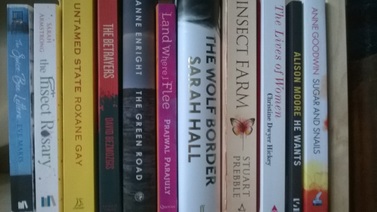

It’s the prospect of the sale of the farm where they spent their idyllic summer holidays that forces Bernie and Nancy to review their memories of Northern Ireland during The Troubles in The Insect Rosary. Similarly, Roseleen Madigan’s announcement that she’s decided to sell the family home summons her children to another part of rural Ireland for one last Christmas in The Green Road. We meet another matriarch in Land Where I Flee, as Chitralekha Nepauney’s Westernised grandchildren return to their Himalayan hometown to mark her landmark eighty-fourth birthday. For Rachel Caine in The Wolf Border, it’s not family that calls her home, but a reforming landowner’s tempting job offer.

There’s often an alliance between the pull of the other and the push within the characters themselves in these homecomings. Even those who profess themselves unable to refuse the demands of a powerful parent, grandparent or aristocrat must have some reason of their own to return. I suspect it’s more than a sense of filial duty that drives Jonathan Maguire to give up his university studies and return home to care for his “special” brother in The Insect Farm. For Elaine in The Lives of Women, the need to reconnect with her sixteen-year-old self is as conscious, albeit confused, as her responsibility to her disabled father. For Sydney in He Wants, there’s no apparent pull back to his hometown; sometimes we go home because there’s nowhere else to go.

My own novel, Sugar and Snails, is about a middle-aged woman’s turbulent adolescence and its ramifications. Having kept her past a secret for thirty years, she’s afraid to go back either in her thoughts or in person, either to Cairo where things came to a crisis or to the mining town where she grew up. Diana left home at fifteen to go to boarding school and, although she has been back since, her family don’t feature prominently in her life. So I knew that a scene in which she visits her parents (ostensibly in order to pick up some documentation) would be an excellent vehicle for exploring the tensions between past and present. In one of my novel’s many incarnations, I made this my opening scene. Now that the novel kicks off with an incident of self-harm, it’s been pushed right back to chapter 27 where, instead of raising questions about Diana’s character, it further elaborates on what’s made her who she is.

Although Diana isn’t particularly insightful, she does at least accept her parents’ limitations. Steve, the narrator of my next novel, Underneath, is even less attuned to his roots. For most of his twenties and thirties, he’s lived abroad, distancing himself from his family of origin. As in a couple of other novels on my homecoming shelf, he’s called back from his travels when his mother’s house is put up for sale. Unable to bridge the gap between his unacknowledged loneliness and his idealised version of homecoming derived from a childhood game with his friend, Jaswinder, he goes to pieces when things go awry with the adult home he’s tried to create.

While I’m drawn to fiction that explores the painful nature of a home that was never a secure base, this review of that theme in my reading and writing has made me want to arrange my ninety-nine words into something more playful:

The key’s under the geranium pot: recklessness in a vulnerable widow; perfect for a son making a surprise visit home. Buzzing with the caffeine that fuelled my overnight drive. Buzzing with the promise of making Mum’s day.

Her snoring filters through her bedroom door. More grunting, rather; a doctor really ought to check that out. A cry, a whimper of pain; why hadn’t she mentioned she was unwell?

Balancing her breakfast tray, I open the door. Two wrinkled bodies disentangle themselves from the bedclothes. Two grey heads rise in horror.

“Oops,” I say, “better go and get another cup.”

Thanks for reading. Are there any homecoming stories you’d recommend?

| Addendum: January 2017 Since a blog bestows on me the virtual superpower of time travel, I’ve decided to add another 99-word story, prompted by Charli, relating to the theme of this post. But how the world has changed in those fifteen months since I wrote about creation myths in fiction. The woman I was then would not recognise half the references that have shaped this flash. I can only hope I don’t have to come back in another year or so with even gloomier references. |

In the beginning, says God, was the Word …

In the beginning, says Bill, was Microsoft.

Ahem, Wordperfect was created long before your Word.

In the beginning, says Donald, is and was the phallus, source of power and pride. And who needs words when 140 characters can express the deepest truths.

Or lies, says Meryl (the overrated actress), and the women in their pussy-hats raise a defiant cheer. Besides, the Creator must be female; it’s She who bears the child.

As a penis substitute, says Sigmund. Born of envy.

Yours or ours? says Anna, as she confiscates his pipe.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed