind of weather, and the ones so imaginative in the monstrousness that the mind refused to accommodate them” is alien to Caesar who, despite being property, has grown up in the more liberal north. He’s set on escape, and determined to take Cora with him. Initially reluctant to risk the torture she’s witnessed meted out to returned captives, Cora agrees. The rest of the novel reads as an adventure story crossed with a history lesson and a scream of rage of the abuse of black people by the white, as Cora journeys through different states, some more benign than others but all denying her people their freedom and autonomy, pursued by the relentless slave catcher Ridgeway.

I didn’t know about the network of safe houses for runaway slaves until I read Tracey Chevalier’s novel, The Last Runaway. Colson Whitehead gives this metaphorical underground railway a physical form as Cora travels along subterranean tracks with no control over whether she’ll be dropped off. The stations, reached by a trapdoor under the floor of isolated houses, are continually under threat of being discovered and their guardians made an example of.

With unflinching descriptions of the most heinous cruelties, along with the white reader’s fear that, had she lived through those times, she might not have risked her own skin to save a fellow human being, this isn’t a comfortable read. Yet the ease of identification with the character of Cora and her quest, the importance of the subject matter and, most of all, prose to die for meant I always looked forward to picking this novel up again. The winner of the National Book Award 2016, The Underground Railroad is published by Fleet to whom I’m indebted for my review copy. If you’ve read this far you’ve probably sparked off some nightmares already, so you’ve nothing to lose and lots to gain by reading this marvellous novel.

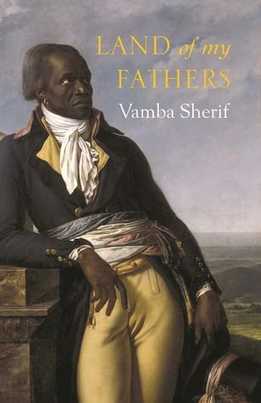

Leaving the capital, Monrovia, Edward sets out on his mission encountering friendly and hostile communities, in one of which he’s disturbed to find men who have sold their fellow Africans into captivity. When he finally finds a place to settle, he forges a friendship with Halay, the son of the mayor, who inducts him into the culture and customs, including the mythical powers of the terrifying masked beings who play an important role in the coming-of-age rituals for adolescent boys. War is always on the horizon but, in contrast to his father, Halay wants neither to lead not to fight. He makes the ultimate sacrifice in the belief that this will rid the threat of war from the land.

Sadly, a century on, one of his descendants, another Halay, is a twelve-year-old refugee from Liberia’s civil war. While his mother tries to establish a new business and his father sinks into depression, Halay eavesdrops on the elders’ discussions about the causes of the war. Was it greed, tribalism, nepotism, the agitating of outsiders or the result of the country’s origins? The boy, however, is more interested in drawing although, like others whose interesting stories are difficult to tell, he finds his (p186-7):

attempts to draw war, to give shape to our terrors and experience … were either detached from my innermost feelings, chaotic or mere fantasies that lacked depth

and, on talking about it to his first girlfriend, feels (p212):

I had betrayed what had held me together by sharing it with someone who had not lived it or could not understand.

Vamba Sherif lives in the Netherlands, but was born in Liberia and has experienced refugee camps from the inside. This, is fifth novel, is published by HopeRoad who provided my review copy, my first from this publisher specialising in writers and writing from and about Africa, Asia and the Caribbean.

I’ve been thinking names this past couple of weeks, having renewed my interest in, and energy for, the project I’ve been calling Closure. It’s a fitting title, in that it’s about a psychiatric hospital closure in 1990 with one of the point of view characters, Henry (who was initially George when he first appeared on Annecdotal in another flash fiction challenge), is looking for emotional closure regarding a sister who’s been missing for fifty years. However, I’m generally suspicious of that concept and, besides, as a title it’s rather dull. A possible alternative is Such Dreadful Lies taken from Hilaire Belloc’s humorous poem, "Matilda", which fits the storyline of another character of the same name, also known as Matty, but I’m wondering if it’s too twee? Fortunately, 30,000 words into my third draft, I’m a long way from needing to confirm my title. But I’m trying it out with my flash, which is about Matty’s troubled relationship with her alter ego.

Matty stared into the picture, holding it so close her breath clouded the glass. She wiped it with the sleeve of her cardigan, but she still did not recognise the woman. But there must have been a connection or they would not have placed the photograph beside her bed.

A voice whispering in her head: Matilda told such dreadful lies … Matty had worked for years to dissociate herself from her mischief. The photograph tumbled from her hands, meeting the floor with a smack. Matilda escaped through the broken glass to ruin Matty’s reputation with deceit.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed