| In her early twenties, after a gap year that turned into three, all spent under her parents’ roof, her mother had insisted that she go away to university, if she could still find one that would take her. And so she had gone to university, although it was not, as her father had pointed out, a proper university; it was not a good university. She majored in English, because it had always been her best subject and because she had managed to get a B at A level. It was also her native language. |

Alison Moore specialises in deceptively simple stories, tightly written and comically dark, with a highly intelligent and psychologically sophisticated undertow. Her fiction explores the heroism and pathos of unheroic lives, of characters lacking in motivation, and exposes the strangeness behind the ordinary, the magic of the mundane. (When Sylvia suggests the holiday, Bonnie’s ambition is to stay at an identikit Ibis, or a Comfort Inn.) Her two previous novels, Man Booker shortlisted The Lighthouse and He Wants, focused primarily, but not exclusively, on the lives of men, so it was interesting to see where she’d go with a story about the friendship between two women.

The female focus affords the opportunity to explore exploitation within friendship and, somewhat like Pat Barker in Regeneration, drip feed satisfying droplets of feminism, such as a rare moment of self-assertion from Bonnie as she reflects on her degree (p11):

In her first term, in An Introduction to English Literature, she heard about the death of the Author, and at first she wondered who they meant, and then she realised that it was all of them, all the authors, and Bonnie thought fleetingly of the dodo. And what was more, asserted Barthes, the Author enters into his own death, or her own death, thought Bonnie, who had just started writing herself.

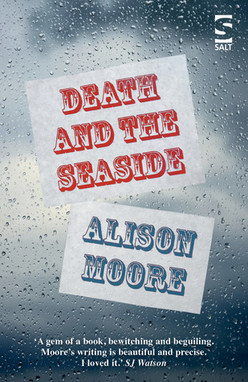

But it would be a mistake to read Death and the Seaside as primarily about friendship, or even particularly about women. For a little while, although enjoying it immensely, I struggled to articulate to myself what it was about. The text is replete with imagery, as Alison Moore’s fiction tends to be, and I trusted that these early references to death, fear, failure and falling would add up to something special. Indeed it does but, while the evidence suggests that spoilers don’t spoil, if you want to discover how for yourself, you can jump ahead to the photos.

I was primed for the psychology, through both my own professional background and a prepublication conversation with the author when I organised a fringe event at the British Psychological Society Annual Conference at Nottingham City of Literature. Skinner’s work on operant conditioning is neatly foreshadowed through Bonnie’s cleaning job (p19):

She wiped the backlit buttons that said things like ‘PRESS’, ’PUSH’, ‘PUSH!’, ‘HOLD’ and ‘GO’, buffing away the build-up fingerprints made by the punters’ fingertips pecking and pecking at the buttons, waiting for the payout.

It turns out that Sylvia is the character with the background in psychology, proving rather overzealous in her attempts to emulate the big names in experimental social psychology (p92):

It was around that time that I had my first run-in with the university, receiving my first warning. In my defence, I cited Milgram, and Watson, and others who had not been hampered by impossible-to-know long-term effects on the subject. All sorts of things which used to be allowed in experimental psychology are unfortunately no longer permitted, formally.

Of course, I can’t say where her passion takes her, but I saw similarities with Stella in my short story "The Experiment Requires".

Like My Name Is Lucy Barton, Death and the Seaside is also a novel about the creative writing and the creative writing industry. I’m sure many writers could identify with Bonnie, waiting for Sylvia to read her story, feeling “a bit like lying down while a doctor inspected her soft insides and she waited for it to hurt.” (p66) Earlier, she struggles to make sense of the easily-recognisable advice for emerging writers (p34):

‘Write the moment you wake up, when you’re in hypnagogic state and can access your subconscious.’ What Bonnie wrote sitting up in bed in the morning, what she netted from her subconscious, always seemed like so much hogwash. Or she made notes as she was falling asleep, and then, when she looked at them again days or weeks or months later, could not understand what on earth it all meant.

While Bonnie is sceptical of relating to fictional characters like real people, the reader is already embroiled in the conceit as the first character we encounter on the page turns out to be the protagonist of Bonnie’s short story.

How could I not love a novel about reading and writing, about the boundary between fact and fiction, and about maverick psychology? Overall, however it’s a novel about semiotics, and the sometimes subliminal messages of symbols is the glue holding it all together. In Bonnie’s story, Susan is puzzled by a piece of paper pushed under the door of her room. Bonnie’s consciousness is assaulted by adverts and graffiti as she goes about her day. Her parents have raised her as if in an experiment on the impact of self-fulfilling prophecies of failure, but it is left to Sylvia to take this to the limit.

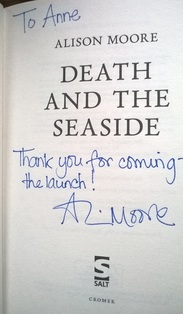

| I haven’t found this an easy review to write because, although a short novel at under 200 pages, it’s packed with nuance, good sense and humour (my first laugh-out-loud moment came sixteen lines in, and was about curtains), and I want to represent it all. But I can’t, so I’ll stop, and suggest you read it. Thanks to Salt for my review copy, Alison Moore for signing it and Dan Norcott for the photo. For other novels about psychology, see my reviews of The Good Children and We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed