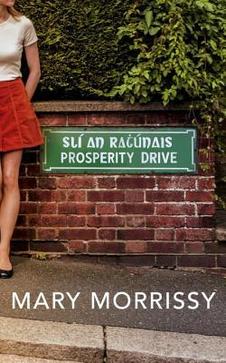

| Edel Elworthy is confused about most things, but she’s pretty sure that her adult daughter, Norah, who has moved back into her childhood home on Prosperity Drive to care for her, is aware that she’s fallen at the top of the stairs. But she “thinks she understands why lately Norah has refused to come running. Payback” (p4). Though there’s something she feels she ought to tell her if only she could form the words. |

Between these bookends we are plunged deep into the lives of not only the Elworthy family but their various neighbours from the middle-class suburb. Rather like the stories of Alice Munro, any one of these eighteen stories has enough substance for a novel, told with great economy and glittering prose. Each works as a stand-alone story while together adding up to, for me, less an impression of a particular place, but of the intricacy of human relationships.

Moving around in time, we meet the child behind the adult, often seeing the experiences that have shaped them of which the characters themselves are unaware. While the broad cast of characters can be confusing (I’d often start a new story asking myself whether I’ve met this character before), the slight irritation this induces is outweighed by the pleasure of encountering a familiar figure from another angle. There’s a parallel process between the reader’s sense of dislocation (not something I’d normally relish) and the overall theme of connection and disconnection: how figures from our pasts might stay in our minds, even if our relationship to them was slight; how we can feel alienated from those with whom our lives are more clearly intertwined.

Like My Name Is Lucy Barton and Hot Milk it’s particularly strong on the complexity of mother-daughter relationships, but my favourite was the story of the fierce adult literacy teacher making amends for a childhood betrayal. Perhaps because of the setting in Catholic Ireland, the theme of guilt and reparation is beautifully handled. The book as a whole makes me think of how the sacrament of confession might be, if it could be divorced from the need to appease an omnipotent supernatural being and from the hypocrisy of the established church; a setting out of ordinary human failings in a spirit of, if not quite forgiveness, at least compassion and acceptance that none of us are as good as we’d hope to be.

Despite the profundity of its approach, Prosperity Drive is not without humour, such as in this glimpse of Norah’s brief marriage (p197-8):

Louis had boasted to friends that he wouldn’t have a rolling pin in the house because theirs wasn’t that kind of marriage. Which meant that Norah had to use a milk bottle; for baking, that is. All her piecrusts had the letters MBL imprinted on them. Sometimes, faint vestiges of the warning on the bottles would also appear before the tart went into the oven: Must Not Be Used Without Permission.

In both language and sentiment, a beautiful book, regardless of whether it’s best described as a novel or a collection of short stories. Thanks to Jonathan Cape for my review copy and for introducing me to an author whose backlist I’m keen to pursue.

For my virtual annethology of Irish fiction, see also my St Patrick’s Day post from earlier this year.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed