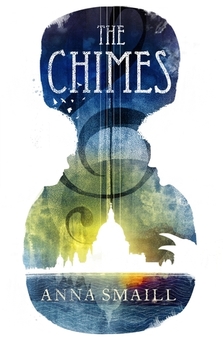

Have you ever been touched by music in a place where words hardly signify? Have you ever been affected by a sound so loud you hear it, not just in your ears, but in your entire being? If your answer to any of these questions is yes – and I’d be surprised if it isn’t – you’ll connect with the themes in Anna Smaill’s exceptional debut novel, but you might need to hold onto these ideas to see you through the disorientating opening chapters.

The plot is a classic quest: two young men gradually uncover the tangle of lies perpetrated by the elite of their country and set off to infiltrate the seat of power and destroy the source of their destitution, risking their lives in the liberation struggle. It’s a straightforward plot, but deployed with sophistication; there’s no simple demarcation between good and bad. Reaching the hallowed halls, Simon, the narrator wonders (p273):

But what did we have to offer her in return, next to this beauty? the voice in my head says. No answers, no order. Nothing but mess, questions, fear.

With curiosity about the past considered “blasphony”, the routines of work are highly valued, contributing to the “bodymemory” that gets the citizens through the day. Personal memories can sometimes be triggered through objects, but the reliance on the physical makes these particularly vulnerable to loss. The more desperate, such as Clare, mark time on their bodies with a knife.

The story begins with a young man, Simon, hitching a ride into London on a horse and cart, his “roughcloth” bag of memories at his side and a tune in his head that he hopes will lead him to someone who will tell him why he’s there. Yet, when he sings out to the market trader, she turns him away. Aimless and alone, he’s rescued by Lucien, the partially-sighted leader of a ragtag group of “mudlarkers” who survive by collecting “mettle” to exchange for food down by the Thames. With a first-person narrator with little sense of who he is and where he came from, the reader is subjected to the same confusion; Maud, the dementia sufferer in Elizabeth is Missing and man of multiple identities and none, Jacob Little in In Search of Solace, are far more lucid guides to the landscapes they inhabit than Simon could ever be. But stick with him and the rewards are great.

Do turn to my Q&A with Anna Smaill to see what she’s come up with in response to my questions about an amnesiac narrator, the novel’s associations to music, religion and psychotherapy, as well as the complexity of pitching a work of such originality and depth. I’ll finish here with a lovely quote reminding us of the value of the written word (p107):

Code was a way of keeping thoughts still. Of helping them stay in formation. Everybody used to understand it, and they could write in it too. It meant that you could return to the ideas when you wanted. Code is a kind of memory.

Thanks to Sceptre Books for my review copy.

Finally a link to my own short story on the power of music, The Invention of Harmony.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed