Nine years later, Peggy is back with her mother in London, struggling to adapt to a world of overwhelming luxury and choice (p41):

as well as a surprise younger brother. The novel moves back and forth between the two time periods as we discover exactly how Peggy survived in the wilderness retreat and how she made it back to civilisation.

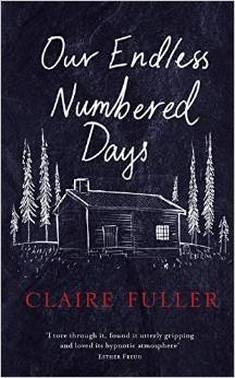

Our Endless Numbered Days is a coming-of-age story with a difference. Peggy’s dependency on an immature man with increasingly questionable parenting skills is played out with psychological acuity. Yet returning to her mother's care as a young woman, she cannot hope to make up for the part of adolescence she’s missed. As her mother looks in vain for the tears she expects following Peggy’s sessions with “Dr Bernadette”, we realise the impossibility for even her closest family of conceptualising what she had to do to survive. I found this aspect reminiscent of the second half of Emma Donoghue’s novel, Room.

While her father is clearly the villain of the piece, the mother isn’t completely exonerated, having withheld important parts of herself from the girl (p114):

The dots, sticks and lines blurring in front of me meant nothing. Ute had never taught me even one note. Sometimes I had been allowed to stand beside her whilst she practised, as long as I didn’t fidget, but I never understood the translation of the cryptic symbols into the jumps and ripples she made with her fingers, and the sound that came out of the piano. Like the German language, Ute had kept the music for herself.

It’s only at the cabin, on a makeshift piano her father has manufactured, comprised of wooden keys that can never produce a tune, that Peggy comes close to appreciating her mother’s passion for music.

For the author’s take on this engrossing debut novel, see my Q&A with Claire Fuller. And if you find the premise appealing, you might also enjoy some other novels I’ve reviewed which address overlapping themes: an intense father-daughter relationship in a post-apocalyptic world in The Ship; the power of music, not only in The Chimes (review coming soon, but you can discover more in my Q&A with Anna Smaill) where this is one of the major themes but also the silent piano playing of Rebecca’s mother in Still Life with Bread Crumbs; a teenage crush in conditions of severe deprivation in The Undesirables; and surviving the cruel winters in The Surfacing and in The Snow Child. Thanks to Fig Tree for my review copy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed