He arrives to heel, an old dog again, half-blind and utterly exhausted, then he folds himself down on the ground and looks at me sideways, as if ashamed of his own frailty. And I find myself wondering which I will be left with in the end, the dog or my father, then try not to think which one I’d prefer.

The enclave of absent men and frustrated women, the suburban homes hide their quiet violence beneath a mask of respectability (p40):

Some detached, some semi-detached. Redbrick to steep roof. Some gardens bigger than others. Apron of lawn front and back; elbows of lawn at the sides of a detached house. A driveway. Square pillars, double gate. A hedge to the front: not so high that the house could hide behind it, but not so low that a child could climb up and hurt itself – or, worse, ruin the line of the hedge.

I come down here to try to cure or maybe kill something, in a hair of a dog sort of way, but all I ever do is remember … Brooding on the past, on the horror of being young: on all the stupidity and ignorance and misplaced loyalty that goes with the territory … I think about what it was like to be living here at that time … About the unimportance of children and the importance of men. I think about the lives of women.

We accompany Elaine on her journey between past and present: her current empty existence with the father who has nothing to say to her; the summer she was almost sixteen, the mothers drinking martinis while Elaine and her friends learn to smoke and ponder adulthood. Gradually she leads us to the horrific event that resulted in her tearful exile.

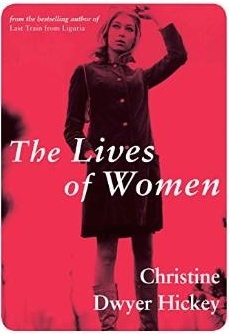

Beautifully written, The Lives of Women is about friendship, keeping up appearances and parental neglect. In the girls’ disdain for their mothers’ lives, which backfires on them, I was reminded of Aria Beth Sloss’ debut, Autobiography of Us. In the all too abrupt coming-of-age (Elaine, in particular, is smothered by her mother until she is rejected) it echoes The Virgins and This Beautiful. Those three novels are set in the US, whereas this is an Irish novel that wears its Irishness lightly (if that sentence sounds odd, it’s perhaps because I’m writing this review on the heels of a new breed of Irish novel, The Glorious Heresies incidently published in the UK on the same day). Our relationships with neighbours is also the theme of another of my recent reviews, this time across the other side of the globe in Australia with Tim Winton’s Eyrie.

This is a novel that resonates strongly for me, not just for the echoes with my reading, but because of the parallels I see with my own forthcoming debut, Sugar and Snails, summed up for me in the first chapter when Elaine looks back on her younger self (p13):

There is something about her, a certain expression – what it is, I couldn’t say.

I have this overwhelming need to understand her anyhow; to know who she is or why she is here. To know her story. To forgive it, even, if that’s what it should come to.

But how do you tell the story of yourself as you were more than thirty years ago? How do you know what you were like then? The workings of your troubled mind and heart. How do you begin to resolve all that?

I wish I’d written that! Thanks to Atlantic Books for my review copy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed