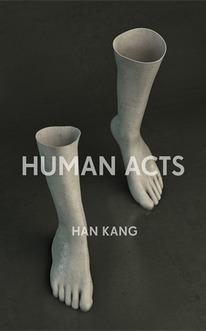

| How does one organise the logistics of identification and disposal of bodies following a massacre? Does the soul exist independent of the body and, if so, at what point might they go their separate ways? How can theatre survive in a climate of censorship? What right has an academic to push a survivor to revisit traumatic memories in the interests of research? What role do women take in agitating for change? |

As you can imagine, Human Acts is not an easy read, but it is an important and thought-provoking one. I was particularly struck by the courage and practicality of the young people, some of them still at school, in devising a system for bereaved reclaim the bodies of their relatives as the death toll mounts. Yet, as I was taken again and again to those terrifying times, I began to distance myself from the narrative. I’m curious, and a little guilty, about my reaction; as regular readers will know, I believe we have a collective responsibility to bear witness to human acts of depravity but, while I don’t believe every cloud has a silver lining, I want my fictional terror tempered by a smidgen of redemption. I might have more to say about this when I’ve reflected on it a little more.

Historically, Human Acts addresses events prior to those in another novel about South Korea, The Defections (whose central character was born in the year before Human Acts begins). Piece by piece, fiction is teaching me about that country. Thanks to Portobello Books for my review copy, my first translation review of the year and my second flagged as ReadDiverse2016.

I’d just started reading this novel (and still thinking it was one I might recommend) when Charli Mills posted her latest flash fiction challenge to compose a 99-word story about rebellion. I had a few posts-in-progress I might have paired this with, but I was pulled to the sociopolitical aspect of the theme. It’s a long way from 1980s South Korea to England in the decade before the Second World War, but it’s made me to take another fictional look at the history of the Peak District with this tribute to the working-class protesters who paved the way to my own right to roam:

| Kinder Mass Trespass, 1932 We came by train and charabanc, in patched tweeds and hobnailed boots. Shouldering canvas knapsacks, we processed up the clough. Lungs exchanging city smog for peat-scented air, we heaved and gasped and sang our defiance to the top. We raised a cheer as, across the plateau, the flat caps of our northern comrades came into view. A grouse cackled a welcome; these moors would not remain a rich man’s playground. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed