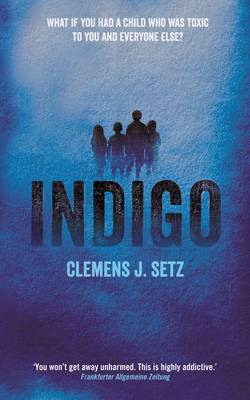

I wasn’t expecting to be disturbed by a futuristic novel about a sinister epidemic of which children are the only carriers, causing anyone who comes near them a barrage of symptoms including dizziness, severe headaches, and nausea. It might not be everyone’s cup of tea, but the darker side of the relationship between old and young, and the devastating impact of parental distance on children’s development, is familiar territory for me, and I looked forward to seeing how this would be explored. The back-cover blurb did nothing to discourage me, but perhaps I ought to have paid more attention to the phrase “part postmodern puzzle”, post-modernism being a concept I’ve consistently failed to understand.

One of the delights of fiction is being able to spend time in the company of people who, in real life, we might avoid. Yet I didn’t encounter a single character in this novel I wanted to get to know better, even in the safety of the page, and the two main characters were decidedly odd, both socially awkward with peculiar phobias and compulsions: Clemens with his red and green files of cuttings of the tales of human cruelty that make him physically ill (which, in that perhaps postmodern way, are interspersed between more conventional* chapters); Robert destroying the matchbox houses built by his girlfriend as an outlet for his anger and depicting the gruesome subjects of animal experimentation in his paintings. That both men had a devoted partner ministering to their vulnerabilities did not make them any more appealing.

*And did I say conventional? Well, that applies only if you consider reporting the detail of banal conversations while obfuscating any context that might enable the reader to feel grounded makes for a conventional novel. Clemens Setz has received numerous prizes for his fiction, so evidently I’m missing something here, but I wouldn’t have thanked him if I’d got a headache in my effort to find it. Perhaps the theme of the novel is to be experienced in the process of reading it. If so, this quote from Clemens’ green folder which appears towards the end of the novel might sum it up (p328):

We’re capable of torturing people if that will make our headache better. … But something’s wrong with us, we’re not quite right in the world. We don’t fit in, nature is of no consequence to us … Our thoughts take strange paths. That results in a great deal of art. … But we would probably even sink a whole continent in the sea just to be a little less lonely.

Indigo was first published in Germany and translated into English by Ross Benjamin. Thanks to Serpent’s Tail for my review copy. For another translated novel from this publisher that I actually enjoyed, see my review of The Winter War. For a more containing account of the human capacity for torture, see In the Orchard, the Swallows. See also my review of Goodhouse for an engaging exploration of the damage perpetrated by institutional “care” systems for troublesome children.

Reading and reviewing Indigo has heightened my awareness of huge difference between readers in what we look for in a novel. Discussing our different reactions has been one of the pleasures of book blogging. I like to think I’m open to experimentation, and steer clear of formulaic reads, I’m drawn to accounts of trauma and the fallibility of human institutions, but I need to be treated gently when I get there. Fine writing, strong characterisation, a glimmer of hope or a writer who doesn’t seem set to give me a hard time can help me through the most challenging topics, but I suppose I have my limits. On the other hand, I’ve also been disturbed by novels treating serious subjects too lightly, as in Hidden Knowledge and Lost and Found, so maybe I’m just an awkward type. What about you?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed