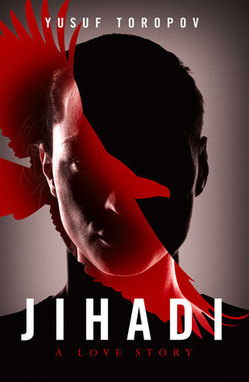

In the current climate of hypersensitivity around interpretations of Islam, Orenda is to be applauded for publishing this novel. (As is the arts magazine Alliterati which has published my short story What time it sunset? in issue 19 this week, about a teenage girl’s initial suspiciousness about the Muslim man in the seat beside her on a plane.)

Around the middle of Jihadi, Liddell’s cellmate explains to him the meaning of Jihad in terms of striving and struggle (p223):

Struggles and obstacles are gifts from our Lord. Even our faults. Even our losses. Even our weaknesses. What is our intention? Whatever we intend to strive for, that is what we worship. Again: Where are we going? What matters is not whether what we attain is just. What matters is whether what we are striving for is just. Whether we make an effort.

I think I knew this, but that concept had been overwritten by the contemporary dominant narrative of Jihad as Holy War. In the novel, Liddell accepts that, on that definition, he is already a Muslim. Perhaps we all are.

I’m not sufficiently knowledgeable about Islam to debate this, but I’m curious about the idea of life as struggle. While consistent with some interpretations of psychoanalysis, it’s highly at odds with the ethos of neo-capitalism which promotes the belief that, not only is happiness our right, it’s something we can buy at the shopping mall. Somewhere in the middle, perhaps, is where we find contentment, which is about not being so wrapped up in what we haven’t got that we fail to appreciate what we have, the topic of Paula Reed Nancarrow's year-long blogging project.

I mentioned recently how I’ve been contemplating my identity as a novelist, but I think the issue I’m actually grappling with is less about who I am how I feel about the writerly effort. I’m struck by how I’ve gone from being ecstatic to have found a publisher for my novel to fretting about sales (that aren’t really so bad given that the odds are balanced so strongly against small presses).

The writing life is built on dreams, perpetuated by the creative writing industry. Hope fuels our ambitions, even if that ambition is one we’ve hardly dared acknowledge even to ourselves. But writing well, and successfully, is a struggle at all stages:

- It’s a struggle to translate the thoughts from our galloping minds into the right kind of words (perhaps especially when those words behave like toddlers and don’t behave as they ought)

- It’s a struggle to secure a publisher for those imperfect words

- It’s a struggle to keep a publisher once we’ve found one

- It’s struggle to talk or write authentically about our published work

- It’s a struggle to find readers for our words

I do think some degree of striving is inevitable, that it’s human nature to push for a little more. As struggles go, writing for publication is a breeze relative to putting oneself in the hands of people traffickers or finding love in an asylum in 1911 and there are deep satisfactions at all levels too. But at each stage we can be shocked at the intensity of the struggle and the effort required for an endeavour with no guarantee of success. For many of us, it’s something we can discover only through experience (as in my novel) of the gap between how things are and how we would like them to be. No matter how much we hear of other writers’ difficulties we, as in Eddi Reader’s song, think we’ll be the exception. I think I’ve reconciled myself to the struggle to convert ideas into sentences, and with finding a platform to publish those words, but I’ve still a lot to learn about the struggle to find readers, despite assiduously following my own marketing advice.

It’s a work in progress for me to find a place between the stupidity of being too busy to celebrate my good fortune and the stupidity of back-pedalling too much on what makes me who I am. I don’t want to be so stupid as to consider myself a failure if I’m not a complete success. I’m sure to update you on my personal jihad periodically, and would love to hear about yours too.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed