| Marlouw’s sister, Heleen, is worried. When her son, Koert, first went to visit his parents’ homeland in the Bloemfontein region of South Africa, he phoned or emailed almost every day, but now she hasn’t heard from him for weeks, and his last message was mostly gobbledygook. Reluctantly, but not without his own personal agenda, Marlouw agrees to travel from his home in Melbourne to try and find his nephew. Even if it weren’t for his club foot, the journey would be a difficult one in a country where AIDS is rife, the streets are lined with the hungry and desperate, and the infrastructure has collapsed. |

Gradually, Marlouw pieces together Koert’s story. Initially helpful to the Xhosa community on and around the farm, providing them with meat, the young man has become increasingly controlling. By the time his uncle arrives, a gangrenous foot, untreated, has confined him to bed. Despite this, the locals continue to revere and fear him, his reputation compounded by the “witch”, Ooma Zuka. When Marlouw finally meets him, he’s physically and mentally grotesque.

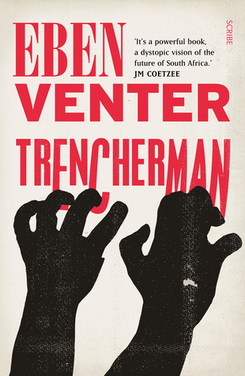

A contemporary retelling of Joseph Conrad’s classic Heart of Darkness, The Trencherman is about colonialism and about returning home in order to leave the past behind. Having loved Eben Venter’s previous novel, Wolf Wolf, selecting it as one of my twelve favourite novels of 2015 and my favourite novel in translation, I had high expectations of The Trencherman. Unfortunately, although I did enjoy it, it didn’t meet those (perhaps overexacting) expectations. A mark of my own ignorance, I’m sure, but I might not have known it depicted a futuristic dystopia where it not for the blurb from JM Coetzee on the front, as the publisher’s blurb makes no mention of this and the “explosion” that might have precipitated the community breakdown is only briefly referenced in the novel. Lost on me too were the references to and parallels with Heart of Darkness since, to my shame, I’ve never read it. (I note that it’s also referenced in Jamie Mollart’s debut, The Zoo, so perhaps I really ought to add it to my TBR shelf.) In addition, the unhurried pace of the opening, which I so admired in Wolf Wolf, here had me mentally urging the author to get a move on. Nevertheless, this is an important addition to South African literature, ably translated from the original Afrikaans by Luke Stubbs and published by Scribe, who provided my review copy.

Given what becomes of Koert, I thought this would be a good novel to pair with my response to the latest Carrot Ranch Flash Fiction prompt to compose a 99-word story on the subject of monsters. I thought I’d find this easy as I’ve published flash fiction about a dinosaur (in a metaphorical sense), a pervert, and a crying baby; and slightly longer stories about an overzealous experimenter, an uncompassionate penpal, and the green-eyed monster, jealousy. My two most recent publications are from the point of view of a man addicted to giving lifts to young female travellers and, as mentioned in my review of Jihadi, a teenager suspicious of the man seated beside her on a plane. Perhaps because the topic was too close to home, and thereby not constraining enough for me, I struggled for inspiration but eventually came up with something (predictably) political:

Perfect Order

His shirts are white; his ties straight and narrow. His words are clear, and in perfect order. He knows what must be done: by him, for us, about them. He, and only he, can save us. If he pauses for even a moment, they’ll pounce: to steal our jobs; threaten our way of life; our very existence.

He reminds us to do our bit, tighten our belts, build fences around our treasures. We must make sacrifices. Can’t you hear them, hammering on the door? The monsters are outside: not in him; not in me; not in you.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed