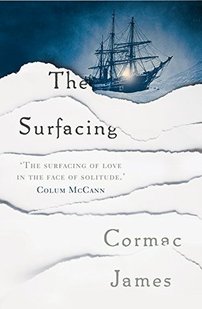

Like Charlotte Rogan’s The Lifeboat and Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North, this is a story of people in extremis, dredging up their last reserves of strength to survive:

He knew this must be their last stop. He could see they were spent, almost. They had courage enough for only one more start. He was almost relieved. There was no more need for heroics, no choice to make. (p170)

Day after day they inched their way down the coast. The fabric was being slowly worn down, worn away. Underneath, through the bare threads, a lone word showed through: Why? He did not know. Out here, no answer could compete. He was earning the right, perhaps to talk about what other men had done. Yet with every destroying day, every hour of drudgery, more and more he felt the breach between himself and them, the men of renown. He had read their books. For them, there had been far horizons, all around. He had gone to the windows they had looked through, and found them walled up. They had been lying, or he was a different sort of man. From where he stood, there was never anything further off than the next step, the next sip of water, the prodigious pains in his legs. (p154-5)

This is a setting in which heroics are entangled with hubris, self-sacrifice indistinguishable from masochism. We witness the loneliness of leadership in a strong hierarchy which can admit no vulnerability, and the absence of comradeship when no man can think beyond his own next step. I was particularly interested in how the elemental danger of the Arctic winter seemed to evoke a kind of recklessness, as if, through suffering, they lose the capacity to value their own lives.

What differentiates Cormac James’ novel from other accounts of polar exploration, is the impact of the female presence. Keeping house for her brother at a whaling station, Kitty takes Morgan, second-in-command of The Impetus, to bed with her when the ship calls in to pick up supplies. Assisted by the clergyman, MacDonald, she stows away on board and, much to Morgan’s embarassment, claims to be pregnant with his child. Kitty has a somewhat civilising effect on the crew and her child a little Messiah in a desperate situation.

This is a beautifully written, multi-layered novel that, despite its somewhat grim subject matter, is a pleasure to read. Having little previous knowledge of the Franklin expedition, I would have welcomed rather more contextualisation of the crew’s quest (which might also have provided another interesting female perspective through the character of Lady Franklin who gets a brief mention on page 282 and seems, like the Ladies of mediaeval times bestowing favours on their Knights, to have shamed the men into setting out to find her husband) to ground me at the beginning. But otherwise a great read, and my thanks to Sandstone Press for my review copy.

My reading of this novel is timely in the context of Charli Mills’ Christmas Eve post which begins with the snow and efforts with an invitation to write a 99-word flash on the subject of visions. While, by sheer serendipity, my previous contribution meets the criteria, I thought I’d have another bash in honour of the brave, or foolhardy, Arctic explorers:

It was days since he’d felt his feet and the midnight glare had left him all but blinded, but still he trudged on. His stomach gurgled incessantly yet meat, when they could catch any, only made them retch. When the cabin boy took his final step they hadn’t the strength to pierce the ice for a Christian burial, but at least he hadn’t ended up on their plates, like the dogs.

On the far horizon sat a ship in full sail. Was it a vision of salvation or a cruel conspiracy of sun and ice, the prelude to death?

In my next post, my 100th and final one for this year, I’ll be looking back at my year in books. I do hope you be able to join me.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed