The novel begins with Patricia reviewing her life. Nearing ninety and resident in a care home, she is often described by the staff as “very confused”. But her confusion has an extra layer to the usual fictional dementia: she has vivid memories of two separate selves with two distinct sets of children.

Both threads begin with a little girl called Patsy, playing on the beach with her father and brother. They also include Patty evacuated with her school at the outbreak of the Second World War which kills both her father and brother. Patty makes it to Oxford University where she almost crosses paths with Wittgenstein and Alan Turing and, only a few days before graduation, falls for the somewhat intense Mark. After a two-year separation and countless passionate letters, Mark phones her to ask her, somewhat hopelessly, to marry him.

But somewhere around the late 70s their trajectories change. Tricia (now Trish) divorces Mark, becomes active in the women’s movement, local politics and her re-ignited teaching career. Pat suffers a family crisis. But despite periodic forgetfulness, Pat is soon blissfully happy once more, while Trish gives up her own ambitions to care for others.

Time has been marked in both threads by snippets of global news (such as the Kennedy assassination; moon landings; and the Cuban missile crisis) which I dismissed as an irritating distraction from the human narrative until it dawned on me that they were straying from the facts (e.g. Prince Charles marries Camilla instead of Diana; United Europe is more powerful than the USA). But this external context strains credibility when Trish gets her first computer around the time her younger son gets married on the moon. Around the same time, a pregnant Pat is concerned about the fallout from nuclear bombs on Miami and Delhi. Meanwhile, the seven children are coupling and reproducing with a profusion of character names that left me as confused as Patricia.

When Patricia’s two halves are reunited in the Lancaster nursing home, it seemed that the message of the novel was that, wherever life takes us, most end in the same place with worn out bodies and/or minds. But the old woman’s musing on the butterfly effect suggested something more grand or, indeed, a grandiose delusion in her speculation that her response to Mark’s proposal had shaped the future of the world. Yet Patricia’s sense of omnipotence goes further: Trish’s self-sacrifice has brought world peace and prosperity while Pat’s decision to be true to herself has inadvertently brought about a nuclear war.

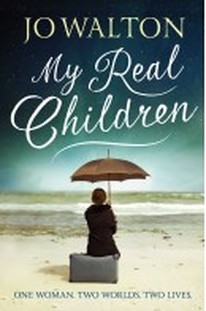

As Jo Walton is a writer of science fiction and fantasy, perhaps I ought to have anticipated such a preposterous conclusion. I might have been more inclined to swallow it had the parallels between the two lives been sharper, or their intersections more significant, and relayed through less pedestrian prose. There’s a lot of attention to detail in the novel but, unfortunately, not the type of details that might have helped me appreciate this novel better.

Nevertheless, an interesting premise. Thanks to Corsair for my review copy.

Do you ever look back at a decision point in your life and wonder how things would have been had you gone for a different option? It must be a subject that haunts me, as it’s one of the themes of my forthcoming novel, Sugar and Snails. Yet it’s the events that were not of my choosing that have had the biggest impact on my own life. Nevertheless, I do wonder if I’d still be stuck working in a bank in my home town had I chosen to leave school at sixteen rather than stay on for the A-levels that would get university. And I still struggle with muddled priorities, one of the themes of Charli Mills’ flash fiction challenges earlier this year. How about you?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed